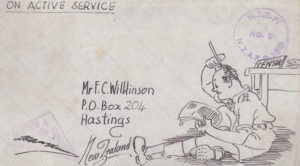

There are essentially two forms of censorship: firstly, that aimed at controlling the dissemination, inadvertently or deliberately, of information damaging to the enemy, through official monitoring of the press and private communications (Figures 1 and 2), and secondly, that aimed at controlling and vetting images – art, photography, film and video – that could aid the enemy on the one hand and affect the morale of citizens on the other.

In terms of visual communications, the line between art and propaganda has historically been a fine one. The value of war art as propaganda is often acknowledged by the authorities in charge of organising a war effort: thus censorship is closely linked to propaganda. It is not seen to be in the interests of the armed forces themselves, nor the general public, to show the graphic reality of war and fighting in any media. Emperor Trajan realised this when he constructed his column in Rome in 100 A.D. He ordered his sculptors to depict the Roman soldiers in a positive light and to refrain from showing the bloody realities of men fighting one another with swords and spears (refer to section on Trajan’s Column in “Roman War Art”.)

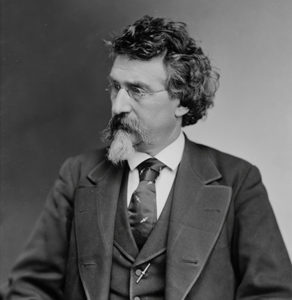

In the American Civil War, Mathew Brady’s photographs (most taken by his helper photographers Timothy O’Sullivan and Alexander Gardner) of graphic scenes of the carnage were rejected by the Union government because they were considered to be bad for public morale. Brady (Figure 3) had expected the government to purchase the photographs so that he could recoup the enormous amounts of money he had invested in creating them (100,000 glass plates at $1 a plate): when they refused, he was driven into bankruptcy.

Brady organised an exhibition of images, some in 3D, of Gardner’s photographs of the Battle of Antietam (17 September 1862) a month after the battle, in which an estimated 3,650 soldiers had died. For the first time, the American public were able to see lifelike images of the reality of war rather than images seen through the often idealising eyes of a painter (Figure 4).

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

Many people were shocked at the explicit depictions of young soldiers laying where they had fallen, the faces of individuals clearly recognisable, bodies contorted and bloated, on the battlefields. A New York Times report on the exhibition of Gardner’s images at Brady’s gallery stated: “If (Brady) has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along streets, he has done something very like it.” (Figure 5)

During the Vietnam War television crews and photo-journalists were given carte-blanche to go anywhere and film or photograph just about anything: in fact they were routinely flown around the country in army helicopters and transport aircraft. The broadcasting of the war into family homes on the nightly TV news (Figure 6) is considered to be an important factor influencing negative public opinion, which ultimately lead to America’s withdrawal .

The American military chiefs learnt the lesson of Vietnam in subsequent conflicts however. By the time of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the movements of videographers and photographers were strictly controlled by the authorities.

In the era of the internet, cellphones and hand held, camera-equipped aerial drones, one can only wonder how war images and footage could possibly be the controlled by the authorities on any modern battlefield. A photograph or video could be taken on a cellphone by an American soldier in a firefight in Syria or Afghanistan and seconds later be on his/her family computer back in the States: or in the newsroom of the New York Times, CNN or Fox Television, who would very likely each make entirely different use of the image or footage.

Censorship, or controlling the truth, may be enforced by governments or self imposed by the artist or writer. Self censorship is frequently practiced by war artists. Peter McIntyre, the official New Zealand war artist in the European War, described a wounded man who had both legs blown off and took half an hour to die. He decided that “knowing that there were people at home whose sons were killed and so on” it was inappropriate for him to record the agonized death of the soldier, adding “Who wants to see that?” McIntyre made a conscious decision about what he considered it appropriate to record.

It could be argued that it is not in the interests of the armed services to show the graphic reality of war and fighting, on the basis that if people were shown the true horror of war they may not be willing to participate in it. This has lead to criticism that all official war art is propaganda art.

Problems concerning provenance in war art are compounded by official censorship. In all wars, servicemen of every rank are made very aware of the necessity for secrecy and the consequences of divulging information to the enemy, which could potentially undermine operations and endanger fellow servicemen, were severe.

In his war diary, my father recounts how he wrote a letter containing material “of an intimate nature” to my mother and had to swear to the company padre that it did not contain any information that would be valuable to the enemy in order to avoid it being read by the censors before it was sent. At the end of his first diary, he wrote:

“FRIDAY 9TH. JULY 1943: Well I guess this is the end of the old book, 266 pages in 6 months, I should have a hell of a lot by the end of this war! My next problem is to get this book Home, as it sure won’t pass any censor.” (Harry Stone, Diary No. 1, New Caledonia )

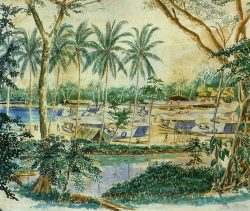

According to RNZAF Official War Artist Maurice Conly in his autobiography “Bring on the Artist”, he was instructed by the authorities while in the Pacific War to include representations of non-existent rows of trees (or delete existing ones) to disguise the location of some of his paintings of New Zealand Air Force facilities, so that the they could not be identified from the air, as in this watercolour painting by Conly of the New Zealand seaplane base at Halavo Bay on Florida Island in the Solomons (Figure 7).

Photographs and books of reproduced drawings published during and right up until the end of the war often contained a rider explaining that the locations had been deliberately left out. ‘Glimpses of the Pacific’, a booklet of drawings by ‘Two Kiwis’, Howard M. Purser and Dennis L. Chambers (Figure 8), two New Zealand soldiers serving in the South Pacific, states “Place names in most cases have been omitted” on the frontispiece (Figure 9). The very name of the book hints at a restricted view of the actions in the Pacific during the war . The images in the book appear quite innocuous today, but at the time they would have had to be cleared by wartime censors before publication (Figure 10).

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

Like the line between art and propaganda, the line between censorship and propaganda is a fine one. It has become a truism that in times of war, the first casualty is the truth. The comment was first made by Hiram Johnson (1866-1945), a Progressive Republican senator in California (Figure 11). His actual quote, “The first casualty, when war comes, is truth”, was said during World War 1.

Ironically, Johnson died on Aug. 6, 1945, the day the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima.