Two dimensional works, especially pencil drawings, were understandably the most common medium under the harsh tropical circumstances. HB pencils and drawing paper were easily obtained and in a moment of boredom a serviceman might decide on a whim to record his surroundings. Or he might go out to a particular landscape with several like-minded others to try his hand at observational sketches in pencil or conte crayon or possibly even watercolour (Figure 1). (As mentioned elsewhere in the website, oil paints were rarely used in the tropics because the tubes tended to leak and burst in the heat.)

The creators of drawings and other works on paper are more likely to be identifiable than the makers of three-dimensional artworks, because of the age-old convention of signing and dating work, and because it was a simple matter to record such details in the corner of the frame, or sometimes on the back of the work.

Often a work will be dated and signed, but the name of the individual now means nothing: his identity, and the provenance of his work, long ago lost. In this sense, the artist is as effectively anonymous as if the work had no name inscribed on it. In such cases it is fair to describe such artists as “Semi-Anonymous”.

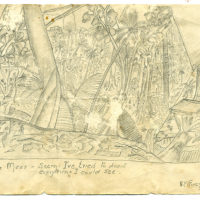

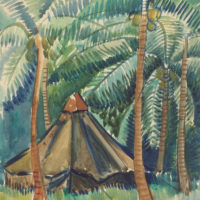

It was often the case that a soldier would produce only one or two drawings and not bother to continue to develop his craft any further. Sometimes a single drawing will demonstrate genuine undeveloped talent, as in the carefully detailed work by Harry Stones’s Commanding Officer, Major Robert “Bruiser” Foreman, showing the view from his tent on Mono Island (Figure 2). He captions his drawing: “What a mess – seems I’ve tried to draw everything I could see.”

One can only speculate at the circumstances that lead to Foreman making this drawing. It is likely he was laying on his bunk on a hot afternoon, nothing to do, and decided spontaneously to pick up his pencil and record the scene before him, as a memento to take home to show his family.

The drawing is indeed rich in detail, carefully rendered with Foreman’s pencil. He has attempted to record the variety of jungle foliage before him in detail, including the evidence of trees felled to make way for the campsite. On the left, just outside Foreman’s tent, there appears to be a muslin covered “food-safe”, suspended on a cord, to protect consumables from insects and rodents. A wooden duckboard leads the eye across the front of the tent into the jungle. A second army tent is set up on the right of frame, together with a clothesline and washing hung out too dry. A tent flap is tied to a log in front of the entrance. It is a peaceful scene; the war had moved on, and the 8th Brigade had about six months until they departed for Home.

- Figure 2

- Figure 9

Indian ink drawings and wash and watercolour paintings were also quite popular two-dimensional media, and many seemed to have preferred these to pencil.

For the young soldiers, who had in most cases never travelled overseas before, the exotic tropical vegetation and landscapes they found themselves in, as well as the native islanders they encountered, so different from what they experienced at home, also provided the motivation to visually record their surroundings in some form. With cameras banned by the authorities, what better way to document their new experiences than with pencil and paper?

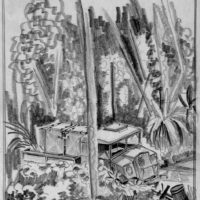

On the evidence contained in one of his many skilfully toned pencil drawings (Figure 3), it appears Arthur Owen “Polly” Pollock, a Sergeant attached to the 7th Field Ambulance, was based on Mono Island. He is recorded on the Auckland Museum’s Cenotaph site as being from Napier, where he was apparently a window dresser before the war. He produced many drawings during his time in the Pacific, but while one of his drawings depicts the Field Ambulance base being on Mono (Figure 4), another shows his “Home” being on Stirling Island (Figure 5). The drawing in Figure 4 shows the RAP (Regimental Aid Post), on Mono Island, which is presumably where Pollock was based. (The Regimental Aid Post is a front-line military medical establishment incorporated into an infantry battalion or armoured regiment for the immediate treatment and triage of battlefield casualties, but also the treatment of general medical issues such as accidental injuries, insect and snake bites. In the US forces, the equivalent is the Battalion Aid Station.)

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

Many of Pollock’s drawings, like so many made by other artists, document the daily activities and setup of his medical unit, whether it be a mosquito spray unit such as the Ford 4×4 truck with spray tanks on the tray in Figure 6, or an ambulance going about its business in Figure 7.

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

However, another strand in his drawings takes a more fantastical direction, where he appears to synthesise a composition from several different sources. The indian ink wash drawing of the PBY Catalina moored in a logoon is an example (Figure 8). Like the Pollock image included in this website’s section on “Migration of Imagery”, the aircraft does not quite seem to be part of the scene: it is difficult for the viewer to discern whether it is flying close to the water or is anchored at rest in it.

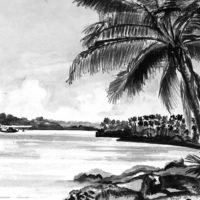

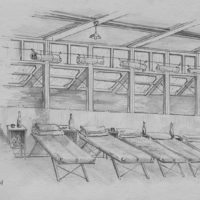

Graham Clarence Park was another artist who produced a solid collection of pencil drawings. Like Pollock, very little is known about Park. According to Auckland Museum’s Cenotaph entry on Park, he lived in Palmerston North at the time he enlisted. The Cenotaph website records that he was an artilleryman: one of his cartoons mentions the 38th Field Regiment. Like Pollock, he appears to have held the rank of Sergeant.

Before he enlisted, Park had been a trained draughtsman, although the record does not indicate whether he was working as such at the time. This perhaps explains the precision and discipline evidenced in some of his work, such as the drawing of the row of bunks in the barracks in Figure 9, with its careful attention to double point perspective and everything neatly laid out as if for inspection. Clearly Park was a man who appreciated tidiness.

At other times his drawing was looser, more impressionistic. He drew the human figure rarely and does not appear confident doing so. The charming depiction of a man having a shower, awkwardly covering himself as if embarrassed by the artist’s presence (Figure 9), was drawn in October 1943, which suggests that it might have been created in Guadalcanal, since the invasion of the Treasuries did not take place until October 28.

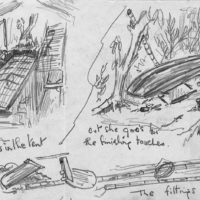

The loose thumbnail sketches of a boat being built – “She starts in the tent…Out she goes for the finishing touches…The fittings arrive” – could have been observational notes for a later work, perhaps in another medium, and are dated 1943 (Figure 11). This is more likely to have been drawn on Mono or Stirling Island.

Many of the men tried their hand at boat building when the Japanese had been driven off and things had settled down in November and December. Oscar Kendall depicted a group of men working on a dugout canoe on December 2 1943.

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

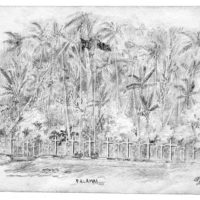

It is interesting to compare Park’s drawing of the Allied Services Cemetery at Falamai (Figure 12) with Raymond Starr’s recording of the same place (Figure 13). Park’s version is flatter, more two dimensional. The row of crosses blend in the the precisely rendered jungle foliage in the background. Almost lost amongst the vegetation are the two flagpoles with the Stars and Stripes and New Zealand flag fluttering above. The pattern-like treatment of the scene creates a more abstracted image than Starr’s composition. Interestingly, both drawings were made in January 1944, which begs the question of whether the two men knew each other: perhaps they had gone out together to draw the cemetery.

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

There are many other singular examples of “semi-anonymous” artists working in two dimensions in private and public collections, about whom we know even less than the two artists whose work is recorded above. Their work is often of such high quality that one naturally wonders who these men were and whether there are other examples of their work tucked away in family documents that may never see the light of day.

The monochromatic wash in Figure 14 is by a soldier identified by Auckland Museum Cenotaph as Linwood Anthony Lipanovic, who lived in Mount Albert, Auckland. He was a Sergeant and belonged to a camouflage unit, and also worked for the Current Affairs branch of the Army Education and Welfare Services (A.E.W.S.). He was a painter and decorator in private life. The painting appears to show the reconstruction, by New Zealand soldiers, of the church that was shelled during the invasion of Mono Island. It was being used as an ammunition dump by the Japanese (Figure 14). Oscar Kendall also made a watercolour painting of the church under construction (refer to website section on Oscar Kendall).

According to Archives New Zealand, where this painting presently resides, the delicately painted watercolour in Figure 15 is by M. Jillet and depicts the “Enemy bombing of Melanesian Cathedral”. Although there is no indication of where the cathedral was located, it appears to be St Lukes on the island of Nggela, north of Guadalcanal. According to the Solomon Islands Historical Encylopaedia website the Anglican cathedral of St. Lukes, built at Siota in 1920s, was “badly damaged” in the war. (The website also claims that servicemen helped themselves to artefacts from the cathedral as souvenirs.) The Auckland Museum Cenotaph website shows the artist’s full name to be Moss David Jillet. He was a Private soldier from Wellington.

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

The painting of a native man seated on the base of a coconut tree in Figure 16, signed R. Jack Hutchison, is by Richard Jack Hutchison, who was from Christchurch at the time of his enlisting. It depicts an iconic Pacific Island scene that belies the impact of war in the Solomons at the time. The brightly coloured, naively painted image gives us an informative record of the lifestyle of the native Solomon Islanders. The native man, rather awkwardly painted, sits on the left of the frame, a substantial thatched building behind him on the right. Coconut trees frame a lagoon in the background.The war does not intrude on this delightfully rendered scene, which could have been made yesterday rather than during the War in the Pacific.

We know a little more about Hutchison than the other two artists, thanks to research work by his niece Prue Theobald posted on the Auckland Museum Cenotaph website. Jack belonged to the Dental Corp and held the rank of Corporal. The Auckland Art Gallery has a collection of his paintings:

A beautifully and perhaps more skilfully executed watercolour painting shows another kind of idealisation: a pristine Jeep being driven by an immaculately uniformed New Zealand soldier, made by Charles Winton Bristow (Figure 17). Bristow was from Herne Bay in Auckland and a Private. Like Harry Stone, he was a gunner, but rather than being in an anti-tank unit, he was with the New Zealand Artillery.

Perhaps, given the exquisite rendering and idyllic portrayal of the subject, including the ground level viewpoint and pristine condition of the vehicle, it is no surprise to discover from the Cenotaph website that Bristow was a commercial artist by profession. The image has the appearance of being made for an advertising campaign for Jeep. Perhaps it was made in the relative peacefulness of New Caledonia before Bristow moved on to the Solomon Islands? The foliage behind the Jeep would seem to confirm this. The harsh reality of service for a Jeep on Guadalcanal or anywhere else in the Solomons was somewhat different (Figure 18).

- Figure 17

- Figure 18

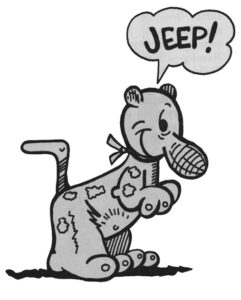

It is interesting to note in passing the origins of the name of this most versatile and resilient of WW2 vehicles. The most common impression is that it is a contraction of the term “General Purpose vehicle” – GP – and this is a good indicator of its primary role. However, according to a Readers Digest compendium of interesting facts published in the 1970s, the name originally came from a “part dog, and wholly fantasy” character created in 1937 by the American cartoonist E. C. (Elzie Crisler) Segar (Figure 19): “Jeeps, according to the strip, were tough little animals who lived on orchids and could become invisible. When…the Willys company of Ohio won a US Army transport contract with a powerful open-topped 4-seater vehicle that was just over 3m long and could go anywhere, soldiers gave the rugged little machine the same name.” – “Strange Stories and Amazing Facts”, Readers Digest Association, second edition, 1975.

According to Wikipedia, Eugene the Jeep was a character in the “Popeye the Sailor” comic strip, which was created by Segar.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eugene_the_Jeep

Sometimes it is simply impossible to track down any information about an artist, even when you have a name to work with. For example, the pencil and conte drawing of what appears to be, from the evidence of the nurse’s uniforms, the New Zealand hospital in New Caledonia (Figure 20). We know that it was painted by Herold Brocklebank Herbert: beyond that, nothing. His name does not appear on the Cenotaph website.

Occasionally, an artist’s work turns up which is so skilful that it is almost beyond belief that there is no record at all of who he was or anything about him beyond where the images were made.

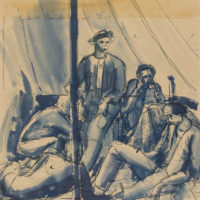

The works below (Figures 21 – 23, 24 and 25) are by the same artist but are completely anonymous. On every one of these works, presently in the Colin Moyle collection at the Auckland Museum, the artist has recorded that it was made on the Island of Espiritu Santo (the artist mistakenly spells the name of the island Espirito Santo, which is actually an area in Brazil), the largest island in what is now known as the island nation of Vanuatu, in the last year of the war, but has signed none of them. This island was not invaded by the Japanese but it was an American naval and air force base for much of the war. None of this artist’s works is signed. Frustratingly, the location and often the date of each has been recorded, but nothing else.

- Figure 21

- Figure 22

- Figure 23

Like many other soldier artworks in World War 2, these images provide us with an intimate record of, and insight into, the life of servicemen during their relaxation and off-duty time. From the evidence of the works included here it is clear that the artist was highly skilled in watercolour, wash and brush and ink media.

- Figure 24

- Figure 25

Cartoons: Humour in New Zealand soldier art in the Pacific War, often sardonic, took many forms and was a good antidote to general boredom, homesickness and resistance to, if not outright contempt for, the army, officers and general bureaucracy. Cartoons could be hand-drawn for sharing within a soldier’s particular unit or made for reproduction in service newspapers or magazines.

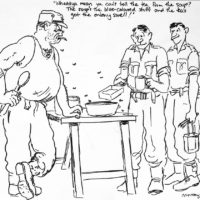

Frequent subjects in cartoons are “the soldier’s lot”, including his putative low intelligence, often in the face of authority and army discipline, the confrontation between men and their superiors, or dreams of the life at home that they were missing. Sometimes crudely drawn, the images often had an earthy “made by one of the blokes” quality that must have further endeared them to their audience.

In the first set of cartoons by a man we only know as S. Jones, a private soldier has volunteered to wait on the sergeants’ mess and is regarded as therefore having lost his mind (Figure 26): his mate and the officer sitting at the typewriter recoil in horror, while a parrot sitting on a perch in the background shrieks “Tropo (i.e. tropical: mad)! Tropo! The poor (bastard’s) Tropo!”

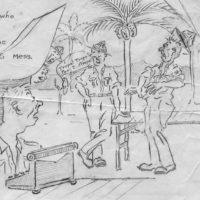

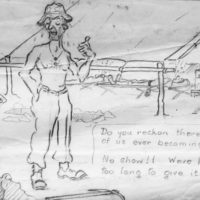

Officers were often the target of such derogatory drawings. In the second drawing by Jones (Figure 27), one soldier says to his mate: “Do you reckon there’s a chance of us ever becoming officers Bert?”, to which Bert replies “No show!! We’ve been working too long to give it up now.” The implication is that the officers’ lot is an easy and comfortable one compared to that of the common foot soldier.

- Figure 26

- Figure 27

- Figure 28

In the third drawing, a sleeping soldier dreams of rows of bottles of beer, roast turkey and Christmas pudding and, most importantly of all, projecting from an imaginary Christmas stocking, his discharge papers (Figure 28). It is likely that this drawing was produced to mark Christmas 1943.

In one of the few drawings with a signature (S. Jones C Company) the hoary subject of large, ferocious tropical mosquitoes is taken on, with a soldier firing his rifle at one of the giant insects as his mate beats a retreat on the left of frame (Figure 29).

‘A Yankee officer told us a “gag” about the mosquitoes back in his home state. At a camp there, two “mossies” were heard talking. One said, “Shall we eat this guy here, or carry him across the lake?” But the other “mossie” answered, “If we take him over there, the big ones will get him!”‘ – Harry Stone, New Caledonia, Diary No. 1, Wednesday 10 March 1943

Why did S. Jones make these cartoons? And who was S. Jones? We don’t know the answer to either question, but it is likely the drawings were made simply to fill the time and were shown to the soldier’s mates and sent home to family.

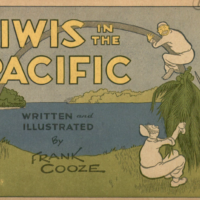

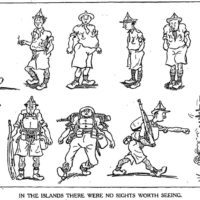

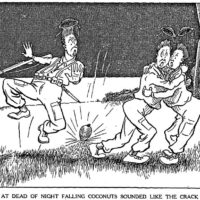

Cartoon drawings sending up life in the services could sometimes form the basis of small publications such as Frank Ivan Cooze’s “Kiwis in the Pacific” (Figures 30 – 32), which was printed in New Zealand on his return from the islands. The captions beneath the cartoons are written in the past tense, reinforcing that Cooze is reviewing his Army experiences from the perspective of the returned soldier. Cooze released another book in 1946 called “My Little State Home in Suburbia”.

- Figure 30

- Figure 31

- Figure 32

Another interesting army cartoonist was Murray Moorhead. Moorhead was born in New Plymouth 1934: too late to participate in WW2, he was called up for Compulsory Military Training in 1952 and, like Harry Stone, was trained on 6-pounder anti-tank guns. He remained in the Territorial Army until 1967 when he retired with the rank of Staff Sergeant.

According to the New Zealand Army website, “Moorhead had many books and cartoons published during his lifetime and was awarded the New Zealand Military Historical Society’s Literary Award in 1987. His last book First in Arms published in 2004 told of the experiences of the Taranaki Rifle Volunteers during the Taranaki War of 1860 – 1861.”

What makes his army cartoons particularly interesting, apart from the acerbic humour many of which project a quite negative impression of institutionalised army life and culture, is the fact that, despite not serving at the time of WW2, so many are of his images are based on the Pacific War.

Amongst the collection of pen and ink and watercolour works by Moorhead, housed at the Army Museum in Waiouru, there are ink-wash and water-colour paintings which appear to have had their origins in photographs from the war in the Pacific, including soldiers on patrol, a Ford 4×4 truck (a vehicle surely designed for maximum ugliness as much as for practical utility), and an anti-tank shoot reminiscent of the photograph of Harry Stone’s unit during a practice shoot on Stirling Island at the beginning of 1944 (Figures 33 – 35).

- Figure 33

- Figure 34

- Figure 35

There is also a small watercolour of wounded soldiers being unloaded from a landing craft which is very similar to Russell Clark’s work of wounded being unloaded on Stirling Island, itself based on a photograph (Figure 36 and 37).

- Figure 36

- Figure 37

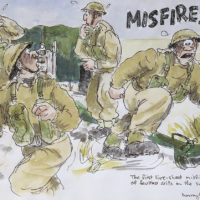

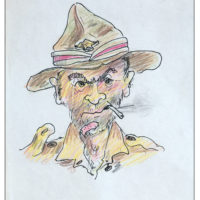

Many of Moorhead’s cartoons draw on the army cartoonist’s tradition of sending up incompetent officers and half-witted conscripts who just want out of the army (Figures 38 – 40).

- Figure 38

- Figure 39

- Figure 40

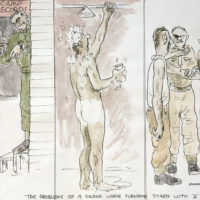

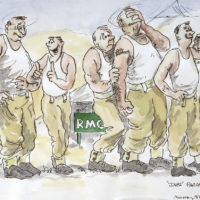

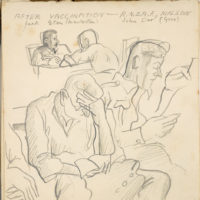

Army routines are up for lampooning, such as queuing to take a shower (Figure 41). Like Duncan McPhee, Moorhead comments on vaccinations: Moorhead portrays the procedure doled out at the R.M.C. (Regimental Medical Corps) as one giving rise to dread, swooning and fainting-fits among grown (and decidedly unfit looking) “fighting men” (Figure 42), while McPhee, in contrast, shows men quietly recovering after having their shots (Figure 43).

- Figure 41

- Figure 42

- Figure 43

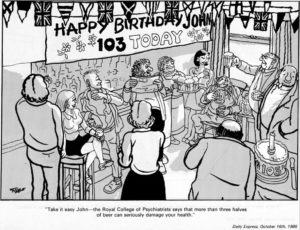

Stylistically, as well as in their form of depredating humour, Moorhead’s cartoons were very similar to the British Daily Express cartoonist Ronald Giles, who made a very successful career out of ridiculing British class-based lifestyle and generational contrasts (Figure 44). As with “Giles”, who was a very popular and extremely well paid cartoonist working from the mid-1950s (1955 he was earning the equivalent of almost $NZ500,000 a year creating three cartoons a week for the Daily Express) until the end of the 1980s, an important characteristic of Moorhead’s cartoons was that the image depended heavily on the accompanying caption to make its point: without the caption, the cartoon often lost its meaning.

Decorated Envelopes: A particular art-form that seems to be unique to World War 2 is the decorated envelope. Mail delivery was reasonably frequent and swift in the Pacific in both directions: from and to home. The positive effects on morale of receiving regular news from home for the troops, as well as for those at home receiving confirmation that all was well for loved-ones overseas, was well recognised by the authorities. Family news kept the men in touch as well as providing a much needed relief from boredom and the ongoing sense of isolation.

Conversely, not receiving mail for a soldier could be very upsetting. If mail was delayed for any reason it could be a signal that something was not right at home. Harry Stone vents his frustration at not hearing from his new wife back in New Zealand on several occasions in his diaries when the latest air delivery did not contain an expected letter from her.

(Stone Harry was a prolific writer at the time, and in addition to writing up his diaries every day he was overseas, he sent many letters to my mother Adele. Tragically, when he died in 1975, she spent an afternoon burning them in the living room fireplace. When I asked her why she had done that, she replied that they were too personal for anybody else to see: understandable from her perspective. I suspect this was a common occurrence amongst war widows, both during the war and in the years following, but they were literally reducing history to ashes.)

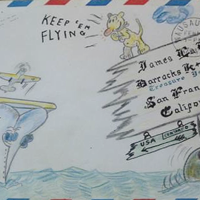

To customise the standard mail envelope (and again, probably to fill in time), some men would devote hours to applying their drawing skills to the outside of the envelope, transforming them into miniature cartoon artworks in their own right. It is perhaps a testament to the care and efficiency of the armed services mail system that so many of them got delivered to their destinations undamaged or were not stolen in transit.

This art-form was not a feature of just New Zealand servicemen, or even just Pacific War servicemen. Decorated envelopes appeared in correspondence from troops stationed in most overseas areas of conflict to family and friends at home. The practise seems to have been especially common amongst American soldiers in the Pacific, possibly because the popular image of life in the South Seas lent itself to lighthearted comic strip imagery.

Pacific illustrated envelopes were often characterised by racial and cultural stereotypes and cliches. These anonymous American examples (Figures 45 and 46) show two variations, sent to different addresses in the US, on the Pacific Islander cannibalism theme popular in cartoon books and comic strips at the time (surprisingly, the artist appears to be under the illusion that giraffes are part of Pacific Islands wildlife). The similarities in detail and composition of the two drawings suggest that tracing paper was involved as part of the creative process.

In both drawings, a fat island chief sits smoking a cigar, while a hapless GI soldier stews in a large cooking pot, supervised by a European-looking, perhaps French, kitchen chef brandishing a stirring spoon and large knife. Skull and bones from previous meals, as well as salt and pepper shakers, litter the foreground. A puzzled turtle looks on.

- Figure 45

- Figure 46

This envelope artist clearly had a liking for George Herriman’s “Krazy Kat”, an idiosyncratic American newspaper comic strip which ran from 1913 until 1944 (Figure 47). He has used his adaptation of the image of Krazy Kat as a visual linking device and commentator in Figure 45 and 46.

The third example by this artist depicts an aircraft carrier with a fighter plane being launched from its deck and the exhortation to “Keep ’em flying” from the Krazy Kat lookalike (Figure 48).

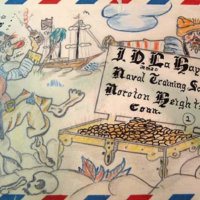

The rum-swigging, treasure-chest toting pirate cliche is the basis for Figure 49, although historically pirates are associated with the Atlantic and Caribbean more than the Pacific.

- Figure 48

- Figure 49

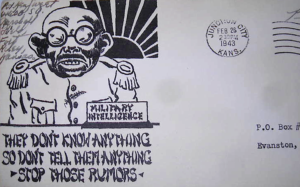

A fifth anonymous American example, although it originated in Kansas rather than the Pacific, features a racially unflattering portrayal of the Japanese general and wartime Prime Minister Hideki Tojo (Figure 50), and a warning against spreading rumours that might assist the Japanese war effort.

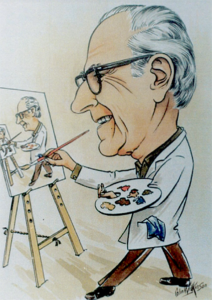

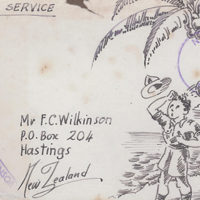

One of the most prolific New Zealand envelope soldier-artists whose work has survived was Colin Wilkinson (1914 – 2004) (Figure 51), who was a Corporal in the 34th Infantry Battalion. Wilkinson grew up in Havelock North and soon after leaving school began work for Cliff Press printers in Hastings and subsequently for Pictorial Publications in Hastings as Art Director. He continued to work as an amateur artist after the war and exhibited work at the Havelock North Community Centre.

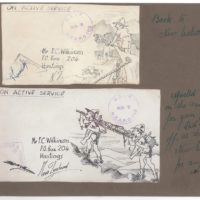

Wilkinson produced dozens of personalised envelopes which were sent home to his family in Hastings. These have been loving preserved in an album, some alongside notes which explain the context of the artwork (Figure 52 – 54).

- Figure 52

- Figure 53

- Figure 54

Wilkinson was a skilled cartoonist and many of his delightfully lighthearted drawings (Figure 55) have about them something of the flavour of Belgian cartoonist Georges (“Herge”) Remi’s “Tintin” comics(Figure 56), which were becoming popular in New Zealand in the years before the war. The first Tintin comic book appeared in 1929.

- Figure 55

- Figure 56

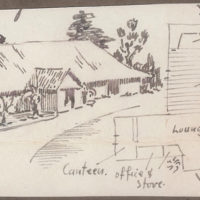

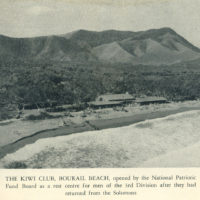

There is little information available about where Wilkinson served during the war. His service record states “IP” (In Pacific) but, typically for army records at the time, does not give details. It is likely that as a member of the 34th Battalion he participated in the invasion of Mono Island on October 27 1943. None of the images he produced, with the exception of the Kiwi Club building on the beachfront at Bourail in New Caledonia (Figures 57 and 58), were of specific places, probably for censorship reasons.

- Figure 57

- Figure 58

Wilkinson continued to make art right up until he died in 2004, but for many servicemen after the war, producing artworks of any kind was, understandably, dismissed as a frivolous activity, as they set about rebuilding their lives, finding work, reuniting with wives and pre-war sweethearts, and beginning their “baby boomer” families. The photograph shows Wilson, in uniform, either before leaving for the islands or soon after his return, with his wife Cora (Figure 59).

Making art had been a marker of a particular part of the servicemen’s lives, which most wished to now put out of their minds. Making images and models had been a preoccupation then, under the extraordinary circumstances they had found themselves in, but now there were more important things to be getting on with…