War Trophies: A war trophy has been defined as any object captured during war which is evidence of victory or power and symbolizes the enemy’s defeat. The practice of taking war trophies (also known as “booty”, “spoils”, “plunder” or “pillage”), and war souvenirs, is as old as warfare itself, and has historically been practiced by the tribes and armies of nearly every culture on Earth.

War trophies and spoils are taken by nations for political and/or economic reasons, while war souvenirs are taken, made or bought by individual soldiers, generally for personal reasons.

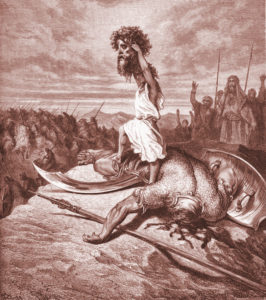

In the Biblical story of David and Goliath, David uses his opponent’s own sword to hack his head off after slaying him with his slingshot (Figure 1). David sends the head back to Jerusalem, but he takes the armour to his own tent. Thus, in addition to being a parable about the righteous weak defeating the powerful, the story of David and Goliath can be seen as a metaphor for the state’s versus the soldier’s rights of appropriation of property during wartime.

Goliath’s severed head is a war trophy. It is a powerful symbol for the decapitation of the Philistines’ leadership and the resulting emasculation of their war effort and will to fight. The leadership of the Philistines is metaphorically decapitated and rendered impotent, the Hittite army’s power that the head signifies being delivered – symbolically transferred – to King Saul in Jerusalem.

Goliath’s body armour represents the personal spoils/booty that David as victor has earned the right to keep by his actions in defeating the invaders. The armour becomes David’s personal property, which he can keep as a war souvenir or sell as war booty. The Bible does not record what he did with it.

In most eastern and western cultures in ancient times (i.e. roughly before the fall of the Roman Empire in 576 CE), anything the vanquished enemy possessed was forfeit to the victorious army. This included flags and standards, weapons and armour, horses and cattle, wagons, coaches and chariots, slaves, wives, and concubines, land, buildings, crops, homes and possessions. Also included were the opposing army’s warriors themselves, who might be kept or sold as slaves, or put to the sword and / or mutilated as the victorious leader decided. Sometimes prisoners were blinded by their captors, as punishment and humiliation, but also to prevent their escape.

As tokens of a victory, as well as to send a powerful psychological message to other potential enemies, the bodies of the defeated soldiers were commonly mutilated and body parts collected to be taken back to the victorious army’s homeland. Following the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE, Rameses’ troops cut a hand off each enemy corpse. These were taken back to Egypt so that a tally could be made of the number of Hittite soldiers killed in the fight (See “Egyptian War Art” section).

In the year 1300 BCE, the Egyptian king Menephta defeated a combined force of Libyans and Greeks. As proof of his triumph, Menephta brought back thirteen thousand penises his soldiers cut from opposition soldiers, thus emasculating them in the afterlife as well as providing a record of the number of enemy killed.

On a monument to Menephta at Karnak the tally of penises was itemised:

- Penises cut off Libyan generals: 6

- Penises cut off Libyans: 6359

- Penises cut off Sicilians: 222

- Penises cut off Etruscans: 542

- Penises cut off Greeks: 6111

Most ancient cultures believed that soldiers who had allowed themselves to be captured had lost all rights to be treated as human beings: they become chattels whose continued existence was at the discretion of the conqueror. (The harsh treatment and atrocities committed by the Japanese on captured Allied soldiers in World War II can be explained in part by this attitude, which was a carry-over from the bushido tradition of the Samurai.) Since the living bodies of the vanquished belonged to the conquering power, the victors “owned” them and could treat them as objects rather than as human beings. The prisoners were effectively dehumanised.

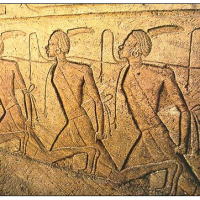

The Egyptians collected prisoners during their conquests and took them home as slaves. Slaves were looked on as valuable economic units and the capture and binding of defeated troops features frequently in Egyptian relief sculptures. At Rameses III’s Medinet Habu temple, depictions of prisoners taken at the battle with the Sea People are shown with their arms, in Rameses’ own words, “pinioned like birds” (Figure 2). Captured soldiers were often branded then conscripted into the Egyptian army.

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

Mutilation of the living and dead was common in these ancient cultures. The collection of heads was routinely practiced. Decapitation was not only the ultimate indignity that could be inflicted on the corpse of the slain soldier: a head separated from its body possessed powerful and shocking symbolism: the victim was totally dehumanised and the manner of his death sent a powerful message to the enemy that this would be the fate of any defeated soldiers.

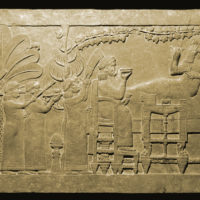

Heads were often displayed on stakes or hung in trees to strike fear into the opposing forces. In a relief sculpture Ashurnasirpal II, king of Assyria (modern day Iraq) from 833 to 859 BCE, is shown reclining in a garden in his palace (Figure 3). In the tree on the left of the relief hangs the severed head of Neumann, king of Elam (Figure 4). In this example the head is being displayed as an example and as a form of psychological threat: a warning to anybody foolish enough to challenge the leader of the consequences of their actions before they even start.

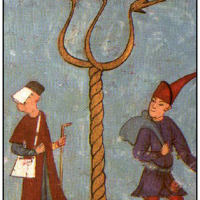

The “Serpent Column” (Figures 5-7), created in Delphi and located today in Istanbul, was made 2,500 years ago by the Greeks from the melted down body armour of the defeated Persian army. The armour of the enemy forces thus became part of the ritualistic memorial that the Greeks created to give thanks and make sacrifices to the gods for their victory. The very materiality of the defeated soldiers’ armour became an offering back to the gods who made the victory possible.

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

Ancient Romans also collected spoils of war during their conquests. These were carried back into the city of Rome with great celebration and pageantry in triumphal processions. Roman officers and soldiers were permitted to keep war booty to subsidise their military pay. The Roman cinerary urn from the collection of the New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (Figure 8) shows the spoils of war presumably captured by the individual whose ashes were one once contained within. Military spoils would be divided up among the men following a successful battle, a tradition which continued well into recent history. Ritualised humiliation of the enemy leaders was an important part of Roman warfare. Captured kings, queens and generals were paraded through the streets in chains, usually before being executed. Cleopatra committed suicide rather than face the humiliation she knew was in store for her if she were captured by Octavian, who later became the emperor Augustus.

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

The Arch of Titus (Figure 9) was built by the emperor Domitian to commemorate the victories of his brother Titus in 82 CE. The objects shown being carried into Rome on the Arch of Titus are from the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem following its destruction by Titus’s army in 70 CE. Prominent in the relief sculpture on the arch is the sacred Menorah, but we can also see the Table of the Shewbread (sacred bread) and the silver trumpets which called Jews to Rosh Hashanah (New Year in the Hebrew calendar). The placards carried by the soldiers would originally have had the names of conquered cities inscribed on them (Figure 10). There is very strong evidence that the Colosseum, begun by Vespasian and completed by his son Titus, was built from marble taken from the Temple.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colosseum

War Souvenirs: The boundary between war trophies and war souvenirs is often blurred. A war souvenir can be defined as a personal memento of a war or battle that an individual has been involved in or with, either directly (e.g. as a soldier) or indirectly (e.g. as a visitor to a war site). Souvenirs are generally solid, three dimensional objects. We don’t usually regard a painting or drawing as a souvenir. Although a souvenir can include a two dimensional, graphic component, souvenirs are mostly tactile, solid items that can be held in the hand or displayed on a shelf or mantelpiece.

An old soldiers’ saying is that being in the army is “5 per cent sheer terror, 5 per cent waiting, and 90 per cent pure, unmitigated boredom.” For servicemen, making souvenirs traditionally offered a way to fill in hours of boredom between battles or manoeuvres. Boredom is a problem experienced by all soldiers to some degree but especially by prisoners of war, so it is not surprising that many POW’s turn to making artworks to fill in the time.

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

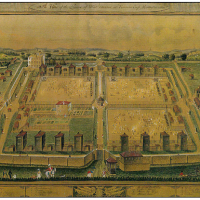

The English created the first POW camp. During the Napoleonic War they imprisoned captured French soldiers and sailors at Norman Cross Prison in Cambridgeshire, which held prisoners between 1797 and 1814 (Figure 10). Some of the French prisoners made beautifully and accurately detailed model ships (Figures 11 and 12) with bone planking, rivets made from wire, and human hair for rigging. Soup bones were acquired as raw material from the prison’s kitchens. Other materials used to make models and artworks included bedding-straw and wood. Pictures were made from different coloured human hair. Hair was also used to make bracelets and watch-chains. Straw was used to make hats and bonnets, tea caddies, trinket boxes. These were sold to the public from a stall just inside the prison entrance.

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

- Figure 15

Sailors have also traditionally endured long hours at sea with nothing to do, especially in long months at sea on sailing ships. Some made scrimshaw art to fill in idle hours: designs engraved on to whale bone, whale teeth and walrus tusks (Figures 13 and 14). These were often made in matching pairs of whale teeth or walrus tusks. There is a poignant progression from engraving pairs of whale teeth to scoring designs on pairs of nautilus shells (Figure 15), made not by sailors but by land based craftspeople, to be sold as travel souvenirs. Ironically, as in the examples shown here, such artefacts were often sold to visiting sailors. These examples have been in my family since the early twentieth century, when they were bought by my grandfather while in the navy in World War 1.

Many sailors in the age of sail would use the sewing skills they had acquired for sail and uniform repairs to make embroidered pictures, which would be sold on their return to port to supplement their sailors’ pay (Figure 16). Perhaps not surprisingly, embroidered artworks hold a special place in the iconography of many of the world’s navies.