There is little evidence available about who set up and ran the Pacific armed forces film operation, but most army camps did provide some form of cinematic recreation for their troops. Clearly the authorities, as well as supportive organisations such as the YMCA, the Returned Services Association (RSA) and the Army Education and Welfare Service (AEWS), recognised the role the movies had to play in maintaining morale amongst the men serving overseas, whether in Europe, North Africa or the Pacific.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

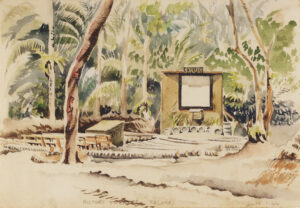

According to the Research and Archives Department at the New Zealand Army Museum, at least some of the troops in the South Pacific were shown films using a mobile cinema donated by the RSA, which toured the bases. A 35mm film projector was taken to the campsites in a truck towing a generator mounted on a trailer. The photograph in Figure 1 shows this unit; recorded somewhere in the Pacific, the exact location is not known, although it appears to be New Caledonia. The screen in this photograph is very rudimentary and appears to have been set up temporarily and for a small audience, when compared to the more permanent structures recorded in the Solomons.

Although it is not clear whether the photograph in Figure 2 was taken in the same location, or even if it was made in Europe, North Africa or the Pacific, the interior of the projector truck in Figure 1 would have looked very similar to this example. Both photographs, taken in strong sunlight, must have been set up to document how it would have operated when night fell.

Information printed in the Otaki Mail on 26 July 1943, states that the Army Education and Welfare Service organised and ran the picture programmes on behalf of the National Patriotic Fund Board, whose name appears on the side of the truck in Figure 1. In addition to providing projection equipment, this organisation facilitated regular supplies of film, including the latest American movies, through the Film Exchanges Association of NZ.

In “The Story of the 34th Battalion”, K. L. Sandford states that in his camp in New Caledonia movies were shown “at least once a week, and usually more often”. Screens were often improvised from bedsheets or similar fabric strung up between trees or iron pipes, and in one case a film was projected onto the whitewashed wall of a bakery. Seating was equally makeshift: boxes, ground sheets and blankets. Officers brought their folding stools. It seems that this distinction was maintained in Guadalcanal and Mono Island, where the best viewing spots were reserved for officers, who were provided with folding chairs, while the enlisted men had to make do with benches constructed from coconut logs, which with no back support must have been hard to sit on and very uncomfortable.

In spite of this a soldier in the Pacific is reported in the Gisborne Herald of 4 March 1944 as saying that “it is one of the great relaxations here to sit out on the hillside at night watching and listening” to the movie shows provided by the NZ mobile cinema unit (The Gisborne Herald, 4 March 1944).

In the Treasury Islands, because the New Zealand occupation was a garrison operation and therefore expected to be of a longer duration, more permanent theatre facilities were constructed, with well made timber stages that could also be used for Christmas Shows, performances by the Kiwi Concert Party, and speeches by distinguished visitors when required. As a further reminder of Home, some of the open air theatres were given the names of some of the more popular movie houses in New Zealand, especially those on Queen Street, Auckland.

Given the importance of the cinema and the theatre stage in the jungle to the troops’ morale, it is not surprising that there are so many images depicting them, by American as well as New Zealand artists.

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

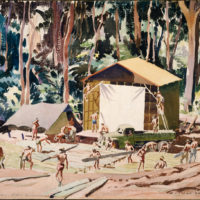

Alan Barns-Graham’s painting in Figure 3 depicts a sturdy, relatively permanent looking construction (especially compared to the later creations in the Solomons) provided for the soldiers of the 1st Battalion NZ Scottish Regiment in New Caledonia. In addition to the outdoor theatres in New Caledonia, there were New Zealand or American setups on Guadalcanal, Mono Island, Stirling Island, Nissan Island and Vella Lavella.

Two photographs from “2 NZEF IP: Pacific Pioneers: the story of the Engineers of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in the Pacific” published by Reed Publishing after the war, show the “St James” theatre at Falamai on Mono Island, built by the 29th Battalion, and the “Joroveto” theatre on Vella Lavella (Figure 4). According to author Clive B. Sage, writing in “Pacific Pioneers”, the Jorovito was built in a natural amphitheatre which could hold up to 3,000 men:

“The Joroveto amphitheater… was such a pleasant spot in consequence of our fitting it up that even on the wettest night chaps could be found waiting patiently for the stroke of 7.15 p.m…Here we listened in amazement to the Vella native Christians singing Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus unaccompanied and in excellent English. On this stage, Christmas Eve, 1943, Padre Voyce of Kahili, Bougainville, paid public tribute, on our behalf, to the loyal and enthusiastic support of the fine native people of this island. The bats wheeled overhead with short shrill shrieks; around our socks, trouser legs neatly tucked in, the mozzies whispered.”

Figure 5 shows Russell Clark’s watercolour painting of men constructing a theatre and stage at the Field Maintenance Centre on Guadalcanal.

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

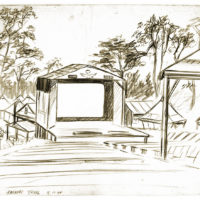

Maurice Conly’s pen drawing of the theatre at Guadalcanal (Figure 6) appears to show the facility created for the New Zealand Air Force on that island: it was close to Henderson Field. The distinctive RNZAF emblem, featuring an eagle with outstretched wings, also seen in several examples of handcrafted jewelry by air force personnel, is shown above the stage. The seating appears to be more comfortable than what the foot soldiers were accustomed to: no rough coconut logs for airforce personnel!

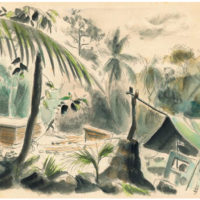

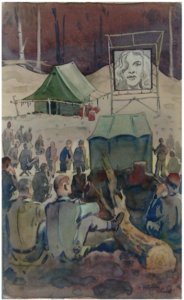

Figure 7 is a watercolour painting by Ralph Miller. It shows an outdoor theatre setup but there is no information on the painting recording where this was located. From the wooden cladding surrounding the stage area, the position of a projection box in front of the stage, and the close proximity of the coconut trees, it appears that this is the Torahatup theatre on Nissan Island (Figure 8). The canvas structure in the foreground is curious: it appears to shelter electronic equipment.

The theatre in Oscar Kendall’s watercolour (Figure 9) is easier to identify: it is the St. James at Falamai on Mono Island. Harry Stone would have been very familiar with this theatre. It is interesting to compare the painting with the photograph of the site in Figure 4, taken from a similar viewpoint. Note the coconut log seating, used in many of these facilities for the troops, compared to the relatively comfortable seats with backrests reserved for the officers next to the projection box. Note also the projection box constructed from coconut logs, similar to that in the photograph of the setup at the Torahatup theatre.

William Reed also made a painting of a theatre on Mono Island, but his style is much different than Kendall’s. In fact, while there are some similarities to the St. James, it hardly looks like, and in fact may not have been, the same location. The screen here is strung up on bamboo poles, there is a tent to one side not shown in Kendall’s version, and the jungle backdrop looks quite different. In Reed’s painting, typically, there is a slightly surrealistic tone, with artistic license being taken in the representation of the jungle and the hills the theatre is set in, which bear no relation to any of the available photographs of theatres on Mono Island.

Growing up in Henderson, West Auckland in the 1950s, the author’s family and friends didn’t go to the “movies”. We went to the “pictures”, the term derived from one of the earliest names for the medium: “moving pictures”. Or we went to see “a film”. We watched the film at a “picture theatre”.

The term “movies” was regarded as an Americanism not widely used in New Zealand in the years after the war. My father never referred to “movies” in his diaries, and in my memory never spoke the term: they were always “films”. Which is interesting in itself because so many of the movies the Kiwi servicemen were shown, whether they were Hollywood westerns or propaganda films such as “Know Your Enemy: Japan”, or instructional films about disabling bombs, were American productions.

“18th July (Sunday) 1943: Went to the pictures tonight but came back after about an hour. They showed an instructional “Bomb Disposal” film, Part I, II and III. The audience was very disappointed, and the wisecracks and exclamations of protest were worthwhile hearing. They advertised the picture as ‘Divide and Conquer’, but that was only a short one, compared to the ‘Bomb Disposal’ film. I didn’t see the latter, Jack and I had had a belly full before the first lot was over. It was interesting enough but as we were expecting something different and didn’t like ‘talking shop’ it didn’t go over too well.”

Harry Stone, Diary No. 2, New Caledonia

The “pictures” were a very popular form of entertainment and escapism for both the New Zealand and American troops. The films were mostly supplied by the Americans so naturally tended to be Hollywood productions. As can be discerned from the Diary quote above, the men wanted to be entertained and transported, not lectured to.

Note: “Divide and Conquer” was a propaganda film in a series called “Why We Fight” by Robert Capra, commissioned by the American government to explain and justify to American soldiers their country’s involvement in the war (Figure 11).

At a time when New Zealand culture was increasingly pivoting away from the influence of the British “Mother Country” and toward the emerging lingua franca of American popular culture, Harry was conscious of the differences between his own New Zealand experiences and the American culture he was surrounded by. Like many of his fellow soldiers, he appears to have been at once fascinated and repulsed by his experiences of Americans.

“Wednesday 24 March 1944: “By God I’m getting fed up with this (NZ) army. I told the boys last night I’d rather be in the American army any day than this outfit and by cripes I meant it!”

My father told several anecdotes about the different attitudes and speech used by the American soldiers he came in contact with. He told me that a G.I. had explained to him that the American pronunciation of the word “vase” rhymed with “Mars” if it cost more than a dollar, but with “maze” if it cost less.

In Diary No. 1 on May 23, 1943, he recorded an incident at a joint New Zealand/American picture session at one of the aerodromes, probably the Plaine des Gaïacs facility at Pouembout in the north of new Caledonia:

“I have found out why the N.Z. boys were stopped from going to the pictures for about a fortnight a while back. The N.Z. piquet, (Infantry), were on duty at the aerodrome where the pictures were held, when some Yanks started talking to the guard at the gates. They declared N.Z. was a “brothel” of a country, so one guard lay down his rifle and bayonet and started on one Yank. Then more Yanks came and more infantry, until it developed into a grand brawl. The American nurses, (from the Hospital), when wishing to go to the pictures, have to go with an armed guard, because of the way the Yank troops behave. The nurses usually keep out of sight in the projector box shed. When they arrive and leave is when the trouble starts, the kindest thing I have heard them say is, “Chuck your tits out, sister”.

Nevertheless, Harry had a favourable regard for many things American: not only for American movies, but American technology as a whole, and in the years after the war, for President Kennedy. After Dad died in 1994, I found a head and shoulders newspaper photograph of the murdered President in the drawer of his writing desk. Kennedy’s motor-torpedo boat, the PT 109, had been famously rammed and sunk by a Japanese destroyer only 150 km south-west of the Treasury Islands on August 2, 1943, a few months before my father landed on Mono Island.

The movies clearly provided respite and escapism for the American servicemen as much as for their Kiwi brothers in arms. In his notes on the open-air theatres on Guadalcanal in the book “From Fiji Through The Philippines With The Thirteenth Air Force”, the American war artist Robert Laesseg writes:

“Tonight and every night was theatre time in the Thirteenth. If your own organization showed movies only three times a week, there was always one showing not far down the road at a neighbouring camp. Around seven o’clock in the evening, dusk faded into darkness, and men began to wander to the movie area to find a seat for the show, relax and to escape into another world, where the tropics could be completely forgotten.”

“Along with food and mail, the movie was an indispensable aid to morale. For men who had been out of touch with civilisation for months and even years, movies formed a link with the past, and helped them to return to the world from which they had been separated.”

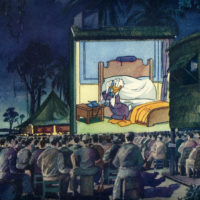

It is interesting to compare Laessig’s painting of a screening on Guadalcanal (Figure 12) with Russell Clark’s painting on the same theme at Malsi on the east coast of Mono Island (Figure 13). The main difference is in the circumstances of the men watching the film: the American audience sits in relative comfort under a starry sky watching Donald Duck, while the Kiwis stand in torrential rain ogling a Hollywood starlet. The context of Laessig’s depiction is therefore very different from Clark’s: the American soldiers have the security of being surrounded by many thousands of their comrades in a relatively stabilised location on Guadalcanal, while the New Zealand soldiers position in far-flung Mono Island is far more tenuous, and closer to the front line, or what passed for one in the Pacific at that time.

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

Both images in their own way comment on the banality of men at war craving this evanescent form of escapism to take their minds off their present circumstances. Both express the common wish of the soldier to be elsewhere, and of the cinema’s powerful ability to psychologically transport the audience to another world, or at least another part of this one.

Laessig’s painting contrasts the soldiers’ potentially life-threatening experience of being at war that exists in their world, with the escapist, fantastical world of an animated Walt Disney film.

However Clark’s painting arguably makes a more poignant comment, as it also addresses the sexual frustration and pining for wife and family, that must have been a constant factor in many of the men’s daily lives, as they stand in a tropical downpour at night, taking in the flickering image of a Hollywood starlet projected above them on the rain-drenched screen.

“Save for the pictures, and one or two USO shows at nearby camps, there was no entertainment on Guadalcanal. We built a theatre in our own area, to which visitors from other camps would come, New Zealand and American, just as, when we were not showing pictures, we would walk or ride to their camps to see what was on there.

“It was singular that in the Treasury Islands, far-flung little British outpost near the equator, we enjoyed more entertainment than at any previous time in our history. This was partly due to the vital necessity of combating the hardships of climate and environment, and the knowledge that we must go to more than usual lengths to amuse ourselves. Once again the staple form of entertainment was the film. At Malsi we carved out a theatre, with seating accommodation for upwards of 600, and with a stage large enough for visiting concert parties. Soanotalu and Luana did likewise, though on a smaller scale. Films were regularly shown at all places, at least once a week, and usually more often. There were two visits from the Kiwi Concert Party, that admirable combination of artists, and one show from the 8th Brigade party. Several American USO shows were also presented. For the delight of the swing fan, an American regimental band gave a few programmes, playing in the heat of the mid-day sun on the beach at Malsi. Somewhat in the same style was the unusual concert by American coloured troops who arrived to relieve us in the Treasuries, and gave us this entertainment as a farewell gesture.”

K L Sandford: “The Story of the 34th”: Entertainment” (Reed Publishing)

(The New Zealand Electronic Text Collection)

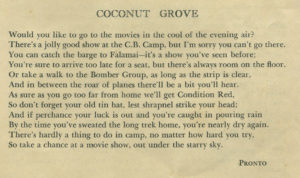

The short poem reproduced below (Figure 14), titled “Coconut Grove” and written by somebody only identified as “Pronto” in the book “History of the 36th Battalion in the Pacific”, could just as easily have been written by my father. Clearly it was written on Stirling Island where Harry Stone was stationed: “There’s a jolly good show at the CB Camp (American SeaBees construction camp – this was on Stirling Island) but you can’t go there (out of bounds to New Zealand personnel), you can catch the barge to Falamai (on Mono Island)…” (and watch a picture at the St. James instead).