The picture shows an unidentified New Zealand soldier-artist set up and working on a landscape painting in New Caledonia circa 1943 (Figure 1). The image is a screen-capture from film shot by Gilbert Bryce Tomkinson.

War art is difficult to define because of its endless variety of form and creator, as well as the vast range of circumstances under which it is produced. In its broadest definition, and setting aside its political dimension (propaganda), war art is any form of art that is created by individuals or groups, with varying degrees of involvement in organised human conflict. Perhaps uniquely in the visual arts, much war art combines artistic and documentary functions.

Before considering a more refined definition of war art, we need to have an understanding of the main forms that war art takes

(a) Official war art: usually at the level of “fine art”, is produced by trained artists recording battles and other militarily significant events, as well as portraits of important people such as officers and war heroes, for the official record. Generally the job of the official war artist is to depict the military organization to which he belongs in a positive light: engaged in battles in which it is demonstrably winning or has been victorious. Official artists are not usually expected to depict military defeats or servicemen suffering casualties.

The line between art and propaganda can be a fine one, in the creation and production of this type of art. The “official” war artist is appointed to his position and receives a commission. He enjoys special privileges including time off normal duties to produce his artworks. In other respects however he is still a soldier. Fighting the enemy always takes precedence over making paintings. When the enemy attacks, he must lay down his brush and pick up his rifle. For this reason, few paintings, or drawings for that matter, are made during the thick of the fighting. A photographer or cinematographer is more likely to be required to record a battle or fire-fight because a camera can be quickly set aside when the rifle or machinegun is needed. For these reasons many official war artists base their “action” paintings on a photographic record. Many of Russell Clark’s paintings are based on photographs (for example, see his painting “Landing Ship Under Fire” in the section on “Migration of War Art Imagery”).

You might well ask therefore, what a painter brings to the image that the photographer does not or cannot? There is a strong belief, particularly amongst military bureaucracy, that the painter, through his use of composition, expressive colour and brushwork, can better create an impression of the actuality of battle than the coldly dispassionate camera is capable of (and that this was even more so before the advent of photography). Also, a painter can incorporate more of the detail of an action within a single image, thus creating a “truer” representation than a camera, which (in pre-digital times at least) was limited to a single viewpoint and capturing a single instant in a multitude of associated events. Thus, a painted representation can produce a form of “hyper-reality” that surpasses the documentary ability of the camera lens, no matter how good the photographer, by conjoining related episodes in the one depiction.

However there is a dangerously fine line between this form of documentation and romance or even propaganda. The camera records things and events as they really are (at least, it did before the invention of Photoshop). For this reason, paintings of slain troops are unlikely to carry the same force (and create as strong an emotional response) as photographs of the same subject.

(b) Unofficial war art: Obviously, the creation of war “fine art” is not just the preserve of the official war artist. Many trained and practiced artists go to war, voluntarily and involuntarily, and although conditions often make carrying a set of brushes and paints (let alone restocking them as they wear out or dry up) very difficult, they feel compelled to keep making art in the face of war. They seek to respond to and record their changing environment and circumstances, or simply want to “keep their hand in” until their return to civilian life (which sometimes included professional art teaching). It can be argued that the work of such artists, unencumbered by any official pressure to create images which are ideologically acceptable to the military hierarchy, has a greater level of autonomy and integrity, not to mention creativity and experimentation, than that of their official counterparts.

There were many New Zealand servicemen in the Pacific making artworks who were not official war artists yet were formally trained. Some were skilled, exhibiting artists before they went to war, others became established artists on their return. Others were art teachers before being called up and returned to their profession when their wartime service ended. Duncan McPhee’s drawing (Figure 2) depicts an artist recording the scene before him from a fox hole on Bougainville Island.

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

(c) Untrained artists. Such artists might take up a pencil or brush, or make simple artifacts or models, to find pleasure in the simple act of creativity (when their professional soldier duties generally involve much of the very opposite), to fill in empty hours, to record their experiences and surroundings in the absence (or prohibition) of a personal camera, to make something as a souvenir or memento to take home, or as something to sell or barter to supplement their military pay.

With this type of art making we are referring to “soldier art” or “trench art”, a form of amateur military art. Many writers have attempted to define these two interchangeable terms. Neither term is particularly accurate however, because not all war art is made by soldiers (some is made by sailors and pilots, some by officers and mechanics) and not all trench art is made in trenches (even in the First World War, much of it was made behind the front lines by soldiers who were on furlough or recuperating from wounds, some was made by cottage-industries in villages near the battle-fields to sell to the combatants or the increasing numbers of battlefield tourists).

Jane A. Kimball, in her sumptuous book “Trench Art: An Illustrated History” (Figure 3), reveals that the term “trench art” was invented by the French press, who published illustrations of objects made by “artisanant de tranchees” or “craftsmen of the trenches”. This was translated into “trench art” to describe art and craft made out of spent war ordinance and military equipment by actual soldiers or by civilians caught up in the fighting.

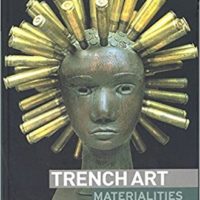

Nicholas J. Saunders attempts a definition of trench art in his book “Trench Art: Materialities and Memories of War” (Figure 4). His rather convoluted result points up the difficulty of formulating a definition to cover all bases.

According to Saunders, trench art is “any item made by soldiers, prisoners of war and civilians, from war materiel directly, or any other material, as long as it and they are associated temporally and/or spatially with armed conflict or its consequences.”

The “golden age” of trench art was undoubtedly the First World War (1914-1918) and some writers insist that the term can only be correctly applied to this period. The variety and inventiveness, not to mention the sheer quantity of art-objects made on the Western Front (mainly giant spent shell cases converted into vases, umbrella stands, dinner-gongs and the like) is truly remarkable.

The aesthetic impact of these art-objects gives the term “beating swords into ploughshares” new meaning. Objects whose functional utility was to deal out death on an industrial scale have been transformed into objects of often breathtaking beauty.

One of the reasons that trench art was so – well – entrenched along the front lines in the “War to End all Wars” was that there was so much raw material available to work with. The Battle of the Somme produced approximately four million heavy artillery shell casings on the Allied side alone after the initial bombardment that was intended to “soften up” the Germans before the main attack. (Never before in the field of human conflict had so much ordnance been unleashed in such a concentrated zone by so many guns, but ultimately to so little effect. The expenditure of 623,907 Allied lives resulted in an advance of eleven kilometers: the British themselves lost 420,000 men and gained three kilometers. This equates to two lives per centimeter of advance.)

Most of these empty casings were sent back to the armament factories in Britain to be refilled with projectiles and gun powder, but a substantial number made their way into the hands of soldiers and citizens to be converted into vases and umbrella stands (Figure 5).