As in World War 1, souvenir hunting was a major preoccupation, bordering on an obsession, among many of the Allied soldiers in the Pacific War. Like soldiers in most wars, Allied and American troops were constantly on the lookout for enemy items to collect. Although it was expressly forbidden to rob bodies of fallen enemy soldiers, the drive to plunder Japanese corpses for watches, wallets, belts, caps and ultimately even body parts was common, the justification of the soldiers for their actions conditioned by racist attitudes toward Japanese in general, and a loathing of Japanese soldiers in particular. Anything was considered fair game.

In his Guadalcanal diary Harry Stone reports seeing a ring finger cut off from the severed arm of a dead Japanese airman for the signet ring on it:

“The working party that was on this morning were lucky enough to have to go down past Henderson field with a load of petrol. They saw the remains of one of the planes that were shot down last night…There were seven in the crew, all in pieces, the biggest piece was the torso of one, but even he had his stomach tore open. They saw an arm that someone had cut the signet finger off to remove the ring. Barbarous, but the Jap had finished with it.” Harry Stone, Guadalcanal, Tuesday 21st September 1943.

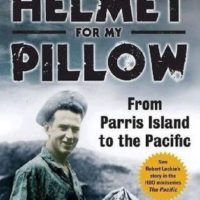

In his book “Helmet for My Pillow” Robert Leckie describes a fellow Marine on the island of Peleliu wearing a bag around his neck containing his collection of gold teeth which he had smashed out of the mouths of dead and dying Japanese soldiers.

Following the invasion of Mono Island, Harry Stone describes in Diary No. 2 the rush to collect souvenirs by New Zealand and American servicemen. He looked on enviously as a New Zealand officer strolled past with a Japanese “Kinuta” outboard motor, wondering how he was going to get it home.

“November 2nd 1943: I saw Lt. Pine go past one day carrying a Japanese out-board motor he had souvenired from somewhere. It was a Kinuta motor (Figure 1), about four horse-power, and very much like the Johnson I left at home with my father. I’m sure I would have put it to more use than him, providing I could have got it home.” Harry Stone, Mono Island, Tuesday 2 November 1943.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

“One bulldozer driver made history by attacking a machinegun nest with the bulldozer, he held the blade up high to protect himself and scooped up the Japs, guns and all. It made a hell of a mess of the Jap bodies, “Snow” Armstrong (G Troop) went through their pockets and got a few souvenirs.” Harry Stone, Mono Island, Saturday 6 November 1943.

This famous incident became the subject matter of a number of drawings and paintings which mythologised the actions of Aurelia Tassone, the Seabee at the controls of the bulldozer. The photograph in Figure 2 shows the aftermath of the destruction of the Japanese machine-gun nest.

Harry was not above collecting a few souvenirs himself:

“This morning “Dipper” and I boarded the barge that brought our water ration and went over to Mono Island…We got a few souvenirs – a clip of Japanese rifle rounds, two 30 mm. shell cases, two N.Z. bakelite hand-grenades (which I hope to get deloused tomorrow) and a photo from a Jap’s wallet! I think that is all. I have lost the buckle off my belt so when I saw a swell brown leather belt on the beach I picked it up – boy did it hum (smell)! When I looked around, I could see various pieces of Jap leather web gear…It had belonged to one of the Japs buried by the bulldozer on the first day so I knew where it had come from…” Harry Stone, Stirling Island, Monday 15 November 1943.

The War in the Pacific was vicious and visceral in ways that were even more horrific than the War in Europe. The conditions the war was fought in were extreme: many felt the war was as much against the heat, rain, poisonous insects and snakes, as well as tropical diseases and boredom, as it was against the Japanese. Medical problems included malaria, dengue fever, tropical sores and rashes, foot and crotch rot caused by the heat and humidity.

Uniforms and boots, even leather watchstraps, rotted in the constant humidity. There was also the chronic sense of isolation and homesickness to deal with, created by the vast distances and remoteness of the Pacific islands. In 2010 I interviewed a veteran who was still being treated for an infection on his leg that he contracted in the Solomon Islands.

“About ten days ago Colonel Blake (ex Middle East), came back from Vella Lavella with dysentery, he said “Ten days fighting in the Pacific is worse than ten months in the desert!” Hell, I’m fed up with this war, wish to hell I was back in dear old NZ.” Harry Stone, Guadalcanal, Sunday October 17 1943.

There were many cases of suicide among Allied servicemen, including two young American soldiers on Guadalcanal that my father records as shooting themselves and one New Zealand man whom he saw jump from his troopship as it came into Noumea Harbour and swim toward the horizon. The man disappeared into the open sea before a boat could be organised to bring him back.

But it was the fear of having to fight the Japanese that weighed most heavily on the minds of most men. The “Japs” or “Nips” were thought of, and were portrayed by officialdom as fanatical, sadistic, cunning jungle-fighters who ignored the accepted rules and decencies of warfare. A display plaque in the Pacific section of the “Scars on the Heart” permanent exhibition at Auckland War Memorial Museum states that while there was among Allied soldiers in Europe “a grudging respect for the Germans, there were no such feelings for the Japanese.” In 1942 General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific, commented that “Japan, not Germany, is the main enemy. Life under a civilized race (i.e. Germany) would be tolerable.”

Were Japanese war crimes worse than that of the Germans? While the Japanese did have POW camps and prison camps for alien civilians, both in mainland Japan and the areas they conquered, they did not construct concentration camps solely dedicated to the elimination of entire races or sub-groups as the Germans did, nor did they have explicit policies of mass genocide. While the severity of their war crimes toward Allied prisoners of war is undeniable and inexcusable, Japanese behaviour toward Allied prisoners was rooted in the ancient Samurai code of Bushido: “The way of warriors”.

https://china.usc.edu/sites/default/files/forums/Samurai%20and%20the%20Bushido%20Code.pdf

A twisted, corrupted interpretation of the Bushido code by the militaristic Japanese government lead to the brutalised, dehumanising treatment of raw Japanese soldiers by their superiors. This attitude became part of the expected conduct indoctrinated into the Imperial Japanese Army and was carried by rank and file soldiers into the battlefield.

There was strong evidence to support the notion of the bestial conduct of the Japanese forces in the Pacific. At the time of the American invasion of Guadalcanal, photographs which had been discovered in a Japanese bivouac circulated among the men showing the mutilation of Marines on Wake Island, which had been over-run by Japanese forces soon after Pearl Harbour. Japanese and American bodies on Guadalcanal had been booby-trapped. Japanese soldiers would sometimes pretend to be wounded, call for an American medic then shoot them or detonate a grenade when they came to help.

These incidents contributed to a remorseless, “kill or be killed” attitude toward the Japanese amongst the Allied soldiers. The Americans decided, in the words of US Marine veteran Donald Fall, “to get down to their level.” Stealing wallets and wedding rings gave way to defiling Japanese soldiers bodies and collecting body parts: ears, noses, teeth, skulls and bones as souvenirs.

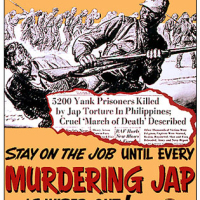

Official Allied propaganda, the media and popular culture during the war period portrayed the Japanese as a primitive, barbaric, uncivilised and un-evolved “other” as in the newspaper clipping found in one of Harry Stone’s diaries (Figure 3). We can only speculate as to why he took the trouble to cut this illustration out and save it, but it underscores the prevailing attitude that Japanese were seen, from the average New Zealand soldier’s point of view, as being like creatures from another planet.

Racial elements underpinned the War in the Pacific that were intrinsic to the fighting from the outset and which were largely the product of entrenched cultural attitudes and prejudices on both sides of the Pacific. American attitudes toward the Japanese were fostered by the urge to take revenge not only for Pearl Harbour, but for the atrocities committed against their soldiers in the Pacific Islands and in South East Asia (Figure 4).

When one country is at war with another, it is common for those in charge of the war effort on both sides to portray the enemy as uncultured and even sub-human. Depicting the enemy as uncivilised, bereft of culture and having less intelligence than vermin is intended to make the job of eliminating them less of a moral dilemma for the soldiers doing the killing. The enemy’s culture itself may be derided and art may be used to denigrate the status of the other side. In 1942, Australian General Thomas Blamey told his troops in Papua-New Guinea that beneath the “thin veneer of a few generations of civilisation”, the Japanese soldier was a “sub-human beast, who has brought warfare back to the primeval, who fights tooth and claw, who must be beaten by the jungle rule of tooth and claw”.

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

American propaganda depicted the Japanese as a race of sub-humans and vermin: possessing an unthinking automaton’s loyalty to their emperor. American drill instructors admonished new Marine recruits with the following: “Every Japanese has been told that it is his duty to die for the Emperor. It is your duty to see that he does so”.

US President Truman, in his efforts to justify his decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, actions the Japanese to this day consider war-crimes, commented: “The only language (the Japanese) understand is the one we have been using to bomb them. When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him as a beast. It is most regrettable but nevertheless true.”

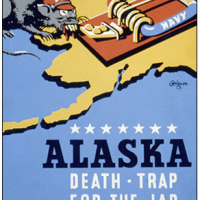

The stereotype of the Japanese as vermin is graphically depicted in a US government poster of 1942 (Figure 5). The Japanese attacked the Aleutian Islands off Alaska at the same time as the Battle of Midway (4 June 1942) in the Pacific as a diversion from the main battle. This poster was produced in response to the fear that the Japanese would also attack Alaska.

Today the poster is deeply offensive in its characterisation of the Japanese as rats. Clearly, at the time it was intended to reinforce the notion among Americans that the Japanese were an uncivilised subspecies on the level of vermin and deserving of merciless annihilation.

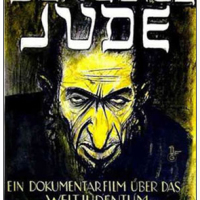

Interestingly, the Nazis had used similarly offensive images in their depiction of Jews in their 1940 propaganda film “The Eternal Jew” (Figure 6). In other propaganda aimed at dehumanising Poles and Russians, the Germans coined the term “untermenschen”, literally “under (sub) people”: a lower, animalistic form of human that was not entitled to the same basic rights as other, more highly evolved beings.

Ironically, in stigmatising the entire Japanese race and civilisation in the same way as the Nazis had done to the Jews, the Allies adopted the very racist tactics they condemned and were fighting against in the Axis powers. Unlike Germany, Japan had refused to sign the Third Geneva Convention in 1929 dealing with the humane treatment of Prisoners of War and they did not recognise the traditional rules of warfare. Soldiers were trained in the traditional Samurai warrior Bushido code to never surrender and that the ultimate humiliation for a soldier was to be captured alive. They had been indoctrinated to believe that it was infinitely better to die in battle.

“In those days we naturally accepted the tradition that Japanese Samurai, in olden times, fought with a sword. I believed that by carrying a sword ourselves, we became Samurai.” Japanese veteran, “Hell in the Pacific”, History Channel documentary.

As occurred during the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, decapitation with the samurai sword was used as a method of terrorising and controlling prisoners as well as striking fear into Allied soldiers. Word of Japanese beheading Allied prisoners soon spread around the soldiers fighting in the Pacific. (Japanese officers were required to wear a samurai sword, but those they were issued with were of relatively poor quality, being mass-produced from inferior metal, some of them being made from recycled rail-lines in the absence of high quality steel. After the war the Japanese government made them illegal and destroyed thousands of them.)

The effect of Japanese atrocities was to further reinforce American soldiers’ attitudes toward the Japanese as a race that had to be expunged from the planet by any means available. The Japanese refusal to sign the Geneva Conventions setting rules for treatment of prisoners of war resulted in abuses that many American soldiers felt they were justified in avenging through their own treatment of the Japanese. A sign erected on Tulagi Island in July 1943 exhorted American soldiers to kill as many Japanese as they possibly could in order to shorten the war:

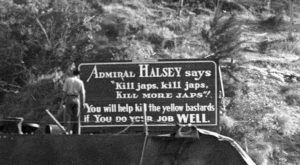

Admiral Halsey says “Kill Japs, kill Japs. KILL MORE JAPS! You will help kill the yellow bastards if You do your job WELL.” Admiral William “Bull” Halsey was Commander of South Pacific Forces. (Figure 7)

As reports spread of Allied soldiers and POW’s being beheaded by samurai sword-wielding Japanese officers gained currency, similar reciprocal atrocities began to be practiced by G.I.s. Ancient military traditions of mutilating bodies and collecting body parts and severed heads remerged. It was not uncommon to see Japanese heads displayed as trophies on stakes along beaches and in the jungles (Figure 8).

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

“You get into a nasty frame of mind in combat. You see what’s been done to you. You’d find a dead Marine that the Japs had booby-trapped. We found dead Japs that were booby-trapped. And they mutilated the dead. We began to get down to their level.” US Marine veteran Donald Fall

“At daybreak, a couple of our kids, bearded, dirty, skinny from hunger, slightly wounded by bayonets, clothes worn and torn, wack off three Jap heads and jam them on poles facing the ‘Jap side’ of the river … The colonel sees Jap heads on the poles and says, ‘Jesus men, what are you doing? You’re acting like animals.’ A dirty, stinking young kid says, ‘That’s right Colonel, we are animals. We live like animals, we eat and are treated like animals – what the fuck do you expect?'” Ore Marion, U.S. Marine

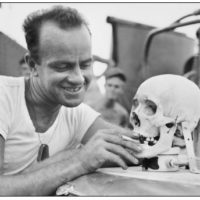

Responding to the Japanese practice of decapitation, a demand grew amongst the Marines and G.I.s for Japanese skulls as souvenirs. Skulls in good condition would reportedly sell for $35.00. Procedures were developed for cleaning and bleaching them, including burying them in ant-hills, towing them in nets behind ships and boiling them in large cauldrons (Figure 9). The processed skull would sometimes then be subjected to further indignities for the camera (Figure 10).

In a grotesque revisiting of World War 1 letter openers, President Roosevelt was sent a gift by a US Congressman of a letter knife made from the forearm bone of a Japanese soldier. When told what the knife had been carved from, he returned it, suggesting it should be properly buried. Despite the American authorities banning the practice of harvesting body parts, reminding troops that it broke international law, and pointing out that the Japanese would be morally and legally entitled to reciprocate, the practice continued to be prevalent.

A not uncommon practice by American troops involved smashing or tearing the gold teeth of Japanese dead (and often not quite dead) out with rifle butts or pliers. Some carried pouches around their necks to put them in. In his account of the aftermath of the invasion of New Britain, Robert Leckie mentions the presence of a man he identifies only as “Souvenirs”:

“The souvenir hunters were prowling among (the Japanese bodies), carefully ripping insignia off tunics, slipping rings off fingers or pistols off belts. There was Souvenirs himself, stepping gingerly from corpse to corpse, armed with his pliers and a dentist’s flashlight that he had had the forethought to purchase in Melbourne.” (Robert Leckie: “Helmet For My Pillow”, Figure 11)

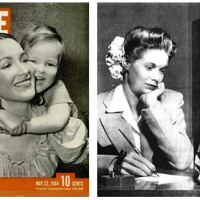

In May 1944, Life magazine featured a photograph, reminiscent of a seventeenth century memento mori painting, of Phoenix war worker Natalie Nickerson (Figure 12). She is seen writing a thank you note to her Navy boyfriend for sending her a Japanese soldier’s skull as a war souvenir. Her Navy lieutenant boyfriend had collected the skull while fighting in New Guinea. When her boyfriend left for the war, he had told her “I’m gonna get you a Jap!” Little did she think that he meant it literally. He and thirteen friends had autographed the skull and inscribed it “This is a good Jap – a dead one, picked up on the New Guinea Beach.” Natalie named the skull “Tojo” after Japanese Prime Minister. The officer who sent the skull was later traced and reprimanded.

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

This incident, reported in a folksy fashion in a leading American magazine, was widely publicised in Japan as an example of the barbaric behaviour that could be expected by any Japanese captured by American or Allied forces. Reports of American atrocities like this one reinforced the Japanese attitude amongst soldiers and civilians alike that it was better to die than surrender. Japanese media and propaganda coverage of the incident and other accounts of American atrocities were indirectly responsible for civilians, including women and children, throwing themselves from cliffs on Saipan Island rather than be captured by the Americans (Figure 13). They had believed Japanese propaganda that if taken alive by American soldiers, men would be shot, women would be raped, and children sold into slavery. (American loudspeaker pronouncements that they would not be harmed had little effect: one American soldier was later quoted as saying that having done all they could to prevent the suicides, they stood by and watched as the Japanese hurled themselves to their deaths.)

Such episodes also assisted the Japanese government reinforce a “death before surrender” mindset among the Japanese home islands population if the Allies were to invade. This suicidal mindset, witnessed by the Americans in Okinawa and Saipan, in turn helped persuade the Americans that an invasion of Japan would result in the death of millions of Allied forces and Japanese soldiers and civilians and that the use of the atomic bomb was the only way to end the war without millions of Allied casualties.

The American attitude toward the Japanese during the war is epitomised by the following dialogue from the film “Guadalcanal Diary”, (Figure 14) released at the height of the War in the Pacific. Based on the invasion experiences of Richard Tregaskis, “Guadalcanal Diary”, was first published by Random House in 1943 and was made into a movie in the same year. The American invasion of Guadalcanal had taken place in August 1942.

Private Anderson: “How do you feel about killing…people?”

Sergeant Malone: “Well, it’s kill or be killed ain’t it? Besides, those ain’t people…”

Private Anderson: “Yeah I know but the first time you got one?”

Sergeant Malone: “It was kinda rugged I guess. Then it’s just a matter of repetition. Quit thinking about it. You’ll go crazy…”