The information in this section is of necessity a synopsis of the events. For a more thorough account of the history of the Third Division I recommend reading Reginald Newell’s doctoral thesis “New Zealand’s Forgotten Warriors: 3NZ Division in the South Pacific in World War II”, which is accessible on-line at:

https://mro.massey.ac.nz/handle/10179/753

The formation of the New Zealand 3rd Division and its deployment in the Pacific is a complex and interesting story. In many ways this period in New Zealand’s history marks the beginning of a cultural shift away from the country’s attachment to Britain, the “Mother Country”, to a closer identification with America.

The 2nd Division fighting in North Africa and Greece was part of the Second Expeditionary Force (the First had been sent to Europe in WW 1). The 3rd Division was the main Army unit of the Second Expeditionary Force in the Pacific. Originally made up of three brigades, the 15th was disbanded in 1943 due to shortages of manpower leaving just two brigades: the 8th and the 14th. The 54th Anti-Tank Battery was attached to the 8th Brigade, which was charged with taking the Treasury Islands. The 14th Brigade invaded Vella Lavella and the Green Islands.

The abbreviated name for the Pacific Division was 2NZEF-IP. Harry Stone’s official Army service record contains no reference to the specific locations he served after he was shipped overseas: these are described simply as IP: “In the Pacific”.

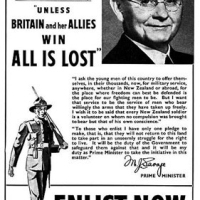

When the War in the Pacific erupted with the Japanese surprise bombing of Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941, New Zealand was put in a difficult position. The policy of the Labour government under Michael Savage (Figure 1) and subsequently Peter Fraser (Figure 2) was to support Britain directly by sending troops to the European theatre. This reflected public opinion at the time and the tradition of allegiance to the “Mother Country”. Savage, who was Prime Minister when New Zealand declared war on Germany (just hours after the British) and who died of cancer in 1940, declared from his hospital bed:

“With gratitude for the past and confidence in the future we range ourselves without fear beside Britain. Where she goes, we go; where she stands, we stand. We are only a small and young nation, but we march with a union of hearts and souls to a common destiny.”

The policy was that Britain had to be saved at all costs: the war against Germany and Italy had to take precedence over all other considerations, and accordingly the bulk of New Zealand’s forces, the 2nd. Division, comprising around 2,000 soldiers, were shipped to North Africa to confront Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Africa Korps.

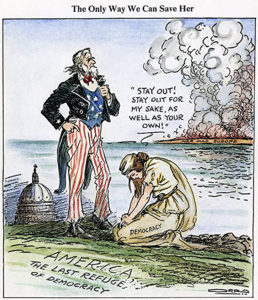

The situation for Britain in 1939 and 1940 was bleak and getting bleaker. Prime Minister Winston Churchill had pleaded and cajoled America to come to Britain’s aid, but while President Franklin Delano Roosevelt realised that Hitler had to be stopped and wanted to support the British, he had been elected (for the third time) in 1940 partly on his promise to keep America out of the war.

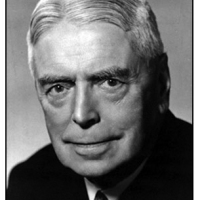

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

He had bowed to public pressure in his second term in 1935 when he signed the Neutrality Act into law, banning any shipment of arms to any combatant nation (Figure 4). While he continued to promise the United States public that the sons of Americans would not be sent to die in any foreign war while he was president, thus appeasing the isolationists who did not want to join the war in Europe under any circumstances, FDR surreptitiously supplied all the assistance he could short of actual military equipment.

When Churchill heard of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, and America’s immediate declaration of war on Japan and Germany, he exclaimed: “So we have won the war at last!”

When Japan entered the war, Fraser had to decide whether to bring New Zealand troops back to defend New Zealand from the Japanese threat, or keep them in the Middle East. Many in New Zealand felt that the country should withdraw its forces from Europe to protect its own back yard in the Pacific, which is exactly what Australia did following the Japanese bombing of the northern city of Darwin and the invasion of New Guinea. Churchill, pressuring the New Zealand government to keep its 2nd. Division in Africa, told Fraser “not to worry about the Japanese”. Fraser decided to leave the New Zealand troops in the European Theatre.

Ironically, the fear of a Japanese invasion of New Zealand felt by the New Zealand public, while understandable, was probably exaggerated. The Japanese had no official intention of invading Australia or New Zealand in spite of arguments put forward by elements within the military. Their emphasis was in creating the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” in Asia and Oceania (Figure 4), citing “Asia for Asians” as their goal.

Their objective was to isolate Australia and New Zealand, which would then be used as “bargaining chips” in a peace agreement with the United States. For this reason, control of Guadalcanal was essential for the Japanese, to provide a base and airfield for attacking American supply lines across the Pacific to Australia. And that is why it was crucial for the Americans to capture it. The fight for Guadalcanal marked a turning point in the War in the Pacific: a battle the Americans simply could not lose.

Of course, we don’t have a crystal ball, and more to the point, neither did the populations of Australia and New Zealand at the time. There were certainly elements within the Japanese military and government who were in favour of eventually invading both countries, and who knows what might have transpired after a “peace agreement” had been negotiated with the American government?

With the British fighting for their survival in Europe, the war in the Pacific was effectively left to the United States to conduct, and there is no question that the America bore the brunt of the war to contain and defeat Japan’s ambitions. But New Zealand wanted to be part of the action also, partly because it wanted to participate in the post-war negotiations to decide the political future of the Pacific area. New Zealand wished to be regarded as a relevant player in the region, and ultimately was to be rewarded with a symbolic presence in the person of Air Vice Marshall Sir Leonard Isitt at the signing of the Japanese surrender on board the USS Missouri in Tokyo Harbour on September 2, 1945 (Figure 6).

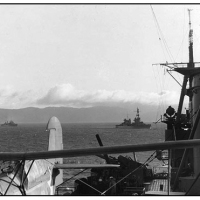

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

As Britain prepared to fight the war in Europe in 1939 and 1940, it became New Zealand’s responsibility to defend Fiji and Tonga. This had been suggested by the British as early as 1936. In discussions with Britain and America, and with its 2nd Division committed in Africa, New Zealand offered to create another full division which could be used to relieve an American division. But in reality the country did not possess the resources in men or materiel to create another full division as well as keep the economy operating at home. Shortages of manpower were already becoming a problem.

In October 1940 New Zealand began to send groups of soldiers and specialists to Fiji, which were designated “B Force”. Initially there were 3,050 men and this was increased to 6,050 on December 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbour. In January of 1942 B Force assumed the status of a two brigade division (the 8th and 14th Brigades), and became informally known as the 3rd Division. On May 12, 1942, B Force was officially renamed the 3rd New Zealand Division.

After the Battle of the Coral Sea north east of Australia on 7 – 8 May 1942, Vice Admiral Robert Lee Ghormley (Figure 7), the newly appointed American commander of the South Pacific, informed New Zealand that the United States wished to take responsibility for the defense of Fiji and Tonga and insisted that the New Zealand forces be returned home. The New Zealand government suggested that some of its troops be kept in Fiji but this was rejected by the Americans, who wished to maintain unity of command and equipment within their own forces. Walter Nash (Figure 8), New Zealand’s Minister to Washington, was given the clear impression that America saw no combat role for New Zealand troops but that they could be useful for garrison duty: that is, acting in a defensive capacity.

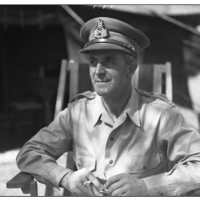

- Figure 9

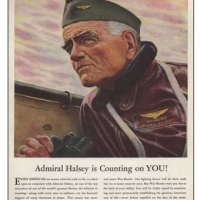

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

The Americans suggested that the New Zealand troops should be trained at home in amphibious warfare for later American operations in the north-west Pacific. By July 1944 the two brigades of the 3rd Division had been returned to New Zealand.

The commander of the 3rd. Division, Major-General Harold Barrowclough (Figure 9), was determined to get his forces into front-line action. Following lengthy negotiations with Ghormley, who was reluctant to use New Zealand forces, it was agreed that the 3rd Division would be sent to garrison New Caledonia, with a possible invasion role later on. In October of 1942 an advance party of the 3rd. Division was sent to New Caledonia to relieve an American division who would be sent to Guadalcanal (Figure 10). Toward the end of 1943 there would be 13,000 New Zealand soldiers in New Caledonia as a garrison army, training for eventual action against the Japanese further north. One of the soldiers was Gunner Harry Stone.

Barrowclough had continued to insist that there be a combat role for his New Zealand forces. Ghormley continued to express doubts about the training and determination of the Kiwi troops and remained reluctant to use them on the front line. Admiral Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the American Pacific Fleet, disagreed strongly with Ghormley’s attitude, declaring “If we can’t find a formula for using them, it’s Japan’s gain…if we can’t use our Allies we are damned fools.” Ghormley’s continuing negative attitude to the running of the war in the Pacific generally was seen as defeatist and lacking in aggression by Nimitz and he was replaced by Admiral William “Bull” Halsey (Figure 11) in October 1942.

Halsey was a colourful, charismatic and far more aggressive leader than Ghormley, who established a much better working relationship with Barrowclough and the New Zealand Government. Following discussions on the situation in the Solomon Islands, Halsey asked Barrowclough to present a request to the New Zealand War Cabinet for the 3rd Division to be sent to Guadalcanal by the end of 1943 “preparatory to active combat employment”. The move to from New Caledonia to Guadalcanal took place in three groups on 27 August, 3 September and 14 September 1943. The photograph below (Figure 12) is a scan of a newspaper photograph found amongst my father’s collection of personal effects, showing New Zealand forces preparing to leave New Caledonia for Guadalcanal.