What were the events that lead up to the War in the Pacific and how did New Zealand get caught up in it? While the political events that lead up to the War in the Pacific are complex and far-reaching, a basic knowledge of the historic events that preceded the war with Japan is important to understanding why the war took place.In the 1930s, Japan was seeking to extend her empire and influence and become the dominant power in the Pacific under the guise of creating a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” (Figure 1).

Japan’s rulers had decided that the traditional home islands were no longer enough to cater for the country’s expanding population and ambitions. They looked covetously to the vast spaces of China and Manchuria and the breadbaskets, oilfields and rubber plantations of Java, Sumatra and Malaysia to the south, countries which they believed represented “choice territory that heaven had placed temporarily in the custody of other countries”. The Japanese began referring to these countries as “The Southern Resource Area” and had visions of unifying them under Japanese rule. In anticipation of this new Japanese empire, new banknotes were designed and printed (Figure 2).

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

The war being waged against Germany in Europe provided an opportunity for Japan to challenge the British and Dutch presence in the South East Asia. In 1931 Japan had taken control of Manchuria in North Eastern China. A pretext for the attack had been created by Japanese militarists dynamiting a section of railway line owned by the Japanese controlled “South Manchuria Railway” (Figure 3). This attack, which only damaged 1.5 meters of one side of the track, (the line was reopened within a couple of hours) resulted in the Japanese Imperial Army in China, the Kwantung Army, launching a campaign to take over Manchuria. Technically, this was an act of insubordination by the Kwantung Army commander, since the action had not been authorised by the Japanese government, but, powerless to oppose the Army, the civilian government decided to consolidate the territorial gains made by quickly sending three more infantry divisions to Manchuria.

As the situation worsened, the Chinese government protested to the Japanese government and on September 19, 1931 sought help from the League of Nations. On October 24 the League of Nations passed a resolution calling for the withdrawal of all Japanese forces from China, which was ignored. On January 7, 1932 the American Secretary of State, Henry Stimson, declared that it was United States policy not to recognise any government established by the Japanese in Manchuria.

In March 1932, Manchuria was recreated as the puppet state of Manchukuo by the Japanese (Figure 5), who installed the last Chinese emperor, Puyi, as its head of state. In March 1933 the League of Nations refused to acknowledge Manchukuo as an independent nation, resulting in Japan walking out of and resigning from the League.

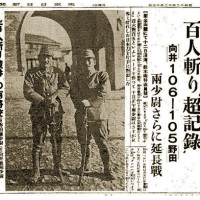

In July 1937, after a series of “incidents” between Chinese and Japanese forces, all-out war broke out on the mainland. The Japanese adopted the “Three Alls” policy: “Burn all, Seize all, Kill all”. For the first time, the world became aware of the merciless lengths that Japanese troops would go to in order to subdue their opponents. Trained in bushido, the code of the samurai, to observe complete obedience to the Shogun/Emperor and the principle of total and pitiless annihilation of the opposition by any means, the Japanese forces attacked Shanghai and Nanking, then the capital of China, slaughtering hundreds of thousands of Chinese soldiers and civilians (Figure 5). In these two cities, the undisciplined Japanese Army, “like an untamed horse left to run wild”, went on an orgy of rape, murder and pillage. Civilians were used for bayonet practice (Figure 6), and a gruesome competition between two Japanese soldiers to be the first to decapitate100 Chinese using a samurai sword was reported in Japanese newspapers (Figure 7). The behaviour of the Japanese soldiers, while not officially condoned, was given tacit approval by the officers in charge.

The overall commander of the attack on Nanking, General Matsui Iwane (Figure 8), was tried as a war criminal at the end of World War 2 and executed by hanging .

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

In the late 1930s, as war in Europe loomed, United States President Franklin Roosevelt publicly vowed to the American public that he would not involve their country in the fighting. At the same time, he was aware that if the war spread it would become inevitable that America would become involved, and he did what he could within the bounds of public opinion to support England in its struggle against Germany. “There is a vast difference”, he said, “between keeping out of war and pretending it is none of our business.”

In the early 1930s the Congress had passed the Neutrality Acts, which expressly forbade the American government from taking sides in the growing turmoil in Europe. Roosevelt couldn’t openly declare war unless or until provoked to do so by a serious enough attack on American interests. This was controversial legislation because it ignored the dangers to world peace as a result of the rise of fascism in Europe and growing militancy in Japan in favour of a policy of Isolationism. President Roosevelt used loopholes in the Neutrality Acts to enable Britain and its Allies to purchase American arms and supplies by paying cash for them and transporting them in their own ships (Figure 9).

In September 1940, Japan, conscious of the need for allies, signed the Tripartite Treaty with Germany and Italy. This meant that if any one of the three countries was attacked by the Western Allies, the other two would declare war in support. If Japan attacked America and Washington declared war on Japan as a result, America would effectively be declaring war on Germany and Italy as well. An incident involving an attack on American forces or interests by either Japan or Germany would therefore provide the excuse Roosevelt needed to enter the war against Germany.

Early in 1941, Washington insisted that Japan withdraw from China. Japan, which had lost some 300,000 soldiers in China, refused to do so. Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo wrote after the war: “Japan was now asked not only to abandon all the gains of her years of sacrifice but to surrender her international position as a power in the Far East. That surrender…would have amounted to national suicide. The only way to face this challenge and defend ourselves was war.” From this period, Japan began planning for war with America.

In July 1941 Japan took advantage of Germany’s defeat of France to over-run French Indo-China (present-day Vietnam and Laos). The United States, together with Australia, Britain and the Dutch government in exile, which controlled the oil-rich Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) stopped selling oil, iron ore and steel to Japan, thus greatly inhibiting its activities in China. The Japanese regarded these embargoes as acts of aggression. The Japanese media began referring to the embargoes as the ABCD (American, British, Chinese and Dutch) Encirclement.

Japan was now forced to look for alternative sources for the materials it required to pursue its goals in China. Its attentions turned to the countries to its south. In the longer term, in addition to seizing control of the countries of the “Southern Resource Area”, the war-plan was to isolate, but not necessarily invade Australia and New Zealand, by severing the sea links between those countries and North America. Australia and New Zealand would then be used as “bargaining chips” in negotiations after a stalemate had been entered into. Taking over Guadalcanal and constructing an airfield there was a key component of this strategy because it would enable Japanese aircraft to attack shipping en route to the two countries, as well as create a staging area for future attacks on New Caledonia, Fiji and Samoa.

Before it could launch its campaigns to take the countries of South East Asia, the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbour in Hawaii had to be neutralized. Fleet Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto (Figure 10) was charged with planning the attack. He did so reluctantly. Having been educated in America at Harvard University from 1919 to 1921 he had seen for himself the might of the American industrial machine that could so quickly be converted to war production. He told the Prime Minister at the time, Prince Fumimaro Konoe (Figure 11), who resigned his office several weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbour: “In the first few months of a war with Britain and the United States I will run wild and win victory after victory. But then, if the war continues two or three year after that, I have no confidence in our ultimate victory.” In other words, a first strike had to be effective in destroying not only the American’s ability but also its will to retaliate, and give the Japanese the time they needed to capture the “Southern Resources Area” and consolidate their empire.

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

Yamamoto was very astute in his appraisal of America’s war production capabilities. Records show that even in 1941, the year of Pearl Harbour, Japan produced 5,088 war-planes to the United States 19,433. From 1941 to 1944 Japan made 58,822 planes, the United States a staggering 261,826.

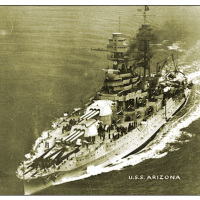

The attack on Pearl Harbour took place on December 7, 1941 (Figure 12). In spite of American fore-knowledge of the attack as a result of decoding the Japanese “Purple/Magic” code, and having recently invented radar systems in place, the Americans were taken completely by surprise. Four United States battleships were sunk, and the four others present were damaged.

The USS Arizona (Figure 12) sank at her mooring with the loss of 1,177 officers and crewmen, whose remains are entombed in the ship. In 1962 a memorial over the ship was constructed over the wreck (Figure 13). Oil from the wreck continues to leak from her bunkers to this day (Figure 14).

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

Also sunk in the attack were three cruisers, three destroyers, an anti-aircraft training ship and a minelayer. 188 aircraft were destroyed, 2,402 men were killed and 1,282 wounded. Importantly, three aircraft carriers were at sea and were not attacked, nor were the oil storage facilities, which at the time held more fuel than the whole of Japan.

The attack, designated by Roosevelt as “a date which will live in infamy” (Figure 15), instantly produced feelings of hatred and lust for revenge toward the Japanese, and any thought of remaining neutral in the conflict raging around the world was cast aside. America immediately declared war on Japan as well its Axis allies Germany and Italy.

The attack on Pearl Harbour was a brilliant strategic success by the Japanese, although two of the battleships sunk that day were salvaged and repaired and saw service later in the war, but it was a political disaster. To take advantage of the situation they had created, Japan would have to now move very quickly to achieve its goals before America rebounded.