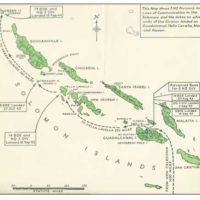

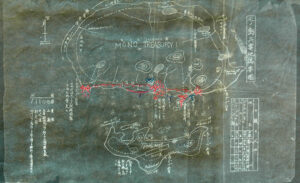

Harry was on Guadalcanal for just over a month. There were two Brigades in the 3rd New Zealand Division, the 14th and the 8th. The map in Figure 1 tracks the movements of the two brigades as they advanced northwestward, with American support, along the Solomon Island chain and onward to Vella Lavella, The Treasury Islands and Green (Nissan) Island.

- Figure 1

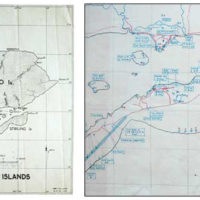

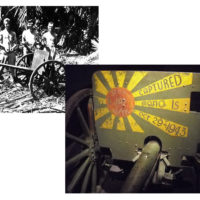

- Figure 2

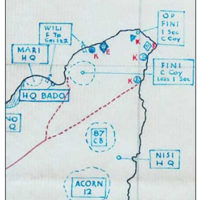

- Figure 3

On 28 October the 8th Brigade left Guadalcanal for the Treasury Islands at the western end of the Solomon Chain (Figures 1 and 2). There is a gap of a week during the invasion of the Treasury Islands before Dad is able to update his diary. He arrived at Mono Island the day after the main invasion, on 1 November 1943.

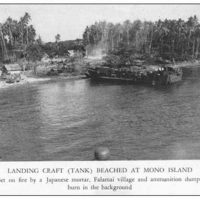

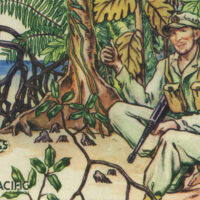

The New Zealand invasion was codenamed “Operation Goodtime” and involved 4,608 New Zealanders and 1,966 Americans. It was the first opposed landing by New Zealand forces (Figures 4 – 6) since the Gallipoli Invasion in 1915. During the assault, 40 Kiwi soldiers were killed and 145 wounded. There were somewhere between 100 and 250 Japanese on Mono, the main island. Those not killed in the fighting fled northward hoping to be taken off the island but were trapped by a pincer operation by New Zealand troops and eliminated.

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

“SATURDAY 4TH. DECEMBER: We learned today of a P.T. boat picking up a canoe containing two Japs who were attempting to escape to Shortland Island. The P.T. boat threw them a rope, but the Japs refused to take it or to attempt to help get themselves on to the boat, so the Yanks opened up with their machine guns.”

According to a photograph annotated “my ship” by my father, LST (Landing Ship Tank) 485 seen in photos unloading on either Mono Island or Stirling Island, was the vessel he arrived at Mono Island on. This is the boat that Russell Clark was later to depict in his painting “Landing Ship Under Fire”.

However, my research shows that Dad could not have been on board LST 485: the LST ships involved in the initial invasion of the islands on 27 October 1943 were LST 485 and LST 399. The official Beach Planner in Figure 7 shows the position on Kukum Beach of LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry) as preparations were being made for the First Echelon of invasion of the Treasury Islands on 27 October. The photograph in Figure 8 gives an idea of what the beach must have looked like as the preparation for the invasion were being made.

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

Harry was part of the Second Echelon. Unfortunately, establishing which ship Harry was actually on is not easy. The two LSTs involved with the Second Echelon were LST 71 and LST 460. The official 54th. Anti-Tank Battery diary records that ‘F’ Troop, Harry’s company, “loaded there (sic) Guns, Amn (ammunition) and Equipment on LST 460” on 30 October. At 13.15 (1.15 pm) “Lieut. Buist, ‘F’ Troop, Lieut. Steer and 9 O/R (Other Ranks) embarked on LST 460” from Kukum Beach in Guadalcanal. The official record therefore indicates that Harry must have been on LST 460.

According to the Anti-Tank Battery Diary official record, on 1 November “30 O/R’s of F Troop” were transported to the Treasury’s on LST 460, and it came ashore at “Purple One” beach on Stirling Island.

However, Dad states in his Diary that he came into “Orange Beach” on Mono Island and was subsequently transferred to Stirling. He refers to two LST craft landing during the invasion, but without giving their identity numbers: “Then came the job of unloading the boat, one L.S.T. went to each island, one to Mono Island and one to Stirling Island…Ours went to Mono Island.”

His account is backed up in “The Gunners: an Intimate Record of Units of the 3rd New Zealand Divisional Artillery in the Pacific from 1940 until 1945” written by J.A. Evans and published soon after the war by Reeds New Zealand:

“On the 30th the first echelon (sic: Second Echelon) party with F troop embarked on LST 71 at Kukum Beach for the move to the Treasuries. They arrived in Blanche Harbour on the morning of 2 November (1 November according to the official diary) and were transhipped immediately to Stirling Island.” This suggests that ‘F’ Troop landed at Falamai on Mono Island first, then were “transhipped” to Stirling Island.

If my father landed at Mono Island then he must have been on LST 71 (Figure 9), on 1 November 1943. This ship was to be involved in the invasion of Okinawa in April 1945 and was decommissioned on 25 March 1946.

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

But if he arrived at Purple Beach, Stirling Island, he must have been on LST 460 (Figure 10). This ship was to be lost to enemy action on 21 December 1944, off Mindoro, Philippines.

Frustratingly, this contradiction seemingly cannot be resolved. While it is admittedly of little consequence in the bigger picture of the War in the Pacific, it suggests that despite best intentions, sometimes individuals get historical details wrong and that the truth consequently can become a slippery road. And, as discussed in the website section on Russell Clark, his painting of the unloading of LST 485 is itself a misrepresentation of the invasion, a synthesis derived from photographs taken at the time.

The following YouTube link gives an idea of what the scene at Kukum Beach must have been like as the loading took place for the invasion of the Green Islands in February 1944:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=maPyHAAQWdQ

The Allies’ objective for securing the two main islands, Mono and Stirling, was to establish an American radar station on the former and airstrip on the latter. This was to accommodate fighter-planes and medium weight bombers of the American 13th Air Force for attacking the Japanese on Rabaul Island to the north. The airstrip was constructed by the 87th Seabees beginning on 29 November and working night and day. It was operational in the first week of January 1944 (Figure 8).

Dad was part of the 8th Brigade Second Echelon, arriving at Mono on November 1. He points out that he was “spared the horrors of jungle fighting”, being in the artillery rather than the infantry, and arriving several days after the main action. His team was ordered to load the dead and wounded onto his truck and take them back to the now-empty LST for evacuation.

Soon after the initial landing on Mono Island, ‘F’ Troop was transferred to Wilson Point next to Lakemba Cove at the eastern end of Stirling Island. Dad’s anti-tank gun was manhandled up a small cliff into position overlooking the channel between the two islands. The exact position is shown on the map in Figure 11, where the position is recorded as “F Tp Gns 1 and 2”. He has marked the position of his gun with an X in the aerial photograph of Stirling Island from his copy of the book “Guadalcanal to Nissan: With the Third New Zealand Division through the Solomons”, the cover of which is shown in Figure 12. Harry was on Gun No. 1, which from this map would appear to have been the gun on the right side of Lakemba Cove.

- Figure 11

- Figure 19

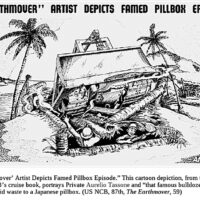

While on Mono Island he saw the aftermath of the famous bulldozer attack by Sea Bee Aurelio Tassone, who drove his machine over a Japanese machine-gun nest on the Falamai beach using his blade as a shield and killing twelve Japanese soldiers : “We visited the place where the Jap pillbox was scooped up by the bulldozer – it had been cleaned out yesterday – a sickly stench hung around everywhere. I saw a Jap boot – half the leg still in it. A Yank soldier took a Jap tin hat down to the water’s edge and washed the head out of it.” (Figures 13 and 14) New Zealand artist Raymond Starr produced a drawing of the action (refer to the section about Starr on this website).

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

During the invasion of Mono Island, a Japanese anti-tank gun was captured by the New Zealand 8th Brigade soldiers, which was subsequently left in the care of Dad’s mates in G Troop. This weapon was subsequently painted with the Japanese rising sun motif by Alan Barnes-Graham and is now in the collection of the Auckland Museum (Figure 15).

Japanese raids on Stirling and Mono Islands continued throughout November, December, January and into February, on an almost nightly basis. Figure 16 shows a captured Japanese map of the two islands, perhaps used by one of the bomber pilots who attacked Stirling.

The airstrip on Stirling was an obvious target for the Japanese, with bombs frequently dropping uncomfortably close to Dad’s campsite. The Japanese objective seems to have been to inflict as much damage as they could but also to harass the invaders and make life as physically and psychologically stressful for them as possible. The men spent many nights sheltering in their foxholes, their faces pressed into the dirt.

“THURSDAY 2nd DECEMBER: Jap planes came over last night about 9.30 – evidently seaplanes from Shortland Islands – our Ack-Ack put up the best display I have ever seen – we climbed under our heavily timbered floor as protection from Ack-Ack splinters, but though we heard them falling in the trees none fell near. The P.T. boats put to sea and we heard a stick of bombs falling close to them after they had passed our point.

“TUESDAY 7th DECEMBER: Today is America’s anniversary of entering the war – “Remember Pearl Harbour!” Perhaps Tojo will put on a first-class show for us tonight.

“WEDNESDAY 8th DECEMBER: True to expectations Tojo put on a first-class raid for our benefit last night. About 9.30 the siren went and the AA went into action almost immediately throwing everything they had at the planes. We can’t ever tell here how many planes are coming over (because of the jungle canopy), but several nights ago the radar boys told us there were sixteen. Two bombs (as far as we could make out) fell on Mono Island but (behind) Falamai where they’d cause little damage.”

“THURSDAY 13th JANUARY: Last night we experienced the biggest air-raid yet – we only went to sleep for an hour at two different times. The first raid started at 9.30 pm and the A.A. fire lasted about an hour and a half, then we got back to bed until 1 am – the start of raid No. 2. This raid lasted about an hour – first three bombs exploded off our point here, then we heard the whine of two coming straight down – it sure makes your hair stand on end when you hear them so close. Those two landed on the U.S.N. C.B.’s camp just behind us, killing five men and wounding forty.”

He once described to me how many of the soldiers would rush to pick up shards of shrapnel from the bombs as souvenirs, only to immediately drop them when they burned their hands.

In the weeks before Christmas 1943 the New Zealand troops were issued with government-produced Christmas cards to send home to family and friends. The design was based on a painting by official war artist Alan Barns-Graham (Figure 17). It was not popular in the Treasury Islands because the soldier depicted in it was wearing an American uniform:

“MONDAY 13th DECEMBER 1943: Our Xmas cards came this morning – they don’t seem to please the boys too much – they show a New Zealander in a Yankee uniform not N.Z. – of course the 14th. Brigade boys on Vella Lavella wear Yank outfits, but why didn’t they show a real N.Z. uniform such as our brigade were issued with?”

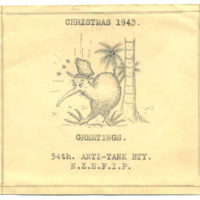

On the same day, Dad recorded that he had turned his hand to producing an alternative design to the official one, delicately drawn in pencil (Figure 18). His design proved popular among his mates:

“I have been drawing Xmas cards of my own design for the boys most of the day – I’ve done eight today – which makes fifteen in all.”

He did not indicate whether he was paid for the cards or whether he traded them for his beloved chocolate.

As the weeks went by and Japanese attacks became less frequent and inflicted less damage, it became increasingly important to keep the men active and engaged. They were able to relax more and use free time for visiting friends in other units, reading books and months old magazines and newspapers sent from Home, swimming, making boats and canoes, drawing and making trench art. Outdoor movie theatres were established, much to Dad’s delight. Exhibitions, concerts and gala days were organised on the main island. As early as Boxing Day a regatta had been organised on Blanche Harbour (Figure 19).

- Figure 17

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

“SUNDAY 26th DECEMBER: There was a “regatta” on today – the motor torpedo boats put on a bit of a display. Also a race for outrigger canoes…There were even three or four yachts sailing about the harbour, they wouldn’t win any design awards, but with hulls made out of box-wood and any timber that could be scrounged, sails made out of parachute cloth, they were a credit to their builders.”

Making canoes was a popular pastime amongst the men. The gunners in Dad’s troop made one out of a heavy mahogany log, only to watch it sink to the bottom when it was launched. It is possible that the watercolour by Oscar Kendall – whose captions on other work indicates that he was in the Treasuries at the time – records the making of this very canoe (Figure 19).

“SATURDAY 15th JANUARY 1944: The boys launched their mahogany canoe this afternoon – it nearly broke their hearts – she crash-dived to the bottom like a sub – but of course there is a bit to be done on her yet. They had to go to the Sea-Bee camp and find someone who is good enough to dive and put a line on it, so it could be retrieved.”

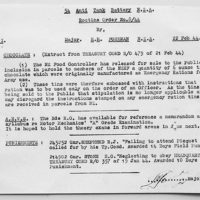

We might well wonder where the men obtained the parachute material used to make the sails for their boats. In the 54th’s War Diary in Wellington I found the following directive, Routine Order 3/44, signed off by Major Foreman (“Bruiser”), about chronic pilfering amongst New Zealand soldiers:

“1. On 15th Jan. 44 three NZ soldiers were responsible for pilfering a US Aerial Parachute Cluster Bomb at Purple 1 and later cutting the parachute from the Bomb.

2. The soldiers were lucky not to have been killed through their foolish action.

3. Anyone knowing of the incident or whereabouts of stolen equipment will report to “BHQ” (Brigade Headquarters) forthwith.”

On 18 December Dad had been admitted to the Brigade Hospital on Mono Island suffering from a badly infected toe. While this may seem a relatively trivial wartime complaint to us, tropical infections were treated very seriously because of the potential for any open wound getting much worse in the heat and humidity. He was to spend Christmas 1943 in the brigade hospital having part of his big toenail removed resulting in regular treatment with disinfectants (antibiotics were still rare: Dad reported that a man on Number 2 gun had died from double pneumonia waiting for the new “miracle drug” penicillin to be flown up from Guadalcanal) and changes of dressing.

He was to miss out on Christmas dinner with his mates, in spite of having somehow found the time to create a pencil-drawn design for the menu (Figure 20), in which it is recorded that “a latrinograph was received from Harry Stone in Hospital regretting his inability to attend owing to a slight indisposition.” The cover drawing shows an inebriated Kiwi resting under a coconut tree after the Christmas feast. The card attached to the roast chicken reads “Love from Peter”, a reference to the New Zealand Prime Minister, Peter Fraser.

- Figure 19

- Figure 20

- Figure 21

Dad was sent back to his unit on Stirling Island in the 1944 New Year:

“TUESDAY 4th JANUARY: Arrived out at the gun this morning and was very pleased to be able to get settled in. I was rather knocked back to learn that the boys here drank all my issue of beer (5 bottles) as well as ate my candy chocolate and tins of fruit for a New Year’s party. They have kindly offered to pay me for the beer. I had intended to swap all my beer for Yankee clothes but circumstances have changed things slightly.”

Dad claims to have initiated the “craze…for making model aeroplanes” from used or “deloused” ammunition cartridges and artillery shells amongst the men. But on Friday 10 February Harry had “a bit of a catastrophe.” The primer cap of a .50 calibre cartridge he was delousing with a hammer and nail exploded and a small piece of metal struck one of his mates, Gunner Allan Boon, in the shoulder. It made a hole “as big as a wart and about as deep” and Harry brushed the incident off. He told the victim that his name would appear in the “Kiwis Wounded in Action” column of the “Kiwi News”.

The authorities took the matter very seriously however and my father was put on a charge. There was talk of a court-martial, since he was in possession of an ammunition round which had not been issued to him. (This type of ammunition is used in aircraft machineguns: it is likely that he was given it by one of his American friends at the airstrip.)

“WEDNESDAY 16th FEBRUARY: This morning the boss showed me a piece in a memo he had just received from B.H.Q. It ran ‘Is there any reason why Gunner Stone should not be court-martialed as the .50 round was obviously stolen by him!’ I was so disgusted I asked if I could have the piece of paper as a souvenir, but the boss didn’t think that funny.”

He wasn’t court-martialed, but he was disciplined:

“THURSDAY 17th FEBRUARY: Today I was “matted” for negligence, resulting in an injury to Gunner Boon and for having a .50 calibre round which was not on issue in my possession. I went over to the B.H.Q. about 11 am. being under the impression that I was just required to give an interview, but I found out different. “Bruiser” held the mat and awarded me 10 days field punishment which I am to spend over at B.H.Q. working.”

While researching the 54th. Anti-Tank Battery Diary at New Zealand Archives in Wellington I found a copy of the disciplinary action (Figure 21).

Dad was extremely bitter about receiving field punishment, although it turned out to be not especially onerous: “At the moment I would not credit any man with having more hate for the N.Z. Army and certain officers in this unit, than I have.” A large part of his resentment sprung from the fact that he was punished “In spite of the fact that at the moment an exhibition of arts and crafts is on at Falamai which encourages men to make things out of cartridge cases and rounds.”

Indeed, also amongst the 54th. Anti-Tank Battery archives, I discovered the following announcement in Routine Order 3/44 on 21 January 1944, signed off by Major Foreman:

“EXHIBITION OF CRAFT:

An exhibition of craft open to all NZ units, 198 CA (AA) Regt. and US Naval Base will be held in the third week of February.

The work will be exhibited in the following classes:-

Novelties made from shell cases

Novelties made from local wood

Novelties made from coconut

Metalwork

Knives, rings, pen or pencil sketch

Miscellaneous

…Prizes will be awarded in each case as follows:- 1st $5, 2nd $3, 3rd $2”

Unfortunately, however, Dad was probably unfamiliar with the contents of Routine Order No. 357 from HQ Treasury COMD quoted in the above document from Bruiser which stated under the heading “PILFERING”:

“ …it will in future be regarded as an offense for any person to be in possession of articles that have NOT been issued to him through recognised channels. Excuses that they were “given” to the possessor will NOT be accepted.

“Cases have been reported of pilfering of ammunition cases and removing hinges from ammunition boxes…parts of bombs have been removed in some cases. This is not only a foolish and dangerous practice but could lead to serious consequences for pilots. Any person caught interfering with ammunition dumps will be charged with disobedience of Island Orders which is a COURT-MARSHALL OFFENCE for which imprisonment may be ordered.”

“FRIDAY 18TH. FEBRUARY: I moved over to Battery H.Q. early this morning and now have ended my first day of “Field Punishment”. I have been working all day carrying crushed coral for the floor of the Padre’s Chapel. I was “equipped” with shovel, and a truck load of coral, two buckets and the place to put the coral. Also I have had to put in some time after each meal to help wash up the dishes and scrub tables etc! I am being completely snubbed by all the officers and feel just as a Jap prisoner must feel when he does forced labour for the Yanks.”

Presumably, the remains of the .50 calibre round was confiscated and returned to the Americans.

A footnote to this episode provides another perspective on the inappropriate use of ordinance, provided by Reginald Newell: the wife of Major General Harold Barrowclough, overall commander of the 3rd New Zealand Division in the Pacific, recorded that when he left, the Pacific the American brass (forgive the intended pun) wanted to give him a farewell gift, part of which required some sort of metal clasp. To Barrowclough’s shock, they gave orders to fire off an artillery round so that the brass casing could be cut up and used to manufacture the clasp.

He was appalled by this profligacy, as one who in his position of authority had to account for the New Zealand government for his forces’ use of war materiel. It would be fascinating to know what form this farewell gift took, and, where it is located today.