Oscar John Kendall is an artist of whom we know almost nothing, other than that he was born in London in 1909 and apparently died in 1969. We also know that he was a private in the 29th Battalion and grew up in Onehunga, Auckland. He exhibited several works in the “New Zealand Artists in Uniform” exhibition in 1944, and produced a book of wartime cartoons and caricatures called “Playboys of the Pacific”.

It has not been possible to find any photographs, portraits or self-portraits of Kendall. In fact it is difficult to discover any information on him at all. This is unfortunate because Kendall was a highly talented and prolific artist who, on the evidence of his works, clearly served in New Caledonia and the Treasury Islands, recording many aspects of the soldiers’ lives in pencil and watercolour. We do not know if Kendall received any formal training, but the quality of his work suggests that he may have.

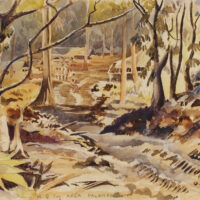

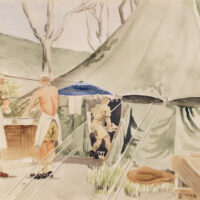

Archives New Zealand War Art has three water-colour paintings and two pencil drawings, the latter made in New Caledonia, from Kendall’s time in the Pacific (Figure 1 and 2).

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

One of the watercolour paintings appears to show the beach at Falamai on Mono Island where the initial invasion took place (Figure 3). The date, March 27 1944, four months after the invasion of Mono, confirms this.

Greg Moyle, Auckland based New Zealand war art collector, owns a substantial collection of Kendall’s work, which is based at the Auckland Museum and is the source for the other watercolour paintings shown below.

Kendall must have had a sense that he was creating an historical record with his paintings: he was methodical about documenting most of them with dates and locations. This is useful because it allows us to link them to specific events on the timeline of New Zealand’s presence in the Treasury Islands. Most of his paintings record scenes on Mono Island; there appear to have been none of Stirling Island, however, which suggests he must have been based on the main island of Mono.

The caption at the bottom of the watercolour painting shown in Figure 4 records that it shows “H.Q. Coy. Area, Falamai.” Bulldozer tracks indicate a location well back from the waterfront has been cleared from the jungle for the Company Head Quarters, providing for a substantial campsite. Coconut logs have been laid over the muddy ground to provide a roadway in the background.

Figure 5 appears to show the camp hospital, possibly the surgery facility, with doctors, one wearing a surgical mask, scrubbing up on the left of the composition, and a soldier on a stretcher being carried into the tent at the center of the frame.

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

Like Russell Clark, Kendall created a significant number of works which record everyday activities on Mono Island. Figure 7 records a group of soldiers chatting before retiring to their foxholes for the evening: the image was created about a week after the invasion when Japanese bombing was still a fairly regular occurrence. A rifle and separate bayonet are shown, the latter painted in silhouette, on the right side of the frame. Their spatial position within the painting is ambiguous and difficult to reconcile. The red cross in the background suggests that this might be located close to the Regimental Aid Post (RAP).

Figure 8 shows two soldiers engaged in writing home to New Zealand. The date of the watercolour, November 9, 1943, indicates that the work was made a little over a week after the invasion of the Treasury Islands. Kendall records the names of the two men along the bottom of the painting: Bert Ayson and John Sutton. Unfortunately, no information about either man comes up on the Auckland Museum Cenotaph website.

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

Figure 9 depicts a rudimentary thatched cottage and is titled in Pidgin English “House Long (Belong) Davis He Finish”. The date, 28 November 1943, is exactly one month after the invasion of Mono Island. Apparently somebody – an officer perhaps – has built himself something more substantial to live in than the standard army-issue tent.

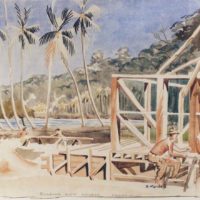

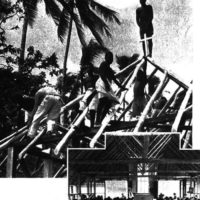

Kendall made a watercolour painting of the rebuilding of the local church at Falamai on Mono Island, which had been destroyed during the invasion of the Treasuries (Figure 10). The New Zealand soldiers took it upon themselves to rebuild the church for the islanders (Figure 11). The original church had been used as an ammunition dump by the Japanese and exploded when it was hit by a shell fired by an American warship during the invasion. The church built by the New Zealanders still stands in Falamai village.

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

Ironically, the photograph of the ruins of the church shows the British Union Jack flying next to it. Hoisted by the New Zealand forces soon after the invasion, the flag is evidence of the close relationship existing at the time between New Zealand and the “mother-country” (Figure 12). The British were not directly involved in the battle for the Treasury Islands.

Like so many of his contemporary artists in the Solomons, Kendall was fascinated by the technology of war, and especially the importance of the landing craft in their different permutations. Figure 13 shows two men watching a LCT (Landing Craft – Tank) unloading vehicles. The scene takes place on Purple 2 beach, Stirling Island, with Watson Island, situated between Mono and Stirling Islands, on the right, and Mono in the background. The date puts the tranquil scene at almost one month after the successful invasion.