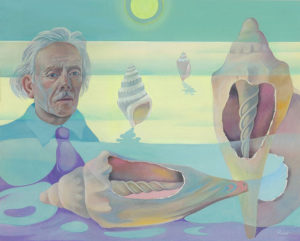

There are no photographs of William Reed on line. However, the 1951 watercolour “Memories of Shelly Beach” in the collections of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, is most likely a self portrait (Figure 1).

Yet Reed (1908 – 1996) was a highly respected artist amongst his artistic peers, friends and students. He was a highly skilled painter who spent his entire life, other than his time away at war in the Pacific, in Otago in the South Island. He attended the Canterbury College of Art in Christchurch and was a close associate of Rita Angus.

After his training at Canterbury College of Art, Reed worked for a time for company producing movie advertising material alongside Russell Clark. They became close friends and Reed was best man at Clark’s wedding.

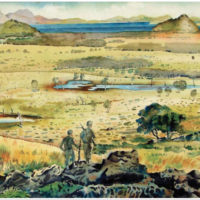

Reed’s early landscape paintings (Figure 2) were very similar stylistically to the Regionalist paintings of Rita Angus (Figure 3), whom he knew well, in the depiction of clear light and use of enhanced colour, hard-edged forms and mild abstraction.

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

During the war Reed belonged to the Field Ambulance Corps in the Pacific. He continued to draw and paint during his time in the army.

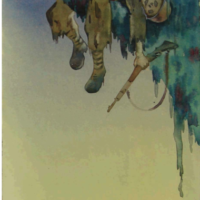

Reed’s war time work is particularly interesting because of the anti-war, humanistic themes that thread throughout his images, which is unusual in the war art of the time. Some are very explicit in their impressions of the human cost of combat. In Figure 4 the body of a soldier, discarded rifle at its side, decomposes into the soil on which it lays. In Figure 5 the body of a Japanese sniper hangs from a tree in the jungle.

His preoccupation with the death of soldiers is perhaps not surprising given Reed’s role in the Field Ambulance Corps. Bodies of dead soldiers are shown in his paintings anonymously and objectively as symbols of the randomness and futility of war. The fixed expression on the face of the camouflaged soldier in Figure 6 suggests, perhaps unintentionally, the dehumanising effects of war.

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

The painting may be compared with British photographer Don McCullin’s image of a shell-shocked US Marine staring into space during the war in Viet Nam (Figure 7).

Reed’s anti-war themes can be detected in some of the apocalyptic paintings Reed produced in the period leading up to the outbreak of WW2 in Europe: they represent a remarkable premonition of the horrors to come.

“Armageddon” painted in 1936 (Figure 8), features the heavily stylised figures of two women and two babies amongst the wreckage of bombed-out buildings. One mother and her baby wear gas masks. Christian symbolism (a cross, a Bible in the foreground) are juxtaposed with a stylised artillery shell flying toward the sun, a symbol perhaps of the Holy Conception. Picasso was painting “Guernica” at around the time Reed was working on this painting.

“Anno Domini” (Figure 9), painted in 1939, is a jumble of nightmarish imagery of premonitions for war and reminds us of some of the work of German post-WW1 artist George Grosz (Figure 10). Reed shows fat industrial-military-complex businessmen clutching bursting bags of gold coins, young men receiving army induction medical examinations, soldiers making bayonet charges, while Christ with his Crown of Thorns looks down on the scene and a putrefying soldier in a metal helmet stares out of the frame at us from empty eye sockets.

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

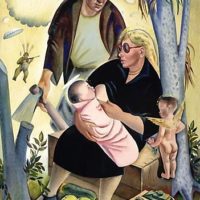

In one of Reed’s most symbolic and enigmatic paintings, “Adoration of the Madonna and Child”, undated but probably painted in the early 1940s (Figure 11), the Holy Family has been depicted as a New Zealand farmer with his wife and newborn child. He holds a grubber, a hand-tool used for clearing land for planting. She is wearing sunglasses in the glaring New Zealand light and suckles her infant, whose toy tank rests on the table in front of her. An angel looks on, in adoration of the new “messiah”, reminding us of the similar treatment of this theme by Renaissance artists like Leonardo da Vinci (Figure 12). The figures in Reed’s painting appear solid and well built, well fed and bordering on overweight.

The fruit and vegetables in the foreground of the painting serve as symbols of both the human fecundity implied by the birth of the “holy” infant and the earthly productivity of the farmer’s labours in this fertile “promised land”.

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

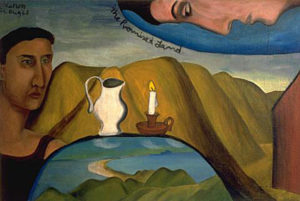

The idea of depicting the New Zealand landscape as the biblical “Promised Land”, characterised by the popular sobriquet “God’s Own Country” (often abbreviated to simply “Godzone”), occurs frequently in local art and literature. The concept is clearly epitomised by Colin McCahon’s visionary 1948 painting “The Promised Land” (Figure 13). The Promised Land is encapsulated in a bubble at the bottom of the frame, set within the dry hills of the South Island. An angel peers down from another bubble at the top, while the artist himself looks on from the left.

It is interesting to note that McCahon has also chosen to represent the observer of the idyllic scene, modelled on his own appearance, as a man of the land, a Kiwi sheep farmer, complete with black singlet. A simple shepherd’s hut is on the right side of the frame.

McCahon’s painting contains Christian iconography also: apart from the connotations of Christ as shepherd, the jug represents the Virgin as “Holy Receptacle”, the lamp alludes to Christ’s role as the “Light of the World”.

In Reed’s painting, paratroopers holding guns descend in the background. They are framed by a common New Zealand cabbage tree on one side and an olive tree, the universal symbol for peace, here symbolically cut back to a stump, on the other. The paratroopers suggest the incipient invasion of violent conflict into a peaceful and unsuspecting land, far away from the dark events happening on the other side of the world.

In this work Reed has created an unsettling vision of a Messiah for a new age, set in an idyllic New Zealand context and probably, like the other paintings included above, made in the early years of World War II.

Man’s Inhumanity to Man continued to be an underlying theme in Reed’s work while serving in the Pacific. While serving in the Field Hospital on Mono Island, Reed made records of the work of the Ambulance Corps operating on dying and wounded soldiers, producing several paintings of operations in progress, in fairly basic conditions, at the field hospital on Mono Island (Figures 14 and 15). Figure 16 depicts some of the wounded being evacuated on a landing craft.

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

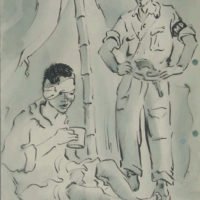

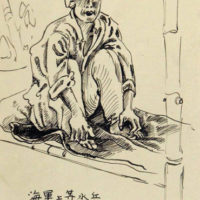

Reed made several sensitive portraits of the Japanese POW held at the hospital on Mono (Figures 17 to 19), possibly the man who was mentioned in Harry Stone’s diary. The captive has sustained a head wound and looks very young and nervous. He has written his name, Kouhei Mizuno, and that he was a First Sailor in the Navy, across the bottom of one of the works. Presumably he has been interrogated, and is aware that this is the only information he is obliged to give.

It would be interesting to know the circumstances of his capture and what became of him: Japanese sailors, like their counterparts in the army and air force, were instructed that it was dishonourable to be taken prisoner, and they were expected to die in battle. It was a common occurrence for shipwrecked sailors to swim in the opposite direction from rescue craft, rejecting help. It is likely that the young sailor was shipped back to New Zealand and was incarcerated in the Japanese POW camp at Featherston.

- Figure 17

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

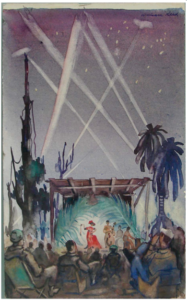

Reed made a painting of a concert, supposedly on Mono Island (Figure 20), but, as with his similar painting of “Movies, Mono” in the “Picture Theatres” section of this website, the location details in the painting do not literally support this: rather, the trees appear fantastical and otherworldly, not like the jungle vegetation of the Solomons, and the stage looks nothing like the St. James on Mono. The effect is of an event occurring in a fantasy world: almost as if the men have been transported to a parallel universe. Reed provides a Surrealistic twist even in his efforts to show a lighter side of the Pacific War experience.

It is interesting to compare Reed’s two versions of entertainment under the stars with Robert Laessig’s, also in the “Picture Theatres” section of the website, which treats the theme in a very similar way. In Reed’s work the men are transfixed by the action on the stage, while searchlights sweep the night sky for enemy planes in the background, a reminder of the ever present danger that is a part of their lives.

Like his friend Russell Clark, Reed was very aware of contemporary movements in the early twentieth century art and applied his knowledge to his own painting style. There are clear references to the Cubist movement and especially Surrealism. He must have found the latter movement particularly appropriate to the extreme sights he was witnessing. In several paintings he juxtaposes the grotesque elements of warfare with the beauty and delicacy of nature: a butterfly alights on a discarded rifle (Figure 21) , a pile of war detritus and army tents pollute a tropical landscape (Figure 22).

In another painting, reminiscent of the movie posters that Reed created before the war, searchlights cut across a dreamy, Disneyesque moonlit and starry sky in Guadalcanal as anti-aircraft shells explode the distance (Figure 23). One soldier, fox-hole to his left, apparently (improbably) shoots a pistol at the action above. There is a curious, probably unintended ambiguity about his right arm: is he firing a pistol into the sky or is he pointing at the action? It’s hard to tell. Another soldier stands holding a rifle, silhouetted in the background.

- Figure 21

- Figure 22

- Figure 23

In his efforts to explore alternative painting styles, Reed’s image of two mannequin-like soldiers manning an ack-ack gun (Figure 24) is reminiscent of some of Giorgio de Chirico’s early Surrealist works, e.g. “Le Muse Inquietanti (The Disquieting Muse)” 1916 (Figure 25). Like de Chirico’s painting, the figures’ heads have been represented as strangely elliptical, featureless, tear-drop shapes. Their bodies are draped in what appear to be bandages. The landscape is strange and dreamlike, the colours exaggeratedand unrealistic.

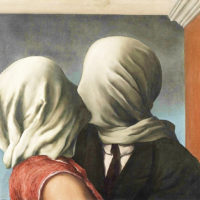

There are also similarities to some of Surrealist Rene Magritte’s work (Figure 26) in the nightmarish and dehumanising depiction of the individuals.

- Figure 25

- Figure 26

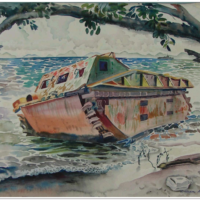

The impact of discarded war machinery is another recurrent aspect of Reed’s Surrealist take on the war in the Pacific. Abandoned tanks (Figure 27), boats (Figure 28), and Japanese artillery (Figure 29) litter the foreshore.

- Figure 27

- Figure 28

- Figure 29

A boot and helmet lay in the jungle (Figure 30), an apparent marker sticking out of the ground suggesting this could be a Japanese soldier’s grave site. The helmet appears pushed out of shape, making the nationality of its departed owner indeterminate. The frond laid in the foreground, perhaps placed by the retreating Japanese forces, symbolises peacefulness and eternal rest. The hastily placed wreath brings a sense of civility and caring to the scene.

Fighter planes fly over blasted coconut trees (Figure 31), huge four engine bombers threateningly overfly an unsullied tropical vista (Figure 32). Even the untouched sprawling landscape, probably in New Caledonia, appears strange and other-worldly (Figure 33).

- Figure 31

- Figure 32

- Figure 33

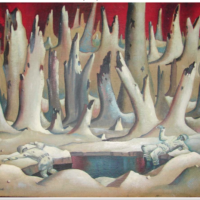

Reed’s painting “Beach Head, Mono Island” (Figure 34) looks more like a scene from the Western Front, and more specifically, Paul Nash’s “We Are Making a New World”, (Figure 35) a painting which also influenced Russell Clark. The shattered tree trunks appear as the restless ghosts of the men who died in the conflict. Two rotting bodies, possibly an Allied soldier on the left, a Japanese on the right, lay next to a stagnant pool in the foreground.

- Figure 34

- Figure 35

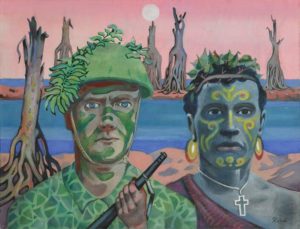

In one of Reed’s strangest paintings, created in 1946 after he returned from the Pacific, two stylised men appear standing in front of a bizarre, alien landscape of blasted banyan trees (Figure 36). There is an equivalence here which references the tribal nature of warfare. Both wear their versions of tribal face paint. The soldier on the left, a blue-eyed European whose face markings are a continuation of his camouflaged uniform, helmet festooned with vegetation and rifle in hand, is paired with, yet protectively stands in front of, a dark-eyed Melanesian wearing a Christian crucifix and huge native ear-rings, face decorated in arcane tribal motifs, black hair entwined with leaves. A pale sun rises or sets in the background.

The message seems clear, albeit culturally patronising: these are individuals from two contrasting cultures, each with their own set of body ornaments and cultural values: one the cold-eyed war maker, the other more spiritually evolved, peaceful, self aware.

They stand side by side, but the European with the rifle is protecting the colonised, Europeanised, Christianised Melanesian way of life from the Japanese enemy.

After the war, William Reed taught at Dunedin School of Art, and after the school combined with the Otago Polytech, was for a time the head of the new institution. His paintings are held in many public galleries throughout New Zealand, including the Auckland Art Gallery, Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa, and Dunedin Public Art Gallery, which owns a substantial number of his works from the war and before.

Reed was to spend the rest of his life in the southern part of New Zealand and continued to paint until his death in 1996.