The introduction to the three diaries was written sometime after the war. In it Harry recounts his conscription and training in the New Zealand Army just before the outbreak of World War 2 in Europe. There is no handwritten copy, which suggests he wrote more or less directly using the typewriter. My feeling is that these were notes he put together within a few years of his death in 1994 in order to give a context for the day to day records of the three diaries. He typed the title “My Military Affair” on the first page, suggesting to me that he hoped that one day it might be published.

Harry was living with his parents in a cottage (Figure 1) at Hepburn Creek to the east of the small township of Warkworth, which is around 80 km. north of Auckland, when he was conscripted into the New Zealand Army, at the age of 18, initially for Territorial training, in March 1938. The cottage they lived in still stands although it has been substantially modified and extended (Figures 2 and 3).

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

The Stone family were saw-millers, offering a service milling native timber, including kauri, brought in from the surrounding area. Harry Stone senior owned the sawmill, which appears to have been moved around to several locations and employed a small number of men, including my father and his brother Bob.

The family were also involved in boating and boat building activities, often making the journey by small boat up the Hepburn Creek to the Mahurangi River and onward to the township of Warkworth. Photographs in the family album from the time show my father and mother Adele motoring around and fishing in their small boat “Kiwi” in the creek next to a bridge (Figures 4, 5 and 6) near to the house, which, like the nearby house, still exists. It must have been, in many ways, an idyllic lifestyle.

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

Dad was to be a Private in the Fifteenth North Auckland Infantry Regiment. His brother Bob drove him across country in his Model A Ford “Lizzie” (Figure 7) to the train station at Kaipara Flat, where he boarded the express train north to Whangarei and the Kensington Military Camp, a converted horse racing track. Figure 8 shows Harry presenting arms at the camp.

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

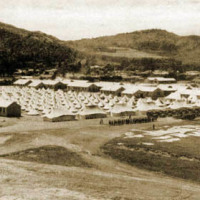

He describes his initial impressions on arrival at the camp after traveling with a trainload of other recruits from Warkworth:

“Just inside the camp gates we ‘debussed’, were assembled into three lines and marched in to an area where a large number of tents were standing ready for our occupancy. They were good tents, the oblong type, with a fly, fitted over a wooden frame, the grass was all neatly cut around them and half of them were already occupied.” (Figure 9)

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

One of the first jobs for the new recruits was to make a crude mattress, which Dad calls a “paillasse”, by stuffing a large sack with straw to be placed on a wooden slat bed in the tent. They were then given “a wide-brimmed hat, to be persuaded into the familiar kiwi soldiers’ ‘lemon squeezer'”.

The photographs in Figures 10 and 11 show Dad’s fellow inductees, complete with “lemon squeezer” hats, relaxing in the sun at the military camp. The stadium on the right in Figure 11, which Dad mentions in his Diaries, still exists, beautifully restored but moved to a different location within the park (Figure 12).

A photograph of Harry’s Company marching through the city of Whangarei records Harry, rifle over his shoulder, at the front of the middle file (Figure 14).

Upon his release from basic training, Harry worked in Charlie West’s sawmill in Helensville, 40 km north of Auckland. When war was declared against Germany in 1939, my father was called up for “permanent military service in His Majesty’s forces”. For a while, he operated a searchlight attached to the 9th. Heavy Artillery Battery at Castor Bay on Auckland’s North Shore. The Castor Bay Military Camp was situated on the cliff top with spectacular views over the Hauraki Gulf and Rangitoto Island. According to the Kennedy Park WWII Installation Preservation Trust website, http://www.kennedypark.org.nz Castor Bay was one of three gun batteries whose purpose was to defend the northern approaches to the Rangitoto Channel; the others were at Whangaparaoa and Motutapu. Harry was initially given training on the two six-inch guns facing out into the Hauraki Gulf. The guns were cunningly disguised as houses with fake roofs and facades which could be moved back to expose the guns (Figures 15, 16 and 17).

http://www.kennedypark.org.nz

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

Dad soon got bored with the relentlessly repetitive training on the big guns and requested a transfer to the two searchlight emplacements housed in concrete pill-boxes on the cliff below. He enjoyed operating the searchlights, which were similar to those in the newspaper photograph I found amongst his personal effects (Figure 18). He describes how they worked in his Introduction:

“It didn’t take me long to find out a few facts about the searchlights, 210 million candlepower, they ran on 90 volts and used 100 amps. A person could read a newspaper by the light at 25 miles and a whopping big diesel (generator) was being installed in an underground room between the houses.”

The remains of the concrete pill-boxes are still there (Figure 19), although the lights were removed soon after the war, along with the guns from the emplacements situated above. Harry describes what it was like when the guns were test-fired over his head while he was manning one of the searchlights:

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

- Figure 20

“We had one live shoot while I was at Castor Bay, it was a daylight exercise so our light wasn’t required, though we had to man it for the record. I was on the phone in the cubicle and relayed the orders to my fellow crewman. N.C.O.’s manned the gun and an oil drum was dropped by a navy boat half a mile out to sea for a target. When the order was given to fire from the Command Post, there was an almighty shock wave, followed by one hell of an explosion as the six-inch shell roared above us and out to sea. The splash wasn’t too far off the target and the shell did not explode, so I guess it was only a dummy shell, but it would have made a nasty hole in a sub or boat.”

I discovered two snapshots of the searchlight emplacements in the family photo album. They were probably taken in the late 1940s by my father. I believe the two women in the foreground of the photograph in Figure 19 to be my mother and her twin sister Beryl. The searchlights have already been dismantled in the photographs and the sites closed off to the public. The cliff face is very unstable (Figure 20). Efforts are being made by a historical preservation organisation to preserve the sites and make them accessible to the public.

On October 10 Harry married my mother at Saint Matthew-in-the-City Anglican church in central Auckland (Figure 21). He was given one week’s leave. The bridesmaid on the right is Mum’s twin sister Beryl, the one on the left her brother Ken’s wife Norma. The two men were a couple of co-opted Army mates of my father’s whom Mum had never met before.

At the end of 1942 Harry was ordered to report to the Papakura Camp in South Auckland (Figure 22) for training in preparation for being sent overseas. It was here that the 54th. Anti Tank Battery was formed:

“Gradually it came out that we were to form an Anti-Tank Battery, which threw us once more into confusion – we were obviously going to have contact with the Japs, but what would Japs be doing with tanks in the jungle?”

An insignia was drawn up, lucky number 13 chosen, and the motto Nihil Bastardis Carborundum (“Don’t let the bastards wear you down”) agreed on (Figure 23).

- Figure 21

- Figure 22

- Figure 23

Although he does not mention it in the diary introduction, this must have been when Harry met the commander of the 54th. Anti -Tank Battery, Major Robert Mason Foreman (Figure 24). Dad never used his full name in any of the diaries, referring to him by his nickname “Bruiser”.

Early in 1943 Harry’s unit was sent to Trentham Camp near Wellington (Figure 25). Adele moved to Wellington and was ordered to report to the Manpower office, who directed her to work in the Ford Motor Company at Seaview, Lower Hutt (Figure 26). The assembly plant had been converted to manufacture Bren-Gun Carriers, Jeeps, hand-grenades, and ammunition. This building, opened in 1935 to assemble Ford automobiles, still stands, and although it is no longer owned by Ford, was recently refurbished. Harry and Adele were able to see each other frequently and explore Wellington together.

- Figure 24

- Figure 25

- Figure 26

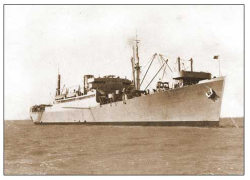

On 2 February 1943 Harry left Wellington for New Caledonia onboard the U.S.S. Fuller, (Figure 27): “an old destroyer from World War 1, now used for troop transport. I noticed she had some useful looking big guns fore and aft. With them and her good turn of speed no doubt she could look after herself quite a bit. Anti-aircraft guns were all over her, as were the inflatable life-rafts…

“…I walked up the gangway with my kitbag containing my worldly goods, my rifle and a sad heart, after a tearful farewell from my wife, to an adventure that gave no clues as to what, where or why. I was shown to my berth, damn near on the keel, and watched over the rail as our trucks were lifted like bundles of straw up off the dock, over the rail and down into the holds of the ship.”

(According to United States Navy records, the Fuller was a 8000 ton Heywood class attack transport built in 1919. She ferried U.S. Marines from Wellington to Guadalcanal in the initial assault on 7 August 1942 and continued to transport Allied troops to the Pacific theatre throughout that year and well into 1943. She was also involved in the invasions of Saipan, Tinian, Espiritu Santo, Okinawa and the Philippine Islands.)

After the war, the American Government installed a commemorative bronze plaque on the Wellington waterfront marking the location the transport ships left from for the Pacific theatre during the war (Figure 28).

- Figure 28

- Figure 29

Below the larger plaque is another expressing thanks to the people of New Zealand from the Second Marine Division Association (Figure 29). Included in the inscription are the hopeful words from a now-distant era: “If ever you need a friend, you have one.”

The two commemorative plaques overlook the waterfront location that American transport ships left from for the War in the Pacific, and from where Harry Stone’s overseas adventure most likely began. The photograph of the site in Figure 30 was taken by the author in 2016.