What is meant by image migration? The term refers to how an image created for one purpose may be re-used, re-imagined, re-formed and/or re-contextualised with or without the author’s permission. It can also relate to the way memory and meaning can be transferred across generations.

Image migration may (and frequently does) involve adapting the original image to a different medium. Image appropriation, transference and migration can have the effect of completely changing the appearance as well as the very meaning and purpose of the original. Image migration can be across physical distance and barriers as well as across new forms of technology. Images originally created for a specific audience may now be available to anybody through the medium of the internet. Image migration can involve the transference of associated cultural and historical meaning and usage. Or not.

During an age and under circumstances when issues of copyright and appropriation were deemed of minor importance, copying and adapting other people’s images by servicemen was common. This applied to official usage as well as by individuals: a single photograph or image might be used for many purposes, be it part of a propaganda message, war-related publication, conversion into a different medium, such as photograph to painting, or simply as a part of re-contextualising the image.

The use of photographs as the basis for artworks and other visual productions was common practice amongst amateur and official artists during the war years. With the likelihood of their artworks being reproduced for commercial purposes very slight, servicemen had few reservations about reusing imagery they came across in newspapers and magazines, photographs, cigarette cards and other printed sources. There appears to have been no stigma connected to copying from another source and adapting it to one’s own requirements, on an amateur or official level.

Official war artists’ drawings and paintings were frequently reproduced in war related books and pamphlets, rarely in colour, more commonly in low quality half tone. The artists’ names were usually omitted: the picture simply described as being an “artist’s impression”. A good example is Russell Clark’s “Action, Falamai Village” (Figure 2). The painting was reproduced in “Stepping Stones to the Solomons”, (one of a series of books on New Zealand’s war published by A. H. and A. W. Reed after the war) as a black and white plate (Figure 3). The reproduction is extremely contrasty and lacks the subtlety of detail and colourisation inherent in Clark’s original with its delicate washes of olive greens and tan browns.

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

The effect of the monochromatic reproduction is to almost create an abstraction of the original, with shapes and details taking on a graphic two-dimensional quality. It must have been disappointing for the artist to see his work drained of much of its sensitivity on the printed page. Perhaps he was even grateful that his name was not attached to the reproduction.

Official war artists frequently based their work on photographs taken by others. Figure 4 shows a painting of a Lockheed Ventura medium bomber by NRZAF official war artist Maurice Conly, along with the original photograph it has clearly been based on. Ventura bombers were operated by RNZAF No. 4 Squadron out of Henderson Field (Figure 5).

The painting, with no date, but likely completed after the war, is almost identical to the original photograph. Conly has changed the background, which appears to be loosely based on Honolulu, and has pointed the dorsal gun turret off to the side for compositional reasons. Not surprisingly, Conly has changed the markings of the aircraft in the photo from American to New Zealand insignia in his painting. He has slightly raised the angle of flight of the aircraft within the picture frame to subtly enhance the dramatic tension of the image. Also to add drama to the picture, he has added a second aircraft in the background and anti-aircraft flak explosions below, a complete fiction if the landscape below does represent Hawaii: Conly has taken considerable liberties with the historical truth here.

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

The original image still has currency: it was recently used in a History Channel documentary on the War in the Pacific (Figure 6).

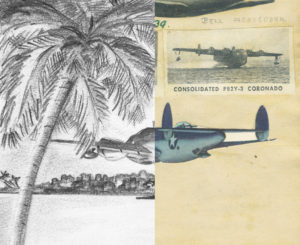

An interesting parallel example of adapting a different photograph of the same aircraft type by a regular serviceman is seen in a pencil drawing by A.O. Pollock (see separate section on Pollock in the website). Pollock produced a drawing of a RNZAF Ventura bomber apparently flying very low over a lagoon with its wheels retracted, and dangerously close to the coconut trees that frame it (Figure 7).

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

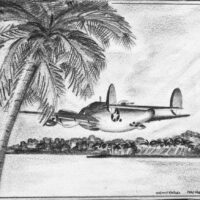

The drawing is a composite picture incorporating a photograph of the aircraft, a hand-trimmed copy of which is found amongst a collection of illustrations of aircraft carefully stuck into Harry Stone’s third diary (Figure 8), and a tropical scene recorded by Pollock on another occasion, or from his imagination.

Pollock’s rendition of the Ventura is so close to the original magazine photograph that the two can be perfectly overlaid, indicating that it was probably traced. Using a computer to adjust the relative sizes of the drawing and photograph, it is possible to line the front and back sections of each up perfectly (Figure 1). Pollock’s marriage of the image of the plane with the drawing of the lagoon has produced a strange sense of discontinuity of scale between the aircraft and its surroundings.

Obviously Pollock had seen the same reproduction as my father. Like many young New Zealand men overseas for the first time, Harry must have been excited by the advanced American aircraft he saw literally flying around him on a daily basis, and have wanted to be able to show and tell people about them when he returned home.

Many of the aircraft images in his diary appear to have been cut from magazines. Ironically for a non-smoker however, he was to discover that some of the best images of the aircraft types available at the time came in the form of small cigarette cards, which he also collected and glued into his third diary. Like young men anywhere with a passion for collecting, the troops would barter, swap and collect these cards as mementos of the aircraft types they had seen. He does not appear to have collected images of Japanese aircraft, so the possibility that the images were collected as an aid to aircraft identification, friendly or enemy, is not likely.

At the official level, a single photograph could and often was be used for a range of different purposes. Official photographs of New Zealand forces arriving near at Lunga Point to the east of present-day Honiara were printed in the Official History of New Zealand in The Second World War after the war (Figure 9). There is little evidence of this massive operation in roughly the same place today (Figure 10).

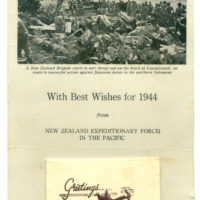

Somewhat bizarrely, one of the wartime images of the Kiwi landing was used on a 1943 Christmas calendar from the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces in the Pacific, produced by the Kiwi Printing Unit in New Caledonia (Figure 11). The calendar section itself is covered by a flap saying “Greetings…” and features an incongruous illustration of a scotch terrier dog. Why? Perhaps somebody at the printers had a fondness for scotch terriers? Perhaps the calendar itself was produced separately and added to the photograph as an afterthought? As is the case with so much of the artwork produced in the Pacific during WW2, we shall probably never know.

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

To our modern eyes, an image of invading troops landing with their supplies on a tropical beach is a strange choice for a Christmas calendar, but to the people back Home in New Zealand the image of Kiwi soldiers doing their bit to repel the threat of Japanese invasion must have been heartwarming in a way we cannot begin to comprehend. “Best Wishes for 1944” carried a very different weight of meaning for the recipient of this calendar at the end of a turbulent and uncertain 1943.

This same photograph was also used to introduce the Solomon Islands in a commemorative booklet produced by publishers Whitcombe and Tombs to mark the war history of the 36th Battalion in the Pacific (Figure 12 and 13). So too was Raymond Starr’s painting of the invasion of Mono Island (Figures 14 and 15).

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

Occasionally an artist might copy another painter’s work, especially if it held a particular resonance for the copier. An interesting example of this is the copy of Starr’s “Landing at Mono” by M. Wilson, about whom we know even less than Starr himself (Figure 16). Starr’s original version was a watercolour: Wilson appears to have used oil paint: his colours are more intense, which enhances the dramatic atmosphere of the work.

Not only is Wilson’s painting a faithfully accurate reproduction of Starr’s work, but an acknowledgement is given to the original, “From Ray Starr” being inscribed in the corner of the painting (Figure 17). It would be interesting to know what if any the connection was between these two men. Were they friends? Brothers in arms? Perhaps they had both been on Mono and this was a way of cementing their shared experience of the invasion? Was Wilson even a serviceman? Perhaps Wilson was simply taken by Starr’s painting and wanted to have it hanging on his own living room wall. Once again, as with so much of the soldier art produced in the Pacific during WW2, we shall probably never know the full provenance of this painting.

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

As we have seen, photographs were frequently used as the basis for other, “higher” art-forms. Using multiple photographs was sometimes very useful in creating an action scene from an otherwise static image. Some of Russell Clark’s most successful paintings had their origins as photographs, so many in fact that it is not easy to know which works were based on a photographic image and which were from his own observations.

One of the most intriguing examples of this is Clark’s iconic water-colour painting “Landing Ship Under Fire” (Figure 18). I first encountered this painting as a young child: I don’t remember the circumstances, but I believe I saw it framed, at an exhibition. To me it seemed a strange, mysterious image: I could not understand what was happening in the painting and had no idea at that time that my father had been indirectly involved in the events it supposedly depicts.

Clark’s painting superficially depicts the same event – the invasion of Mono Island, ironically code-named “Operation Goodtime”, under Japanese fire – as Ray Starr’s picture.

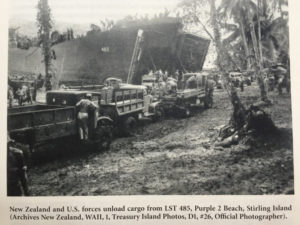

The title of the painting is non-specific with regard to the location: it is more of a generic statement about what such landings in the Pacific theatre looked like. It appears at first to show specifically LST 485 landing on Mono Island, since the historical record shows that is where the ship came under fire during the first wave of the invasion. The ship’s ID number appears on its side. However the photographs this painting was based on were actually taken on Stirling Island, where the ship encountered no such resistance. There are two photographs taken within a short time of each other, from the same viewpoint, recording the unloading of LST 485. Both images were found in my father’s collection of war memorabilia.

The first photograph, reproduced in his copy of the book “Guadalcanal to Nissan” (Figure 19), which records NZEF 3rd Division’s progress through the Solomons, has the words “MY SHIP”, written by Harry Stone below. It shows the ship pushing into the jungle with its bow doors open and supplies being offloaded (Figure 20). In the photograph, a Kiwi soldier moves into frame from the right, an American serviceman walks in from the opposite direction. Behind the American, mostly obscured, a Jeep drives off the ship. Several men stand nonchalantly next to the anti-aircraft gun high above on the bow of the ship, watching proceedings below.

This photograph clearly shows the number 85 painted on its side, number 4 being obscured by foliage. There is no indication of the scene being under attack. The New Zealand Official War History incorrectly labels this photo “A Landing Ship (Tank) Beached at Mono Island”.

The second photograph, an actual silver bromide print, which my father probably ordered from the Government Printers after the war, shows a truck now rolling steeply down the ramp from the LST (Figure 21). The American serviceman has stopped and turned to watch. Other soldiers mill about, also watching the truck descending the ramp. American soldiers mingle with New Zealanders. Again, there is no sense of urgency.

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

- Figure 20

The ship in Clark’s painting is under attack by the Japanese: a mortar bomb explodes on the ship in the background (Figure 22). Soldiers run about in the foreground, seeking cover (Figure 23), hastening to offload the ship while it is under fire. We are reminded of the figure studies Clark made of soldiers under fire for his painting “Action in Falamai” (Figure 24).

To use a modern term, Clarke has “appropriated” these photographs, combining them and adding details to create the impression LST 485 is under attack. He makes a number of changes in his painting. He faithfully inserts the entire ID number of the ship, adding the number 4, for historical accuracy in his painting. This is ironic, because while he deliberately avoids including a specific location in the title, thus making the scene a generic one, in other important respects the work is a fiction.

He eliminates the American presence. There are no American helmets here, only British issue Brodie helmets, the “battle bowlers”, sometimes called “jungle bowlers” in the Pacific, worn by Kiwi soldiers. He wants to create the impression that this is a solely New Zealand Army action, which is historically incorrect.

- Figure 22

- Figure 23

- Figure 24

While LST 485 did land on Mono Island in the first wave of the invasion, the record shows that this vessel later, after returning to collect more men and supplies from Guadalcanal, landed on Stirling Island, which accords with the fact that it is practically enclosed by the jungle. A side view of the scene (Figure 25) gives a wider context from which we see that the location is inconsistent with the layout of Falamai on Mono Island. The number 485 is now clearly visible on the side of the ship. The caption below this Archives New Zealand photograph clearly and accurately states that it was taken at Purple Beach 2 on Stirling Island, not Mono Island, where the beaches were designated Orange 1 and 2.

It is interesting to compare Clark’s painting with Ray Starr’s “Landing on Mono Island” (Figure 15). We feel more part of the action in Clark’s painting. We have a sense of being enclosed by the jungle at our backs, with little room to escape the attacking forces of the Japanese.

The LST in both paintings is clearly marked 485, but Starr’s painting is more historically accurate than Clark’s. The LST in Starr’s painting is not enclosed by jungle but is drawn up on a sweeping beach, part of the larger Operation Goodtime invasion October 27 1943. LST 485 is shown on Orange Beach 1, with the second ship and support craft in the distance at Orange 2. The landscape is geographically correct, with Falamai village hinted at in the background.

Starr shows the LST being bombed as it is being unloaded, but even here there is an artistic license at play, because the ship was hit by Japanese mortar fire from the hill behind Falamai village: it was not bombed from the air. One American serviceman was killed when the ship was hit by two Japanese mortars.

In the broader context, these discrepancies are small details that are perhaps of minor historical importance. However, by appropriating the photographic evidence and taking artistic license in his depiction of the ship under fire, Clark and Starr bend the historical record and potentially create confusion, because LST 485 did not come under fire when it landed on Stirling Island.

Historical footnote: LST 485 continued to see service in the Pacific, being involved in the invasions of Saipan and Tinian Islands, before also serving in China and Asia in 1946. She was decommissioned in July of that year and scrapped in 1948.

https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/l/lst-485.html

The landing of LST (Landing Ship Tank) and the offloading of men and supplies was a popular topic of official and unofficial artists in the Pacific. The LSTs were the workhorses of the Allied War in the Pacific. There are many drawings and paintings of LSTs thrust up upon the foreshores of idyllic tropical beaches, vehicles and goods streaming through gaping bow doors (Figures 26 – 27), bringing, in the eyes of the new invaders, civilisation and hope to the assumed oppressed and deprived island population. Occasionally, their smaller cousin, the LCT (Landing Craft, Tank) might be pictured (Figure 28).

Often the identification markings of the individual ships are omitted, probably with the objective of making a more generic statement about the roles of these ships, detached from any historical detail, but also possibly for security reasons. Where the numbers have been recorded however, the historical record is enhanced because it helps to document a particular vessel at a specific time and place.

Some artists chose to make a more factual record, others to create more of an impression of what they were experiencing.

- Figure 26

- Figure 27

- Figure 28

Implicit in these images is the impression the disgorging of seemingly limitless supplies must have made on the simple, traditionally non-materialistic lifestyle of the native inhabitants, an early example perhaps of the effects of American materialistic “shock and awe” on a seemingly primitive people. The endless stream of equipment, food and war materiel must have appeared as a magical cornucopia to these people, most of whom would have had little idea of where it had come from or how it was produced. It is perhaps no wonder that one result of this prodigious influx of goods from the sea and sky amongst the people of Melanesia, after the war and the consequent discontinuation up of the supply lines, was the rise of the so called “Cargo Cult”, where life-size replicas of ships and aircraft were made from crude materials in the expectation that goods would miraculously and interminably appear from within the replicas without any form of physical human intervention other than prayer and ritual (Figure 29).

- Figure 29

- Figure 30

- Figure 31

I became aware of the irony of participating in the modern equivalent of these delivery operations soon after we touched down in our RNZAF C130 Hercules at Honiara International Airport in September 2010. The loading ramp at the rear of the plane was lowered, and the RAMSI aid materials we had brought from New Zealand were swiftly unloaded into trucks. The main difference, from my perspective, (literally) was that in contrast to the many war-time artworks I had seen, my viewpoint was in the dark belly of the delivery vehicle, looking out (Figures 30 and 31). I was standing behind the goods and supplies rather than in front of them, watching them being unloaded, whereas the Pacific soldier-artists in every case were watching the scene unfolding from the beach and depicting the operations thus.

An intriguing aspect of these images of beached ships regurgitating their contents into a “tropical paradise” is that they can be seen as being part of a genre which has its origins in the idea of a “superior” (i.e. Western/European) culture thrusting itself upon and subsuming/colonising/subjugating a weaker and “inferior” one. The beach, the meeting point of land and sea, becomes the dividing line, but also the meeting point in this paradigm: the place where first contact is made, and where trading – of goods and culture – subsequently occurs. In the past, it was frequently a point of violent confrontation as well.

In the age of exploration, “superior” European nations competed with one another to colonise the globe: ostensibly to convert the savages they encountered to Christianity; to civilise them and “save their souls for Christ”, but in reality often to rob them of their wealth, their assets, their culture, and even of their very people.

The theme of a superior civilisation condescendingly embracing the “noble savages” on a golden foreshore in glittering sunshine and thereby welcoming them into the bosom of the omnipotent Mother or Father country (and thus assuring them of protection against the other superior cultures on the hunt for new lands to exploit) has a long history, and art has an equally long tradition of representing these encounters in a very Euro-centric way.

Take for example the painting by Emanuel Phillips Fox of Captain James Cook’s April 29 1770 landing at Botany Bay (Figure 32) to take possession of the entire continent of Australia for the British king. Cook’s team has stepped out of their longboats, British banner flying proudly in the clear, bright air, and are investigating the landscape before them. On a hill in the distance, a pair of naked Aborigines are valiantly yet impotently waving their spears at the group. Cook’s associates begin to take aim at the “savages” with their muskets, but Cook, standing heroically centre frame, reaches out benevolently to stay their hand: “Hold off your weapons: take pity on these primitive folk”, he seems to be saying, “for they pose no threat to us.”

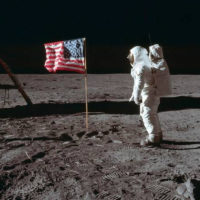

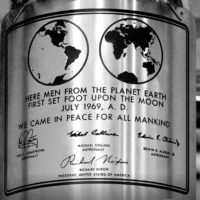

The message of the painting seems clear and has it’s parallel in the space age: “We come in peace for all mankind…” (Figures 33 and 34). While the United States declared it had no intention of turning the Moon into the 51st State when it landed its astronauts there in 1969, there is surely a cultural/historical carryover from the days when planting a flag in the ground of the latest “discovery” was all that was required under international law to “take possession” of new a territory, whether there were already people living in it or not.

- Figure 32

- Figure 33

- Figure 34

Given the subsequent humiliation, subjugation and almost genocide of the indigenous people of Australia, who had inhabited the land for the previous 40,000 years, it is little wonder that Aboriginals (and many other Australians) today refer to Cook’s arrival, and Australia Day commemorating it, as “Invasion Day” (Figure 35).

Similar scenes were enacted in New Zealand and other islands in the Pacific as the Europeans arrived to take charge. Cook’s first encounter with Maori on a beach near Gisborne in 1769 resulted in the deaths of several Maori after a series of misunderstandings.

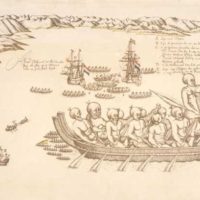

Much earlier, on December 18, 1642, the Dutch explorer Able Tasman and his crew, aboard the sailing ships Zeehan and Heemskerrck, became the very first Europeans to visit New Zealand (Figure 36). Tasman did not actually make landfall in Aotearoa. However the day after they anchored in Golden Bay, at the northern tip of the South Island, there was an altercation between local Maori and some of the crew. The sailors had been sent out in one of the ship’s longboats to negotiate with the warriors, who had paddled out to investigate the strange boat invading their home patch. This resulted in four of Tasman’s seamen being killed. Tasman promptly weighed anchor and sailed off, never to return. He named the bay “Murderers’ Bay”.

- Figure 36

- Figure 37

- Figure 38

A huge, white (the irony of its colour must be noted), featureless memorial, curiously reminiscent of the black monolith from Stanley Kubrick’s “2001 A Space Odyssey”, has been erected overlooking the bay at what is thought to be the location of the confrontation (Figure 37). (According to the New Zealand Department of Conservation, this bland structure received an enduring architecture award in 2006.)

Captain Cook was eventually killed on the foreshore of Kealakekua Bay on Hawaii’s Big Island, on his second trip to the Pacific, by the natives of Hawaii on February 14 1779. This followed a dispute about a stolen longboat, which (unknown to Cook) by the time of the altercation had already been burnt by the Hawaiians in order to harvest the nails holding it together, demonstrating that the beach could also become a place of extreme danger for the European explorers. (The native Hawaiians were fascinated with nails, and Cook’s crew removed so many of them from the Resolution’s longboats as payment to the local women for sexual services that some of them were reportedly in danger of falling apart.)

In a 1795 painting by Johann Zoffany (Figure 38), the depiction of his killing echoes the treatment given Cook in the E. Phillips Fox painting in its treatment of the event as a kind of Greek tragedy: the figures, Cook included, are shown in semi-classical, dramatic poses. The difference is that in this painting it’s the natives themselves who look like superheroes, with the English in disarray, with Cook about to be given the coup de grace on the ground. In place of the Aborigines waving spears on a hill in the background, Zoffany shows a group of English seaman being chased and overtaken by the natives.

The arrival of Cook and his crew, who brought with them European diseases including influenza, tuberculosis and syphilis, is not looked upon favourably by Hawaiians today. In fact Cook’s death is celebrated every February: according to Lilikalā K. Kameʻeleihiwa, Historian at the University of Hawaii: “We Hawaiians still celebrate every 14 February as Hauʻoli Lā Hoʻomake iā Kapena Kuke”, or “Happy Death of Captain Cook day!”

Sometimes it is possible to track the history and transformation of a specific battle location or the deterioration of a major military artefact or trophy through photographers and artists’ visual records of them over the years: images which may be used for research purposes, in books and magazines, exhibitions and websites, as well bought and sold by collectors and kept in private collections.

A good example is the fate of the Japanese transport ship the Kinugawa Maru (Refer to “The Kinugawa Maru” section of this website).

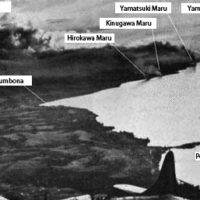

- Figure 39

- Figure 40

- Figure 41

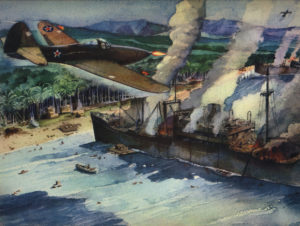

The ship and three other transports were attacked and destroyed by American war ships and planes as they attempted to land reinforcements at Tassafaronga Beach on Guadalcanal on November 15 1942. The attack was documented from American aircraft during the raid (Figures 39- 41) and the incident was later painted by American war artist Robert Laessig (Figure 42).

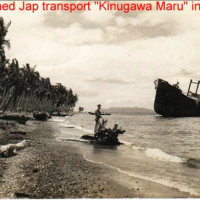

The Kinugawa Maru and the other two ships were abandoned by the Japanese, two of them slipping beneath the water, the Kinugawa Maru remaining upright, with its bow on the beach and stern under water (Figure 43 – 45).

- Figure 43

- Figure 44

- Figure 45

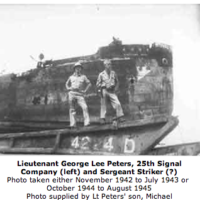

The wreck of the Kinugawa Maru became a tourist attraction even during the war, and it was common for servicemen to pose in front of it for a photograph, thus transforming its status from Japanese shipwreck into a giant American war trophy (Figures 46 -48). In his war diary, Harry Stone writes about visiting the wreck, swimming around it and climbing over it, while stationed on Guadalcanal. There is very little of the ship left above the surface today, as I found when I made my own visit in 2010 (Figure 49).

- Figure 46

- Figure 47

- Figure 48

We can track the disintegration of the Kinugawa Maru through images, from the attack in 1942 until the present day, when it has become a popular dive-site promoted on adventure holiday websites (Figure 50). The outline of the submerged wreck is also visible underwater on Google Earth (Figures 51 and 52).

- Figure 50

- Figure 51

- Figure 52

Over time such a trophy/wreck, battered by the sea and elements, will rust and disintegrate and eventually disappear from sight. Perhaps, as in the case of the Japanese transport ship, it is broken up, piece by piece, by the locals to be recycled as scrap metal (Figure 53). The trophy/wreck thus served its purpose as a tangible reminder of the war for a generation or two, then was gradually assimilated into the history books and the local economy.

In the meantime, visitors took photographs of themselves next to the trophy/wreck as it decayed their own visual memento. The material reality of the war trophy, and the visitor’s connection with it, is confirmed by the placement of the soldier/visitor in the photograph. Depending on the relationship of the visitor to the war trophy being photographed, the body language or stance of the visitors as they pose for the camera may reflect their perceived status and mental attitude as victors and conquerors. The soldiers posing in Figure 46 are a good example of this.

The photograph therefore becomes a substitute for the trophy at that particular moment in time. The trophy lives on indefinitely in the film and photographs taken home by the visitors and as images on the internet, even as it physically disintegrates over time.

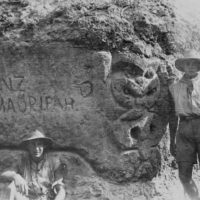

One of the most remarkable examples of image migration, this time originating from World War 1, is what was done with a photograph from Gallipoli, taken in June 1915. The photograph shows a pair of New Zealand soldiers standing in front of a trench wall that has been carved with the image of a Maori Hei Tiki and the words “Maori Pah”. The copyright for this image was, until recently (and ironically), owned by the Australian War Memorial in Canberra (Figure 54: refer also to “What is War Art” chapter of this website). The image is now in the public domain.

- Figure 54

- Figure 55

- Figure 56

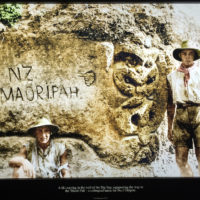

Film director Peter Jackson’s New Zealand based Weta Workshop colourised this image for the exhibition “Gallipoli – The Scale of Our War” at Te Papa Tongarewa, New Zealand’s national museum in Wellington. Using computer technology, Weta convincingly coloured in the black and white image to make it as “realistic” as possible (Figure 55). Jackson has rationalised that since the soldiers saw in colour, that was the way photographs from the war should be seen today. (Jackson later went on to colourise black and white footage from the WW1, producing the highly respected movie “They Shall Not Grow Old” in 2018: Figure 56)

The colourised version of the image raises interesting issues about “hyper-reality”, since, while the reworked image appears more “natural” and “real”, it is of course at least partly a fiction: we don’t really know what the colour of the man on the right’s neckerchief was, what colour exactly their hats were, or indeed what the colour of the rock wall was.

What makes this example of image migration especially interesting is that, not content with recreating the two dimensional photograph to make it “more real”, Weta Workshop went a step further and recreated the entire trench wall in three dimensions for the exhibition as well, as a life-size silicon model (Figures 57 and 58).

The result is the exportation of a potent image (and associated meaning) of what was originally a Maori carved art-form symbolising good luck and the ability to ward off evil spirits, from the Aotearoa/New Zealand context, “the uttermost ends of the earth”, to the Dardanelles, where it was carved into the walls of a WWI trench; transitioned from trench carving to black and white photograph; then into a digitally colourised manipulation; then back to three dimensional form as silicon model in the context of a museum exhibition.

The process of recreating the three dimensional incarnation of the image, using a process and in a material unimaginable in 1915 – using photographs, scanners and cutting edge three dimensional printers – and the creation of the subsequent Weta Workshop video documentary “The Making of Gallipoli – The Scale of Our War”, means the complete cycle of image migration is available to anyone with a computer, tablet or cellphone through the internet.

Not to mention of course any person logging on to this website from any point of the globe… including the Dardanelles.