New Zealand forces In the Pacific (NZIP) had three official artists in the Pacific in World War 2. They were Russell Clark and Alan Barns-Graham, who were both in the New Zealand Army, and Maurice Conly, who was the official artist for the Royal New Zealand Air Force. The Navy did not have an official war artist.

Official war art refers to artwork (predominantly painting) created by commissioned war artists, usually recruited from the armed forces themselves, who produce a visual record of significant battles and events, places of importance, and the daily lives of the officers and servicemen of the armed forces. The official war artist may also be called upon to paint official portraits of officers, war heroes and other important people. Official war art aspires to be ‘serious’ or ‘fine’ art, depicting major war episodes, making portraits of notable personnel, or recording the daily activities of servicemen.

Generally, the task of the official war artist is to depict the military organisation which commissions him in a positive light: engaged in battles in which the organisation is demonstrably winning or has been victorious. Official artists are not often required to depict military defeats. The wounded, when depicted, are not shown severely mutilated, in great pain or bleeding, but appear heroic in their bearing, or enduring their trials with stoicism and dignity.

Because the official war artist is appointed to his position and receives a commission, he enjoys special privileges including time off normal duties to produce his artworks. In other respects however he is still a soldier. Fighting the enemy always takes precedence over making paintings. When the enemy attacks, he must lay down his brush and pick up his rifle. For this reason, few paintings, or drawings for that matter, are made during the thick of the fighting. A photographer or cinematographer is more likely to be charged with recording a fire-fight because a camera can be quickly set aside when the rifle or machinegun are needed. For these reasons many official war artists base their ‘action’ paintings on a photographic record.

In considering the role of the official war artist, we might well ask therefore, what a painter brings to an image that the photographer does not or can not?

Firstly, there is a strong feeling, particularly amongst military bureaucracy, that the painter, through his use of composition, expressive colour and brushwork, is better able to create an impression of the actuality of battle than the coldly dispassionate camera is capable of (and that this was even more so in the era of black and white photography).

Secondly, it is felt that a painter can incorporate more of the detail of an action within a single image, thus creating a ‘truer’ representation than a camera, which (in pre-digital times at least) was limited to a single viewpoint and capturing a single instant in a multitude of associated events. Thus, a painted representation can produce a form of ‘hyper-reality’ that surpasses the documentary ability of the camera lens, no matter how good the photographer, by conjoining related episodes into one depiction.

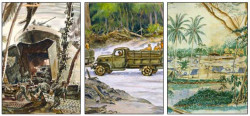

Russell Clark’s “Landing Ship Under Fire” (Figure 1) is a good example of this. The painting, made after the war, depicts events that occurred on 27 October 1943, but is based on two official photographs of LST 485 landing at Stirling Island, which were probably taken a few days after hostilities ceased. In the photographs, American and New Zealand servicemen can be seen milling about, unloading equipment from the ship, standing watching with hands on hips. In accordance with actual events, Clark inserts an explosion hitting the ship itself, depicts the anti aircraft gun in the bow in action, and shows figures running around in the foreground as a truck is driven down the ship’s ramp. The bombardment of the ship by the Japanese occurred while the ship was landing on Mono Island on 27 October however, not Stirling.

Clark has used the photograph as a starting point to create a synthesis of events surrounding the invasion of the Treasury Islands. It is not an accurate historical record of what occurred. It is also interesting to note that there are no American soldiers in Clark’s painting, even though they appear in the original photograph. Clark, and presumably the NZ Army, wanted to emphasise that this was primarily a Kiwi operation.

A more thorough analysis of the circumstances behind this work is presented in the section about “Migration of War Art Imagery”.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

Thirdly, the attitude of the defense bureaucracy appears to be that significant events in military history are more effectively recorded in the traditional medium of oil paint, to foster a greater sense of gravitas and permanence that results from the nature of the medium itself. War offers a traditional “realistic” artist a wonderful opportunity demonstrate his skill to create a sense of drama, action and excitement, as well as the chance to represent exotic cloud and landscapes, explosions and swirling smoke, as in the painting of the Duke of Wellington at Waterloo by Robert Alexander Hillingford (Figure 4).

So, what is the role of official war artists (nowadays apparently designated “official recorders”) in the age of photography, video and satellite phones? Indeed, in the era of mobile phones and drones, the role of official war artist appears to become ever more anachronistic and untenable.

In her book “War Correspondent: Reporting under fire since 1850”, Jean Hood says “The answer may be that a photograph is valid as a frozen moment: a painting or drawing, by contrast, is an impression, an interpretation, mediated by the human imagination and offering a complementary account of one of mankind’s oldest impulses.”

As discussed elsewhere in this website, that way lies the potential for propaganda…