Maurice Conly (1920 – 1995) was born in Dunedin (Figure 1). He displayed considerable artistic talent at a young age, which he was encouraged to develop by his parents. In 1933 he won the primary schools section of the Dunedin Horticultural Society’s painting competition with a painting of a daffodil. The prize was presented to him by Russell Clark. They were to become friends in later years, and both were to become official Pacific war artists.

He continued his art training at the highly respected Dunedin School of Art, a department of the King Edward Technical College in Dunedin. His teachers there there by William Henry Allen and Robert Nettleton Field, two Royal College of Art graduates who had emigrated to New Zealand as part of the La Trobe Scheme, a program which had been established by the government in the 1920s in order to attract established artists from Britain to teach in New Zealand schools, to foster greater professionalism in the training of artists.

On leaving the art school, Conly was able to get a position at the Dunedin publishing firm of Coulls Somerville Wilkie (later to become the publishing company and book-store chain Whitcoulls) as a junior artist, where he received valuable training in the graphic design and printing industry.

Conly joined the Royal New Zealand Air Force in February 1941. He was sent to the RNZAF Station at Levin near Wellington for training. While making a rapid descent on a training flight in a de Havilland Tiger Moth Conly’s eardrums were ruptured. After an unsuccessful operation to correct the condition he was declared medically unfit to fly and his piloting career came to an abrupt end. During his convalescence period Conly approached the offices of “Contact” magazine, a new publication by the RNZAF’s public relations department, seeking a position as illustrator.

His skills were recognised and he was offered a job as artist with the magazine. Conly’s illustrations were to become regular features on the cover, his first appearing in December 1941. It was an illustration of the then radically new Lockheed P38 Lightning. The P38 was not flown by the RNZAF but it became a popular aircraft with the Americans in the Pacific and large numbers were sent to Britain. Conly has shown the plane in RAF markings (Figure 2).

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

Part of Conly’s early duties were to make drawings of the Airfield Defense Units being set up around New Zealand airfields as a result of the growing threat from Japan, particularly in the north of the country, the closest point to Japan. We can but wonder if his decision to show the machine gun apparently aimed directly at the sentry’s head in the drawing in Figure 3 was a conscious one to increase tension, or if Conly was not aware of this unfortunate effect…

He was also given the task of designing advertising and recruitment posters for the RNZAF (Figure 4).

Conly was supplied with the latest flying magazines by the United States Information Service in Auckland, which contained photographs and drawings of the latest types of aircraft from which he created his illustrations. He made drawings recording the various aircraft types appearing for the first time at New Zealand airfields, which were often used as the basis for later full scale paintings.

Conly developed his characteristic pencil and conte crayon technique for these drawings, which he continued to refine throughout his career (Figure 5). He concentrated on aircraft flown by New Zealand pilots, sketching or painting from photographs and adding backgrounds to re-contextualise and add action or drama (Figure 6). He also used his conte and pencil technique for the many official portraits he was required to complete, such as the example below of Wing Commander Desmond James Scott, one of New Zealand’s most decorated fighter pilots in World War II (Figure 7). This technique appears to have been Conly’s forte and he produced many such portraits during his time in the RNZAF.

It was common to adapt photographs of aircraft and other images for the purposes of re-contexturalising them in a painting and artists of the time felt free to do this. There were no reservations about crediting or intellectual property at the time: even if there were, they would have probably been dismissed by the artist and audience alike in the interests of a higher calling of inspiring and morale building during a time of war and national survival.

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

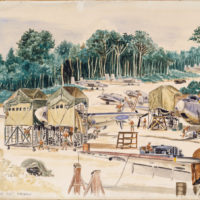

Conly visited Guadalcanal, Florida Island and Emirau Island at the end of 1944, working alongside Russell Clark. He produced many drawings in pencil and conte as well as water-colour paintings of the New Zealand facilities at Henderson Field, where the RNZAF operated Kittyhawk and Corsair fighters and Hudson and Ventura bombers. He visited the No. 6 Catalina Flying Boat Squadron Base at Halvo Bay on Florida Island, on the northern side of Iron Bottom Sound from Guadalcanal (Figure 8), as well as Bougainville Island (Vanuatu) and the island of Los Negros.

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

During his visits to the air force bases Conly recorded ongoing repairs and maintenance of aircraft, the daily lives of the air force servicemen and officers, as well as local scenes and buildings. He made many formal portraits of RNZAF officers in pencil and conte, but does not appear to have made many final paintings from them. He was not a strong figure artist and his main strengths were in making illustrations of aircraft, whether being maintained on the ground, in flight, or sometimes in imagined combat (Figure 9).

Conly clearly had a love affair with flight and aircraft technology and many of his paintings depict servicemen doing maintenance on aeroplanes, a theme that appears to have fascinated him (Figure 10). While the painting has historical importance in recording the working and maintenance operations of the airfield at Emirau, Conly seems to struggle with getting perspective, scale and viewpoint correct. There is a strange, flattened out quality to the picture, with the viewpoint of the aircraft in the foreground seemingly lower than the airstrip in the background. Our viewpoint is higher than the aircraft yet we see the underside of its wing. The truck seems to be driving up-hill in relation to what appear to be P38 fighter-planes lined up in the middle distance, not a likely scenario on a flat airstrip.

The planes in the picture were cutting-edge combat aircraft representing the latest in aviation technology in 1944. That they required ongoing specialist servicing seems to have intrigued Conly as a symbol of the emerging new technological age, especially as it inevitably impacted on the simple lifestyles of the Pacific Islanders. Similarly, Russell Clark and other artists represented LSTs being unloaded on pristine beaches as a metaphor for a twentieth century technologically advanced culture colliding with what was popularly perceived as the exotic traditional cultures of the Pacific.

Conly appears to have worked frequently from photographs. Composite pictures were a common device among official and unofficial artists, especially when the subject matter was aircraft in action. In the hands of a skillful artist like Russell Clarke, the effect could be totally illusionistic and convincing. Sometimes however the technique created an unreal effect when the two or more views did not quite match up, as in this Conly painting of a downed pilot being rescued by a Catalina PBY flying boat (Figure 11). While historically and geographically accurate (the land forms on the horizon appear to be Savo Island) the over-flying Corsairs are clearly out of scale and difficult for the eye to place in relation to the man in the life-raft and the flying boat in the background. The slightly downward angle the lower plane is flying at appears to put it in imminent danger of crashing into the sea.

The more spontaneous nature of Conly’s conte observational drawings of the places he visited, a style he had developed earlier in New Zealand, provide a genuine insight into the daily lifestyles of the servicemen of the RNZAF and occasionally the local people. These are more direct and engaging representations of the sites and scenes Conly witnessed and are arguably more historically poignant than the more “finished” formal paintings that he created.

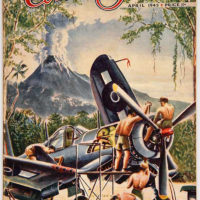

Soon after he returned to New Zealand in 1945, Contact magazine was closed and Conly was discharged from the Air Force. One of his last wartime cover illustrations for the magazine was a 1945 painting of one of his favourite subjects: men at work servicing a Corsair fighter plane, complete with imaginary volcano in the background (Figure 12).

He worked for a time as Art Director with a Wellington advertising agency before returning to a position at the publishers Coulls Somerville Wilkie in Dunedin, where he was charged with setting up a creative art department.

Conly returned to the RNZAF as its Official Artist in 1954, following the relaunching of Contact magazine in 1952. He received a commission and was promoted to Flight Lieutenant in 1959.

Conly continued to record the personnel, facilities and activities of the RNZAF, in Fiji in 1965 and Vietnam in 1969. In 1971 he flew to New Zealand’s Scott Base in Antarctica to record the activities of No. 40 Squadron RNZAF during their annual operation to the ice.

From 1955 until he died in 1995, Conly was New Zealand’s chief stamp designer (Figure 13).

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

He also designed the New Zealand 20c and $1 coins (Figure 12). The latter was introduced in 1991, four years before his death, to replace the paper denomination. The 20c coin was withdrawn at the same time, but the latter is still current, an enduring testament to an important New Zealand artist that lives on in most New Zealanders’ wallets and purses today.