In the ancient world art and monuments were used by kings and rulers as a tool to control their subjects. Art was intended to reinforce the status of leaders and present them in a powerful light. People were largely illiterate, and images, particularly permanent ones carved from stone, were very effective vehicles for promoting official ideology. A famous example of the skillful manipulation of public opinion through official art is that made by the pharaoh Ramses II after his very questionable victory at the Battle of Kadesh.

Ramses II was born in 1303 BCE and is believed to have been the Egyptian pharaoh in power at the time of the Biblical Exodus of the Israelites under Moses (Figure 1). He was the son of the great pharaoh Seti the First.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

Five years into his rule, primarily to extend Egyptian control over the area we know today as the Middle East, but also to establish himself as a match in military prowess with his father, Rameses launched an attack on Kadesh, a hill-top town in modern Syria, which was under the control of the Hittite king Muwatalli. Rameses believed that conquering Kadesh was crucial to controlling the trade routes of the Middle East. The Hittite Empire was a powerful country to the north, in modern day Turkey, which Egypt had been in conflict with in previous times.

In May 1274 BCE, Rameses set off from Egypt with an army of four divisions which he named after Egyptian gods: Amun, which he took control of himself, Re, Seth and Ptah. It is estimated that there would have been approximately 5,000 soldiers, including 500 charioteers, in each division, an army of around 20,000 soldiers.

Rameses was so eager to engage with the Hittites, and so confident of defeating them, that he unwisely allowed his Amun division to advance ahead of his other forces. After a month’s march, when he was about 11 kilometers south of Kadesh, Rameses scouts brought two nomads to him who assured him that the Hittites were hiding “in the land of Aleppo” some 200 kilometers away, and that they were too afraid to meet the Egyptians in battle. This lead Rameses to believe that he had a strategic advantage and that he should press his attack without waiting for his other divisions to arrive.

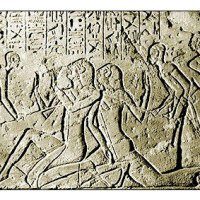

But soon after, his scouts brought him two captured Hittite soldiers (Figure 2), who when beaten severely revealed that the Hittite army, with infantry and chariots numbering 40,000 was in fact lying in wait behind the hill of Kadesh.

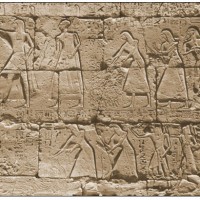

Rameses now realized he was in a dangerous predicament. His other divisions were still many kilometers to the rear. He sent word back that they should increase speed, but the Hittites had already made moves to cut the Amun division off by attacking the Re division. Re was almost completely destroyed. The Hittites then swung around to attack Amun from the rear. In the ensuing battle, (Figure 3 ) Rameses recounted that he was deserted by his soldiers, who flew in panic, and became surrounded by his enemies. Wall inscriptions claiming to quote Rameses assert: “No officer was with me, no charioteer, no soldier of the army, no shield bearer…”

And yet, with the help of the gods (and some much needed relief from the remaining divisions) Rameses managed to valiantly beat the Hittites off and drive them back to the safety of Kadesh, although many had to abandon their chariots and swim the Orontes River “as fast as crocodiles swimming” to escape.

After another inconclusive battle the following day a truce between the Hittites and Egyptians was called. The Hittites remained inside the walls of Kadesh and Rameses realised he was in no position to lay siege to the town for an indefinite period. Rameses returned to Egypt, where he proclaimed that he had won a great victory. The amputated hands of thousands of the Hittite enemy were laid at his feet in tribute (Figure 4).

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

However, in spite of Rameses’ personal bravery on the battlefield the result of the fight had actually been at best a stalemate and at worst almost a catastrophe.

Relief sculptures, monuments and hieroglyphic inscriptions were chiseled onto temples throughout Egypt extolling the victory and Rameses decisive part in it. For example, on the temples walls at Luxor is the following inscription:

“His majesty slaughtered the armed forces of the Hittites in their entirety, their great rulers and all their brothers … their infantry and chariot troops fell prostrate, one on top of the other. His majesty killed them … and they lay stretched out in front of their horses. But his majesty was alone, nobody accompanied him…”

The Hittite record of the battle, discovered in the town of Boghazkoy, in present day Turkey, and once the site of the Hittite city of Hattusa, tells a very different story. From their perspective, Rameses had had to withdraw from Kadesh in humiliating defeat.

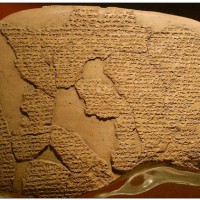

Over the next fifteen years a series of border skirmishes erupted between the two empires, with neither achieving any decisive victories. Eventually a peace treaty was negotiated and entered into. The agreement, inscribed on a silver tablet of which a clay copy is stored in the Istanbul Archeology Museum, (Figure 5) is thought to be the first recorded international agreement of any kind. An enlarged copy of it hangs on a wall in the head quarters of the United Nations in New York.

The mythologising and promotion of Rameses heroism in artworks on the walls of temples throughout the land tells us a much about the role of military artworks in ancient Egypt. The pharaoh controlled the production of art and tuned it to serve his own ends. The Egyptians believed that whatever was represented in stone was real, permanent and true.

Seeing the same incidents portrayed over and over in temples across Egypt not only reinforced the official version of the battle and convinced the pharoah’s subjects of his greatness and invincibility in battle, it confirmed for them the immutable truth of the events through the permanence of the stone medium the scenes were carved from.

The town of Kadesh itself was destroyed by invading Sea Peoples in 1178 BC. While there are still people living on the hill summit all evidence of the township has disappeared other than a few ruins and potshards (Figure 6).