Establishing the historical record and origins of a piece of soldier art made in any conflict can be very difficult. In the Pacific the problems of tracking the provenance of an artwork can be made even more challenging by the widely dispersed nature of the fighting on islands separated by thousands of kilometers of ocean. The generally dismissive attitude of the New Zealand public, during and after the war, toward the contribution being made by the Kiwi forces in the War in the Pacific served to devalue the importance of the work in many people’s minds. The impression among many at home was that the New Zealand troops were having an easy war in the sunny islands of the Pacific with lots of relaxed swimming, exploring and socialising with the locals, while the “real war” was being conducted in Europe and North Africa. According to Reginald Newell in his Massey University thesis “The Forgotten Warriors”, the perjorative term used for the Pacific forces at the time was “coconut bombers”.

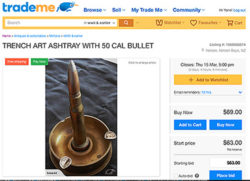

Problems of provenance apply especially to three-dimensional works. Works on paper such as drawings and watercolour paintings are more likely to be signed and often include specific information about the maker’s identity and circumstances, frequently written on the back of the work. In common with the trench-art produced in the Great War, most 3D art-works took the form of objects that could be displayed on a mantel-piece, side-board or display cabinet when the soldier returned home: model aircraft made from “deloused” bullets, vases, ash-trays (Figure 1), dinner-gongs (Figure 2) made from larger caliber shell cases and even cigarette lighters from rifle rounds (Figure 3).

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

More often than not these objects were not signed, nor were their creators recorded. Partly this was because the personal nature of the creations as mementos contributed to an attitude that it was or would not ever be of great interest or relevance to anybody outside the artist’s family, immediate circle of friends or fellow servicemen. In such cases the art-works were made without any intention of their being passed on to anybody else.

A second reason for not identifying the maker of a work using spent ammunition was that technically ammunition, live or spent, remained the property of the New Zealand government. A serviceman could be charged with theft if he was found to be in possession of ammunition he had not been issued with. As in the First World War, the possibility that a man could be prosecuted for being in the possession of non-issue ammunition or shell casings was a strong disincentive for the artist to attach his name to his creations. My father was awarded ten days Field Punishment for being in possession of a 50 calibre bullet which he was delousing to make a model aircraft with on Stirling Island in 1943. He was even threatened with court-marshal for the offence. Although his diary does not reveal how he acquired the bullet, it was most likely a projectile from an aircraft machinegun, bartered or swapped with an American serviceman at the nearby airstrip.

Some of the men created souvenir pieces almost on a mass-production basis. A few made substantial amounts of money selling their wares. A thriving souvenir and craft-market was held quite regularly on the outskirts of Henderson Field where New Zealanders sold their produce to comparatively well-paid GI’s. When art-pieces were made for sale it was not usually seen as necessary to record the name of the creator. It was understood that the buyer was interested in purchasing a memento of his time in the Pacific. He was generally not so interested in knowing who was responsible for making it. A few of the more entrepreneurial servicemen made substantial amounts of money from their creations, one claiming he was able to purchase a vacant section for the construction of his first house on returning to New Zealand with his earnings.

For the above reasons there is often little or nothing to indicate where and when a work was made, let alone who made it. Family history and oral tradition can provide essential information, but when an art-work changes hands through being given away, sold, or other means, the provenance of the piece may be lost forever. In such cases there are sometimes indicators which can help us make informed guesses: the date, serial numbers, or other markings stamped on the base of an artillery shell that has been turned into an art work; stylistic references in the work itself (for example Art Nouveau designs were popular with World War 1 soldier/trench artists); aircraft types (especially the Japanese Zero and Lockheed P38 Lightning, which were common aircraft types in the Pacific, while the Spitfire related more to the European theatre) or other military equipment that may be specific to a time and place; photographs of individuals posing with an art work they have made; a soldier’s reference to creating a piece of art work in his war diary, or documentation sometimes attached to a work by a wife or acquaintance of the maker, often after the war was ended and the piece brought home.

Sometimes when a piece was created as a personal memento, the soldier-artist might engrave the name of his unit, places he had served and the place he was stationed during the time he made the work, and yet not include his own name. The example in Figure 4 was made by a man who belonged to the Royal New Zealand Artillery in Bougainville. That is all we know. In such cases, without other documentation, we are left knowing where and when a piece was made, but not who made it. Often even this basic information was excluded, with the design reduced to a generic depiction of coconut trees on an anonymous tropical beach (Figure 5).

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

Sometimes a Christian name was included, which rendered the item a little more personal and relevant to the family of the soldier, but which still protected the creator’s anonymity. The inclusion of family names soon became a common practice in other forms of soldier art as well. In the example shown here, the larger shell casings give the names of the Solomon and Treasury Islands, while the two smaller are dedicated to Roy and Nancy. Who were they? The serviceman and his wife, or their two children? It is likely we will never know. (Figure 6).

Depending on medium and intended usage, a degree of self imposed and/or official censorship could also be responsible for a lack of specific detail denoting places and dates. Nothing was permitted to be recorded which could benefit the enemy should a diary or sketchbook fall into enemy hands. (For this reason, servicemen were also generally not permitted their own cameras. The photographic records we have of the New Zealand involvement in the Pacific War were mostly taken by official photographers. There were no facilities for processing amateur photographers’ film anyway: no chemist shop to drop your film off at in Guadalcanal, and even the official photographers experienced problems preserving film-stock in the tropical heat and humidity.)

Establishing provenance can be even more difficult in the case of Navy art-works because the lifestyle of the sailor is generally more peripatetic than that of the soldier, or even the Air Force serviceman. Sailors frequently include the name of their ship along with the places they have visited on an art work, but inevitably naval ships change their station, and even their war theatre, more often than the other services do, often making it impossible to establish a location as part of the broader provenance of an art-piece.

Some of the earliest New Zealand Pacific War soldier art was produced in Fiji. New Zealand forces, which were to form the basis of the Third Division, were garrisoned there from 1940 until 1942 to oppose the Japanese threat, before being returned to New Zealand when the role of protecting Fiji and Tonga was taken over by the Americans. New Zealand soldier-art from the early period of the War in the Pacific, especially from Fiji, often included personalised dedications which bear poignant witness to the homesickness and sense of loss engendered by separation from family that these young men’s first (and often only) overseas experience produced, in an age when any form of travel was a major undertaking and far less common than it is today.

Many of the soldiers in Fiji were moved to create a talisman to mark their visit to what for most of them was an exotic and at the time very distant shore; a hand-crafted tortoiseshell badge with the “Onward New Zealand” logo and the name of the host country symbolised the most important aspects of what they hoped would be a brief visit. Decorative shields and badges made from tortoise shell or bone were very popular. Tortoise shell, coconut shell and sometimes animal bone appear to have popular choices of material for the soldiers in Fiji, because of availability and because it could be carved and polished relatively easily with the tools available to them. With their makers’ futures uncertain, these works commonly include sentimentalised references to “Mother”, “Mum and Dad”, or even an exhortation to simply “Be Happy” (Figures 7 – 9).

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

The “Onward New Zealand” motif was a popular motif amongst servicemen, especially those garrisoned on Fiji in the early stages of the war, and variations were made in a wide range of materials, including animal bone (Figure 11). The distinctive motto can be traced to the British Section of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) in World War 1. It was formed by New Zealanders who lived in England who enlisted with the NZ Army in the UK and was based on the motto of the of the 1911 New Zealand Coat of Arms (Figure 12).

The unit, with a strength of 7 officers and 233 men, was possibly the shortest lived military unit of all time. The unit sailed for Egypt on 12 December 1914 and was dissolved the following day. The servicemen were absorbed into the New Zealand Army Service Corps and an Engineer Field Company. However their “Onward” hat and collar badge design went on to become the general service badge of the (WW1) NZEF and (WW2) 2NZEF as well as 3 Division in the Pacific. Originally these badges were made with an oak leaf wreath but this was later replaced by the more familiar (and appropriate) fern leaf motif.

- Figure 11

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

The photograph of the carved coconut shells was discovered by collector John Perry being used as a backing board for another framed art-work (Figure 13). There was no record of who had made them or where they were made, but it is possible in such situations to make a few guesses. Clearly the artworks originated in the Pacific; linking the material it is made from and the type of imagery, it is possible to conjecture that these art-pieces were made by a New Zealand soldier in Fiji, but with the original pieces most likely lost, and no information attached to the photograph, we will probably never know for sure. One wonders where these beautiful handcrafted objects are now, or whether they even still exist. It is sobering to contemplate that this photograph, itself rescued from potential oblivion by chance, may be the only record of it, the name of its creator most likely already lost to posterity.

A modern phenomenon which compounds the difficulties of keeping track of the creators of war art (which is not unique to New Zealand), is the practice of families passing unsigned and undocumented artworks from one generation to the next.

Often this results in collections of work being split up as they get divided amongst second or third generation family-members. Sometimes the younger family members are not interested in keeping the works and they are sold to collectors or dealers, or are simply offered for sale through on-line auction websites such as ebay, or its New Zealand equivalent, Trade-Me (Figure 13).

This trend will inevitably increase as the demand for World War 2 soldier art drives the monetary value of the objects higher and the temptation to convert them into cash increases. Unfortunately the provenance of these art works – who made them and what were the circumstances of their making – takes second place and is frequently lost. In such cases all we are left with are the objects themselves. To lose or destroy the provenance of an artwork, the identity of the soldier and the circumstances behind it’s making, especially with regard to one who gave his life in the fighting, has been compared to killing its creator twice.

Museums such as the Auckland War Memorial Museum, The New Zealand Navy Museum in Auckland, The New Zealand Army Museum at Waiouru, and the Air Force Museum in Christchurch as well as many private collections around the country, have a crucial role in preserving the identity and war experiences of our servicemen and women through the protection and preservation of New Zealand soldier art and the identities and histories of those who created it.