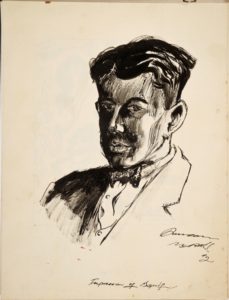

From the large collection of his work in the New Zealand Archives, which includes a self portrait (Figure 1), it is clear that Duncan McPhee was a prolific artist who worked mostly in pencil, Indian ink and watercolour. His forte was as a cartoonist and caricaturist.

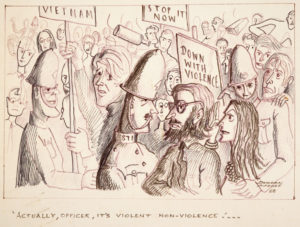

There is little information available on the life and wartime experience of McPhee. It is possible however to piece together a little of his history through the extensive amount of art that he left behind: from the information included on his drawings, it is clear that he was in Guadalcanal, Tulagi and Bougainville, and returned to New Zealand at the end of the war. He was working until at least the late 1960s, as evidenced by his drawing of a Vietnam War demonstration from 1968 (Figure 2).

A love of art and drawing was clearly a major part of McPhee’s personality. While on active service in the Pacific it appears that he encouraged others to get out and record their surroundings and seems to have formed friendships with servicemen who enjoyed expressing their creativity in this way. Several of McPhee’s works depict fellow artists, sometimes working with drawing boards and easels in the open air in what appear to be joint field trips to various locations around Guadalcanal.

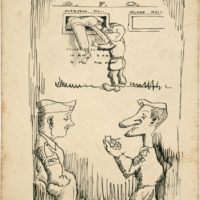

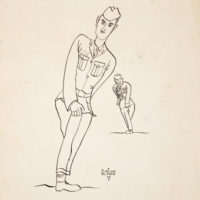

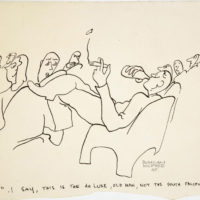

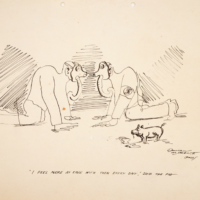

His drawings often poke gentle fun at military and political leaders and institutions. Many of his cartoons have a gently satirical, almost Pythonesque quality (Figures 3 – 5). Most of his visual barbs were aimed at the New Zealand army but sometimes he lampooned the Americans too (Figure 3).

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

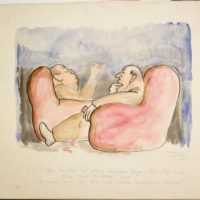

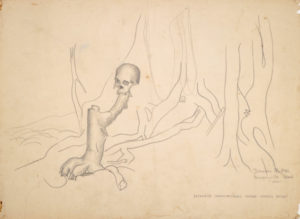

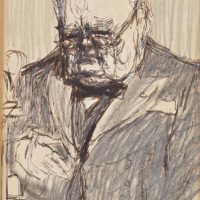

At times his work transcends satire to become pointed attacks on politicians and war-mongers (Figure 6), what McPhee perceived as the public living comfortable lives back Home (Figure 7), and the brutal insanity of war in general (Figure 8 and 9).

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

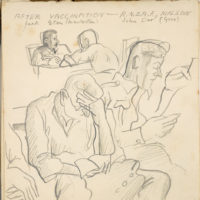

McPhee was an astute observer of daily life in the army and must have drawn constantly. Many mundane aspects of life in the army and airforce were spontaneously recorded in pencil, pen and wash, from doing the laundry (Figure 10), to playing poker (Figure 11), to enduring the dreaded vaccinations, where he identifies the characters in the picture by name (Figure 12). (A dread of vaccination crops up in many accounts of being inducted into the armed forces in World War Two: perhaps the needles were a lot thicker and blunter, the experience much more unpleasant in those days. For most of these young men, this would have been their first encounter with “the jab”, unlike the modern experience, with inoculations being for most people an integral part of growing up.)

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

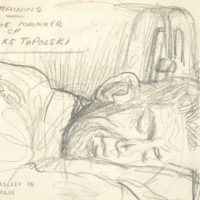

McPhee admired and adapted the drawing style of Polish artist Feliks Topolski (Figure 13) and gives an acknowledgement in his depiction of a sleeping airman on a train (Figure 14), most likely done in New Zealand rather than the Solomons, since there are to this day no trains there or in New Caledonia.

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

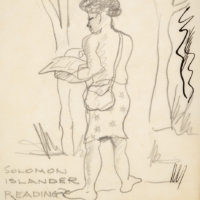

He was keenly interested in the lives of the local Melanesian people and made many studies of them engaged in daily activities (Figure 15). He was also moved by the range of physiognomical types he observed (Figure 16). He must have been struck by the incongruity he saw in the clash between the local culture and those of the invading foreign forces, epitomised in his drawing of a native man reading a discarded “Life” magazine (Figure 17).

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

Like other soldier artists in the Pacific Theatre, McPhee appears to have been impressed by the surreal effects created by this clash of cultures, as first the Japanese and then the Allied military machines overwhelmed the simple lifestyles and pristine landscape of the Solomon Islands.

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

- Figure 20

The wrecked Japanese landing barge (Figure 18) has a distinctly Surrealist flavour in the soft treatment of form and sketchy colour as well as the juxtaposition of imagery created by the destroyed war machinery with the tropical beach and distant coconut trees. The distorted landscape is reminiscent of Salvadore Dali’s 1931 painting “Persistence of Memory” (Figure 19). McPhee used a similar watercolour technique to his image of the wrecked Japanese barge in his “Banyan, Hill 260, Bougainville” (Figure 20).

A centralised composition and elevated viewpoint contribute to another disturbing McPhee image, a drawing of two blimps being inflated near a beach on point Cruz in Guadalcanal (Figure 21). Without the note explaining the context included with the drawing, it would be difficult to comprehend exactly what is happening in this image. Two huge amorphous forms lay next to blasted coconut trees and what appear to be a stack of gas cylinders. The shapes in the centre of the frame appear as two giant pupae or maggots with an implicit life of their own, overwhelming and threatening the diminutive figure in the foreground. (Adding a personal layer of strangeness is the location: Point Cruz is a small outcrop of land in the middle of Honiara, right next to the Mendana Hotel that I stayed in during my visit in 2010.)

McPhee’s many drawings serve as a visual diary of his journey in the New Zealand Army, and a fascinating historical record of New Zealand servicemen’s involvement in the Pacific War.

While they may not have much in the way of biographical information about McPhee, the National Archives has a substantial collection of his drawings and water colour paintings on its website:

http://warart.archives.govt.nz/DuncanMcPhee