“If I were king the worst punishment I could inflict on my enemies would be to banish them to the Solomons. On second thought, king or no king, I don’t think I’d have the heart to do it.” – from “South Sea Tales” by Jack London (1911)

“Life in the Solomons is hard.” – Stanley Auger, Honiara taxi driver (2010)

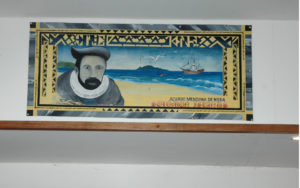

The Solomon Islands, named after King Solomon in the unfounded belief that the islands were rich with gold, were “discovered” and named by Spanish explorer Alvaro de Mendana de Neira (Figure 1) in 1568, sailing from Peru. The islands were taken possession of in the name of the Spanish king. They named Guadalcanal after a village in Spain.

Mendana returned 28 years later in1595, intending to become the governor of the Solomons. The settlement the Spanish created at Graciosa Bay in the Santa Cruz Islands (North of present day Vanuatu) was a disaster, with fighting amongst the Spanish as well as with the natives. Mendana died in October of that year, and when the remaining survivors set sail for Manila a month later they took Mendana’s body with them. Unfortunately the ship with Mendana’s body on board disappeared at sea.

Guadalcanal was a pivot-point in the War in the Pacific. The Solomons represented the furthest expansion of the Japanese Empire and was crucial to Japanese plans to interrupt the supply routes between the American West Coast and Australia. On 7 August 1942 the United States Marine Corps invaded the island, overrunning the newly constructed airfield and driving Japanese troops into the hills. The Japanese staged several attempts to recapture the island but were eventually forced to withdraw their forces. Today, evidence of the war is everywhere: signs, most of which are very neglected, recording historic sites (Figure 3), recycled materials (Figure 4), piles of rusting military hardware (Figure 5). An area at the north end of Henderson Field is cordoned off by a high wire fence because it is a dump for still lethal WW2 ammunition.

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 18

Most of the people I met during my ten days in Guadalcanal were friendly and welcoming: the more so the further away from Honiara I went it seemed. The children were beautiful with wide smiles and gleaming white teeth (Figure 6 – 8).

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

When I visited Guadalcanal in 2010, RAMSI (Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands), a coalition of armed forces of Pacific nations, including New Zealand, which was sent to maintain order in the country, was maintaining a level of peace and stability (Figure 9). The program was also known as “Operation Helpem Fren”, which means “help a friend” in Pidgin English. RAMSI was terminated in 2017 and since then the levels of tension and unrest have reportedly increased again.

I left Guadalcanal after ten days on a commercial flight back to New Zealand via Brisbane. Stanley drove me to the airport, with a detour to the open-air museum at Betti-Karma school on the way and a quick visit to his home, like so many houses in Guadalcanal, still under piecemeal construction (Figure 10), where I met his wife and family and we exchanged gifts. I was sad to say good-bye to Stanley and I told him I hoped we would meet again.

I was glad I had made the trip to Guadalcanal, but I was also glad to leave. The oppressive heat and dust, the menacing surliness of many of the people in Honiara and the generally tense political/tribal atmosphere took its toll. In my trips with Stanley, it seemed that the further we drove away from Honiara, the friendlier the people became and the more beautiful the island was.

In spite of the natural beauty of the island and in spite of my prior knowledge of the political tensions on Guadalcanal, I was shocked at the Third World conditions I saw and the animosity toward foreigners that I frequently sensed in the township.

I had many motivations for visiting Guadalcanal. From a historical perspective, I wanted to experience first hand this place that was pivotal to the Allied effort to turn the War in the Pacific against the Japanese. I also wanted to visit the sites and places that some of the artworks that I was familiar with through my research were created, and gain a feeling for the locations and conditions that had contributed to the production of New Zealand soldier art in the Pacific.

And I wanted to visit the island that my father had been sent to as a young man of twenty-three in World War 2, to stand in some of the places he had stood and in a way relive some of the experiences he recounted in his diaries, yet never spoke about, to gain a deeper understanding of the man he was.

On a personal level, this was perhaps the most valuable outcome of my trip to Guadalcanal, and the experience has motivated me to complete the retracing of his journey with a visit to Mono and Stirling Islands in the Western Solomons, where Harry Stone was stationed for nine months.