Originally built by the Mitsubishi Shipbuilding and Engineering Company in Nagasaki, the Kinugawa Maru was used for general cargo trade around the Pacific in the period before the Pacific War.

The ship displaced 6300 tonnes and was 133 meters long by 18 meters wide. When Japan went to war, the Kinugawa Maru was taken over by the armed forces and used in the Guadalcanal theatre to deliver troops and supplies. She arrived at Guadalcanal for the first time on 25 September 1942.

In November 1942, the Kinugawa Maru was part of a supply run down “The Slot” (the area of open ocean between the two Solomon Island chains) to land reinforcements and supplies at Bonegi Beach, 13 km west of present day Honiara, where the Americans had become entrenched surrounding Henderson Field. American forces had captured the Japanese built airfield in early August, and the Japanese were determined to get it back. Eleven transports, including the Kinugawa Maru, had left the Japanese base at Rabaul, on the island of New Britain near New Guinea. The ships carried 7,000 troops and much needed supplies of ammunition, food and heavy equipment. They were escorted by twelve destroyers.

As the convoy headed south toward Guadalcanal, they were spotted by a patrol plane from the American aircraft carrier USS Enterprise at 0830 hrs on 14 November. The patrol plane immediately radioed the convoy’s position and attack aircraft were sent from the Enterprise and Henderson Field to intercept the convoy soon after midday. Seven transports were sunk, the survivors being picked up by the escort ships and taken back to Rabaul. The four remaining ships, including the Kinugawa Maru, continued steaming toward Guadalcanal.

At dawn the following day, the four ships were found just offshore near the beach at Bonegi. At 0500 hrs, American field guns 20 km away to the west of Lunga Point, near Henderson Field, opened up and hit one ship, setting it on fire. The Destroyer USS Meade, on patrol at the time, raked the Japanese ships with 5-inch shellfire. Planes from the Enterprise and Henderson Field were also mobilised to attack the four transports (Figure 2). The captain of the Kinugawa Maru, realising his ship was lost, drove it hard upon the beach before floodwaters reached the engine room so that the supplies could be unloaded. By noon, all four transports were ablaze and sinking (Figure 3). The soldiers of the Kinugawa Maru abandoned ship as it slowly settled by the stern.

Finally, after much punishment, an American fighter from Guadalcanal put a bomb into her stern cargo hold on the evening of 15 November, and the Kinugawa Maru finally sank shortly thereafter, leaving her bow and midship area high and dry above the waterline.

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

Hundreds of Japanese servicemen were killed in the attack, many going down with the ship. Of the 10,000 troops that set out for Guadalcanal, only around eventually 2,000 survived. Some were taken off by Japanese ships and taken to the Japanese base on Shortland Island. In January 1943, roughly 75 crew members from the Kinugawa Maru were discovered in a field hospital by the U.S. Army 147th Infantry Regiment. All of the patients, including these crew members, were killed.

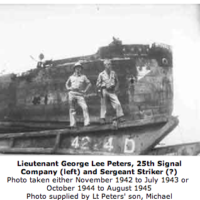

In the period immediately after the Japanese were driven out of Guadalcanal, and as Allied forces continued to consolidate their hold on the Solomons, the wreck of the Kinugawa Maru became a strong tourist attraction for soldiers and soldier-artists. In their leisure time, servicemen would drive up the coast to have their photo taken next to the ship, climb over, swim around and dive off it (Figures 5 to 7. Refer also to section on Image Migration).

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

Harry Stone visited the wreck on Monday 27 September 1943:

“I was lucky enough to be able to go on a ‘touring party’ today, we went about 15 miles up the coast and saw some interesting things, including three Jap transports lying on the beach. One was on its side, bombed to beggary, the other two were upright, but down at the stern and the bow high up out of the water. We swam out to one of them, the ‘Kinugawa Maru’, and climbed up a rickety gangway to the deck. She had been treated pretty rough while getting ashore, shells that had gone in one side and out the other, leaving gaping holes.”

Taken soon after the sinking of the ships, the photographs in Figures 8 to 10 show the Kinugawa Maru as it would have appeared to Harry Stone when he visited it ten months later.

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

At a time when the threat of the Japanese retaking the island faded, as the front line moved further and further northwards toward the home islands of Japan, life on Guadalcanal became, if not more comfortable, then at least more secure. Troops must have found they had more leisure time to explore their surroundings and come to terms with the events leading up to the defeat of the Japanese. For many, the rusting hulk of the Kinugawa Maru rearing up out of its idyllic surroundings must have symbolised the superiority of Allied equipment and fighting abilities over those of the Japanese, and their inevitable surrender. Swimming around and clambering over the wreck must have given the men a huge boost to their morale. The beached ship had become a massive, permanent war trophy, a confidence-building reminder of the progress being made in the war against the Japanese empire. Not surprisingly, the wreck soon became the subject of hundreds of photographs featuring heroic poses of servicemen gazing at or standing in front of the wreck (Figure 11).

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

Coloured photographs (Figure 12) and hand coloured black and white images (Figure 13) taken by professional and official press photographers were sometimes used as post cards. Colour film was not as popular with photographers in the heat and humidity of the Pacific, because the chemistry was not as stable as black and white film and the heat would soon turn the film stock bad. Hand colouring was therefore a popular alternative, especially when images were to be used for commercial purposes. In the case of Figure 13, the colourising lends the image a nostalgic, slightly surrealistic flavour to a modern viewer. The original monochromatic image is shown in Figure 14.

Not surprisingly, it wasn’t long before the wreck of the Kinugawa Maru also became a popular subject for official and amateur New Zealand war artists on Guadalcanal. Official New Zealand artist Russell Clark made a painting of the Kinugawa Maru and one of the other beached transports (Figure 15).

Unofficial artist Raymond Starr, who made a painting of the invasion of Mono Island (refer to the section on Starr on this website), also visited the wreck. The lashed together oil drums in the foreground in Starr’s painting (Figure 16) are particularly interesting: before sending their transports to Guadalcanal, the Japanese had attempted to float food and supplies to the desperate troops still on the island by sealing material inside the drums and setting them adrift offshore, hoping that the currents would push them toward the beach.

Dennis L. Chambers included a wash painting of the shipwreck in the small booklet “Glimpses of the South Pacific: A collection of Sketches by two New Zealand Soldiers serving in the South Pacific” which he published with fellow amateur artist Howard M. Purser in 1944 (Figure 17).

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

We have no way of knowing if these paintings were completed in the field, or even while the artists were on Guadalcanal (we do know that Clark completed many of his paintings after returning to New Zealand). They may well have been based on photographs. However, the fact that the paintings were made in watercolour and wash suggests that they could well have been made in situ. Watercolor painting, using paint tablets set out in trays, was a more popular medium than oil paint, because the tubes of oil paint would burst and leak in the tropical heat.

In the decades since she was sunk, the wreck of the Kinugawa Maru has undergone many changes. Much of the superstructure and hull above the water was cut up for scrap. The propellor was also removed for recycling. A storm twisted the ship to lay at an angle to the beach and she slipped into deeper water. Very little remains above water today, although plenty remains submerged (Figure 18 – 20). The wreck has become a very popular dive spot for visitors to Guadalcanal.

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

- Figure 20