The term originally used to describe memorabilia from foreign countries was “keepsakes”. Such objects were also described as “curiosities” before the French term “souvenirs” became common.

Soldiers of both the German and Allied sides in World War I took souvenirs as tokens of the places they had been to and the battles they had fought. The urge to acquire souvenirs was especially common among soldiers from far off countries such as America and the British Colonies.

In the days of restricted travel the war was (initially at least) perceived as a great adventure and an opportunity to see something of the world by many young men, but especially those in the far-flung British colonies of Australia and New Zealand.

American troops had the reputation for being the most avid of souvenir hunters. The young Captain Harry Truman, later to be President Truman from 1945 to 1953, wrote to his fiancee back home after witnessing a downed and wounded German aviator being robbed of his boots by an American officer: “I heard a Frenchman remark that Germany was fighting for territory, England for the sea, France for patriotism, and Americans for souvenirs.”

After basic training at military camps such as Trentham, north of Wellington, young Kiwis were marched off to the battlefields in Europe (Figures 1 and 2). Most of these soldiers, having traveled from the other side of the globe, wanted to take home some kind of keepsake, some tangible evidence by which to remember their experiences.

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

The types of souvenir collected roughly fell into three groups:

1. Relics and objects found on the battlefield

2. Objects made from appropriated used war materiel by soldiers

3. Objects made by local “cottage industries” for sale to soldiers returning home: these might be made from used war materiel or local materials.

The latter two categories gave rise to the term “Trench Art”.

In the relentless search for souvenirs in World War 1, it was not uncommon for the enemy dead to be plundered, and even for corpses to be dug up by soldiers looking for belt buckles, buttons, helmets, wallets, watches, wallets and other objects. The prevailing attitude amongst the looters was that since the dead person had no further use for something, why let it go to waste? The corollary to this thinking was “If I don’t take it, somebody else will.” Both sides collected relics from the battlefield, and both sides contributed to a burgeoning souvenir market.

During Christmas Day 1914 soldiers from opposing sides to climbed out of their trenches and fraternised in “no man’s land” for the day, singing carols together, playing football, and exchanging souvenirs. (The British military authorities frowned on this behaviour and instructed their commanding officers in the field that soldiers must open fire on any Germans presenting themselves with or without weapons in any unofficial “truce” incidents in the future. There were rumours that some British soldiers had been forced back into their trenches at pistol point by some officers.)

While individual soldiers have made and collected war souvenirs throughout history, World War One is regarded as the Golden Age of the war souvenir and Trench Art. Two important factors contributed to this:

Firstly, there was the shear number of combatants involved in the war and the incredible amount of equipment and ordnance they carried and lost on the battlefield when they were killed. Objects dropped, discarded or on the bodies of the enemy were collected and concealed in kitbags to be smuggled home at the end of the war. The material available for souvenir hunters included items of uniform such as caps, gloves, epaulets, badges, buttons, belts and belt buckles, as well as rings, watches and military hardware including pistols, bayonets, helmets, gas masks, swords and field glasses.

Soldiers would collect objects and carry them in their backpacks until the weight got too much and they began discarding them to lighten the load. (Inevitably, somebody would often pick up the booty again somewhere else further down the column.) Many soldiers would hide their spoils in an abandoned building or bury them to be collected on the way home, only to be killed in battle, or because the landscape had changed to such a degree while they were away, they were not be able to find them. Misplaced caches of booty still turn up under farmers’ ploughs or demolition men’s hammers in France and Belgium even today.

The entry of America into the war in 1917 took the souvenir craze to a whole new level. One American veteran commented: “Man, if only we’d had a horse, or a wagon, or a truck, or a fleet of trucks. Would we have brought souvenirs home!” Souvenir collecting was transformed from a pastime to an obsession and then into a profitable business.

Unfortunately for most Commonwealth and American soldiers, before embarking at the wharf for the return home, it was common practice for officers to order that all kits be turned out for inspection. Soldiers were meant to have only what they had been issued with in their possession. All non-issue items were confiscated under threat of court martial – by officers who it was rumoured sometimes helped themselves to the choicest pieces.

Secondly, there was what Jane Kimball in her book “Trench Art: An Illustrated History” describes as “the staggering amount of artillery ordnance expended” on the front lines to “soften up” the enemy positions before a ground attack (Figure 3).

During the bombardment that preceded the Battle of the Somme alone, four million shells pounded the German lines. This would have produced a mountain of spent artillery casings, most of which would be sent back to the armaments factory for reloading. Inevitably, a percentage of shell casings were scavenged by soldiers and the public to be reconfigured as artifacts.

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

There was also a demand for chunks of exploded ordnance. After battles or bombardments, village women and children would rush into the streets and fields picking up shrapnel and shell fragments to sell as souvenirs to soldiers returning home. If it could be proved that a piece of shrapnel had been part of a barrage that had caused significant damage or death, the collector could demand a higher price. It was not uncommon for fights to break out over such fragments.

Many locals soon realised that a value-added component would make a souvenir more attractive to a soldier-buyer, particularly if it contained detail or references to local places and battles. As a result scores of cottage industries developed next to battle-fields in France and Belgium to supply soldiers with souvenirs and memorabilia to take home, often with place names, battle dates, flags and patriotic sentiments engraved on them.

The term “trench art” or “soldier art” has therefore come to denote a genre of souvenir created by soldiers and non-soldiers alike: hand crafted objects made from war material, produced in response to the demand for something more meaningful than simply a found or appropriated object. The makers of trench art were very aware that their product would be rendered more marketable to the burgeoning battlefield tourist industry through being made from the detritus of the war itself.

In a manner similar to the Greek’s use of Persian armour to make the Serpent Column at Delphi, the provenance of the materials used by the makers conferred a kind of sacredness by association upon the object.

In the years following the Great War, a significant tourist industry arose, as relatives of soldiers who had been killed on the Western Front traveled from around the world to make a pilgrimage to the site of the battle that had claimed a husband, friend or relative, or, for those who knew where their loved one lay, to visit an actual gravesite (Figure 4). Many people made the journey out of a simple curiosity to see the aftermath of the war, and the battlefield tourist trade is well patronised in France and Belgium to this day.

Clearly then, the term “war souvenir” can include not only objects made by cottage industries set up near battlefields to supply foreign troops with mementos to take home with them when the war ended, but also those produced after the war for tourists who came in increasing numbers to see the battlefields.

With the production of much war art taken out of the hands of the actual combatants, the provenance of the (generally unsigned) “trench art” produced at the time of World War I is often difficult to establish accurately. Much, if not most, was produced by the soldiers themselves during the war, but a large amount was made by small village industries during the war and in the years that followed.

Another factor contributing to the ambiguity surrounding the term “trench art” is the fact that only a small percentage of that made by the combatants was actually created in the trenches. Much of it was made behind the front lines by troops on furlough or recuperating from wounds or gas attacks in hospital (Figure 5). Wounded and psychologically scarred servicemen were encouraged to participate in art and craft classes as a form of mental and physical therapy. The therapeutic value of “working with the hands” was recognised by those in charge the rehabilitation.

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

From a purist’s perspective perhaps the only type of art that qualifies as trench art is that which can be shown to have been made in, or even of, the trenches themselves.

A photograph taken on the Western Front shows a French soldier modelling a female figure into the clay wall of his trench (Figure 6). A photograph from the Gallipoli Campaign shows a Maori hei-tiki design carved into a wall (Figure 7: refer also to “Migration of War Art Imagery” section of this website).

There are also reports of soldiers pressing badges and buttons into the bottom of a trench and making casts of them using lead made from melted down bullets.

It appears that New Zealand soldiers liked to leave their mark on the land wherever they went. In France the “New Zealand Tunnelling Company” were charged with excavating underground tunnels to link up chalk caves under the countryside around Arras in order for British troops to launch a surprise attack on German lines. A wall carving, still visible today, in one of the caves includes two fern leafs and the word kiaora, Maori vernacular for “Hello” (Figure 8).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Zealand_Tunnelling_Company

Perhaps the ultimate example of “land art” created by New Zealand soldiers was the “Bulford Kiwi”, made by members of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF), not while on the Western Front but while awaiting repatriation home after the war (Figure 9). The men were keen to return to New Zealand as soon as possible, but there was a shortage of troop ships to take them. Following several riots by the impatient soldiers, and perhaps inspired by the famous Uffington white horse carved into a hillside in Oxfordshire around 1000 BCE (Figure 10), their commanding officer decided in early 1919 to keep them busy by setting them the goal of carving a gigantic kiwi into the chalk hill behind their camp near Stonehenge in Wiltshire. The kiwi was designed by Sergeant-Major Percy Cecil Blenkarne, a drawing instructor in the Education Staff, and carried out by the Canterbury and Otago Engineers Battalions.

The scale of the chalk kiwi can be gauged from the fact that the beak is some 46 meters long. The entire design covers 1.5 acres. The kiwi was covered with turf during WW2 so that German pilots could not use it for navigation purposes. It was uncovered and re-chalked by Boy Scouts after the war. In spite of their well-meaning motivation, the kiwi appears to have lost some of its originally graceful lines in the process (Figure 11). An interesting footnote: in the years following the war the kiwi was maintained by the Kiwi Shoe Polish company from their offices in London, who paid a group locals to keep it clean and clear of weeds.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulford_Kiwi

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

Most soldier art was of course created by individuals, rather than, as in the case of the Bulford Kiwi, entire companies of men. By far the most popular object to use as the basis for singular souvenir-making on the front lines was the artillery shell casing: the brass cylinder that was the base of the artillery shell and contained the gunpowder charge. It could be used in its original form or cut up and beaten out to produce pieces of flat metal.

Shell casings provided the perfect material and basic cylindrical shape for the production of vases and umbrella stands, dinner-gongs, cups, chalices and other ornaments in an endless variety of ornately decorated designs which reflected the popular Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau styles of the time. Perhaps inspired by the examples of sailors’ scrimshaw using pairs of walrus tusks or whale teeth, works made from shell casings were often made in pairs and sets, sometimes commemorating associated battles or places, such as Argonne/Verdun, Ypres/Somme, Yser/Ypres. (Figure 12).

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

The cylindrical form of the shell casing is sometimes echoed by the use of bone as a carving medium. Bone had long been a popular carving medium for soldier artists and was commonly used by French POW’s at Norman Cross prison. An ox’s shin bone from the camp kitchens would be cleaned and bleached, then carved to create vases, pencil holders, napkin rings and candlestick holders. Bone was also a popular choice of medium in the Great War (Figure 13).

The medium of bone carving was taken to an obscene degree in WW2 when an American G.I. carved a letter knife from a bone of a dead Japanese soldier’s forearm (refer to “Souvenir Horrors” section of this website).

The letter-opener or letter-knife was a common form of trench art on both sides of the trenches in WW1. Like the vases and umbrella stands made from artillery shell casings, they remained a popular art form in WW2. As with the shell casing itself, the letter knife provided a basic shape that lent itself to almost limitless invention. In an era of prolific letter writing, this was a functional item which would often be personalised with the artist’s or recipient’s name. Letter-knife designs were often elaborate and some were made to look like bayonets, scimitars or daggers (Figure 14: refer also to “Anonymous and Semi-Anonymous Works in 3D” in this website).

- Figure 15

- Figure 16

- Figure 17

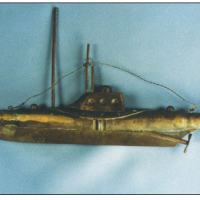

The new twentieth century hardware of war was the inspiration for models of aircraft, tanks and even submarines (Figures 15 – 17) made from “deloused” bullets drained of gun powder and flattened brass cut from artillery shell cases. Joining two rifle bullets end to end has created the distinctive shape of a submarine’s hull in the example shown here. Aircraft were also popular subjects, and from the earliest examples, deloused bullets were used to represent the fuselage. Most of these three-dimensional forms would be adapted by model makers in World War II, although the basic designs changed to reflect more the modern equipment. The popular use of the twin fuselage design of the Lightning P-38 fighter plane for model making is a good example of this.

Embroidery was a popular medium with the public at the beginning of the twentieth century and as the travel age took hold more and more (generally wealthy) people embarked on the Grand Tour of the world. It became possible to buy commercially manufactured embroidered silk postcards as souvenirs during one’s travels to exotic places. When the Great War broke out, many European soldiers’ wives made ends meet while their husbands were away by making embroidered postcards by hand to sell to foreign troops who wished to send messages home to assure friends and family that they were still alive (Figure 18). Patriotic themes featuring crossed Allies flags and sentimental dedications to family at home were popular topics. Embroidered post cards continued to be popular into World War II (Figure 19).

- Figure 18

- Figure 19

- Figure 20

Traditionally a sailor’s medium, embroidery also became a popular art form with many soldiers in World War 1. In addition to the necessary skills with a needle, sailors had access to sewing equipment and training to repair sails and tarpaulins in the days of sail. Soldiers were issued with needle and threat to repair tears to uniforms and replace buttons. These would sometimes be used to create embroidered imagery, often associated with a particular military unit.

In the example shown here, embroidery has been used to make a representation of a British regimental crest (Figure 20).